witch hunt

The phrase witch hunt is surprisingly recent. One might expect it to date to the seventeenth century, when real hunts for supposed witches were rampant across Europe. But its use in relation to witches only dates to the late nineteenth century and its political use only to the twentieth. And until the mid twentieth century, whether the context was witches or some other undesirable person, witch hunt was almost always applied to the persecution of marginalized groups by those in power. But starting around 1960, the term began to be used by those in power in reference to criticism of themselves and their policies.

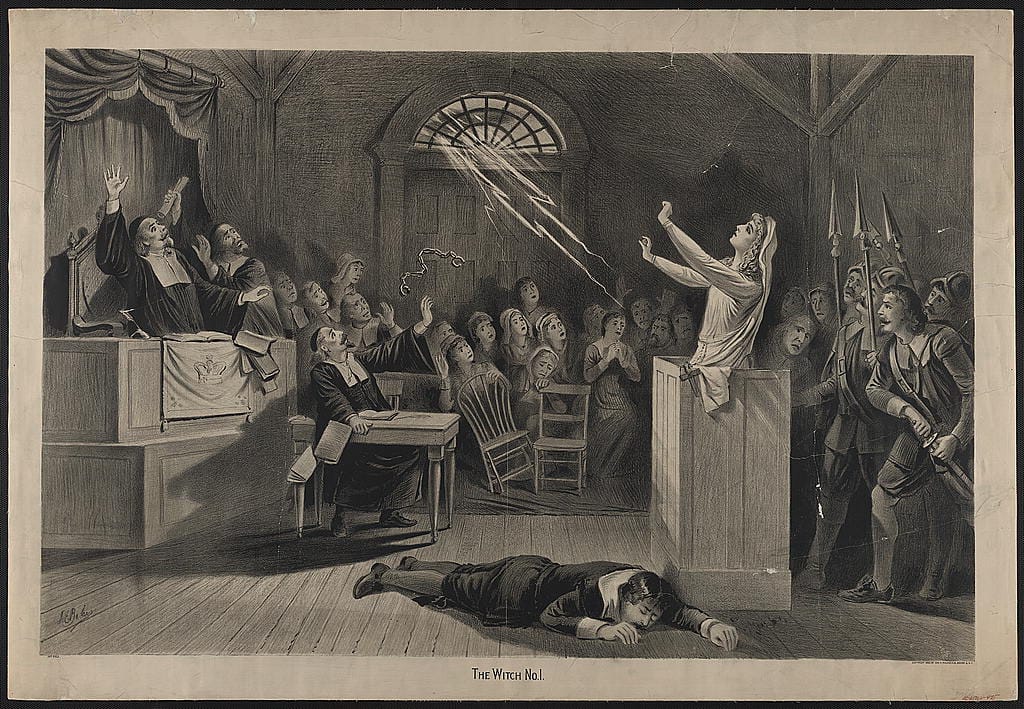

The earliest use of witch hunt that I’m aware of is a literal reference to supposed witches in the seventeenth century, but it doesn’t appear until the mid nineteenth. The following account of the infamous Salem witch trials of 1692–93 appears in “Bancroft’s History of the United States,” published in the magazine De Bow’s Review of August 1853. While it is about supposed witches, the description of the zeal and tactics of the persecutors accords with those of the modern political sense:

Some strange cases of convulsions occurred at the village of Danvers, in the family of Parris the minister. Parris had just been engaged in a violent quarrel with some of his flock, and he seized upon this glorious opportunity for revenge. From members of his own family, by instructing and prompting, he obtained the names of those who had bewitched them, and these answers were given as evidence in the court of justice. Against his enemies he employed all the efforts of his malicious and revengeful spirit. But Parris did not do his work of infamy alone. It was too inviting a subject for the ministers of Boston not to participate in, and with Cotton Mather at their head, they eagerly joined in the grand witch hunt. Witch-finding was made a science. Honest bigotry and malicious craft kept up and increased the excitement. Every one who was bold enough to express his disbelief in witchcraft, and his belief in the rascality of the whole business, was a doomed man. Evidence tending to convict their friends was suppressed, and evidence tending to convict their enemies was manufactured. But the holy zeal of the ministers was not satisfied with the judicial murder of those of their flocks who had incurred their displeasure. It was next directed against those of their own order, who had the intelligence and the honest courage to oppose this disgraceful affair.

The earliest figurative and political use of witch hunt I can find of the term is from 1900 in the context of Canadian politics. In a pair of articles, again in the Manchester Guardian, on the Canadian federal election of that year, reporter Harold Spender wrote on 30 October 1900:

For four years there has been absolute peace between the races and religions of this strangely mingled half-continent. For four years; but now I fear that the mischievous race-suspicions of South Africa are already spreading here, and that the pernicious spirit of the witch-hunt is already appearing in the speeches and writings of this campaign.

[…]

But more serious for the moment is the loyalist witch-hunt. You would imagine that Englishmen would be content with the proud consciousness of these people’s [i.e., French Canadians’] allegiance, that they would recognise that such allegiance, so given, demands in return some delicacy and generosity in the recipient. But no; they must peep and pry down the mouth of the gift-horse, and then, when the teeth snap in angry resentment, there is a howl of dismay and shallow indignation.

And on the next day, Spender wrote:

Well, that was the sort of attack Mr. Tarte had to meet—an attack which would, in the zeal of a witch-hunt, turn these innocent sayings into treasonable utterances.

Within two decades the term began to be used in the United States, first in the context of the Red Scare following the Russian Revolution. From the Chicago Daily Tribune of 8 March 1919:

Col. Raymond Robins of Chicago, former head of the American Red Cross mission in Russia, warned the senate propaganda investigating committee today that no headway would be made in trying to check bolshevism by “witch hunt” methods.

The use of witch hunt in American politics spiked again in the 1950s with McCarthyism and the hearings of the House Un-American Activities Committee, and the context was most often that of persecuting those on the political left by those in power.

The OED first records the use of witch hunt to refer to political attacks on government officials in a 29 January 1960 Daily Telegraph article about alleged corruption by British Transportation Minister Ernest Marples, a case of a government official being investigated by the opposition minority:

NO WITCH-HUNT

Labour Leaders’ Attitude

Our Political Correspondent writes: The Opposition Front Bench do not intend to conduct a “witch-hunt” against Mr. Marples over his business connections. But this is no guarantee that back-benchers will not seek to pursue the matter further.

If there is any disposition to criticise Mr. Marples, it will be on the ground that he might have taken steps to get rid of his shares when he became Postmaster-General, rather than wait until he was appointed Minister of Transport.

And, of course, no article on witch hunt could go without referring to Donald Trump, who has elevated this particular sense to new heights. According to the Trump Twitter Archive, a site that is no longer online, Trump had tweeted witch hunt 190 times between his first inauguration and 1 May 2019. For an example that falls outside that date range, on 17 October 2019, Trump tweeted in about the first effort to impeach him:

The Greatest Witch Hunt in American History!

That’s a far cry from the persecution of seventeenth-century women who did not conform to society’s ideas of how they should act.

Sources:

“Bancroft’s History of the United States.” De Bow’s Review, 15.2, August 1853, 160–86 at 179–80. HathiTrust Digital Library.

“No Witch-Hunt.” Daily Telegraph (London), 29 January 1960, 1/2. Gale Primary Sources: Telegraph Historical Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary Online, September 2021, s. v. witch hunt, n., witch-hunt, v.

Spender, Harold. “The Canadian Elections” (30 October 1900). Manchester Guardian (England), 9 November 1900, 10/3. ProQuest Newspapers.

———. “The Canadian Elections” (31 October 1900). Manchester Guardian (England), 15 November 1900, 10/2. ProQuest Newspapers.

Trump, Donald J. (@realDonaldTrump), Twitter.com (now X.com), 17 October 2019.

“Warns America to Use Care in Fighting Reds” (7 March 1919). Chicago Daily Tribune, 8 March 1919, 2/2. ProQuest Newspapers.

Image credit: Joseph E. Baker, c. 1892, George H. Walker & Co. Library of Congress. Public domain image.