waive / waif / wave / waver

Waive, waif, wave, and waver all appear to be related, and while they may share a common Proto-Germanic root in *webna- / *wepna-, their etymological histories are quite different.

The verb to waive, comes from the Anglo-Norman legal verb weyver, meaning to dismiss a legal obligation. English use dates to the late fourteenth century, but in a more general sense of to abandon or give up something. We see it in Chaucer’s Second Nun’s Tale, where Saint Cecilia pledges to God her virginity:

The palm of martirdom for to receyve,

Seinte Cecile, fulfild of Goddes yifte,

The world and eek hire chambre gan she weyve.

(In order to receive the palm of martyrdom,

Saint Cecilia, filled with God’s gift,

The world and also her bed-chamber did she waive.)

The legal sense of dismissing an obligation in English dates to the mid fifteenth century. Although the legal sense is the original sense in Anglo-Norman, it appears later in English because most legal writing prior to the fifteenth century would have been in French or Latin.

Waif, which we see today mostly in the sense of an orphaned child, comes from a similar concept of abandonment. The Middle English weif, from the Anglo-Norman waif, meant ownerless livestock or other property, property that was therefore liable to seizure by the authorities. The word starts appearing in English writing, mostly legal documents and inventories, starting in the early thirteenth century.

By the seventeenth century, waif was being used more generally to refer to a person or thing that has been abandoned or neglected. In his 1624 Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions, John Donne writes:

But what a wretched, and disconsolate Hermitage is that House, which is not visited by thee, and what a Wayue, and Stray is that Man, that hath not thy Markes vpon him?

And in the late eighteenth century, waif could refer to a “fallen” woman, an adultress or prostitute. William Cowper does so in his 1785 poem The Task:

And she that had renounced

Her sex’s honor, was renounced herself

By all that priz’d it; not for prud’ry’s sake,

But dignity’s, resentful of the wrong.

’Twas hard perhaps on here and there a waif

Desirous to return and not received,

But was an wholesome rigor in the main,

And taught th’ unblemish’d to preserve with care

That purity, whose loss was loss of all.

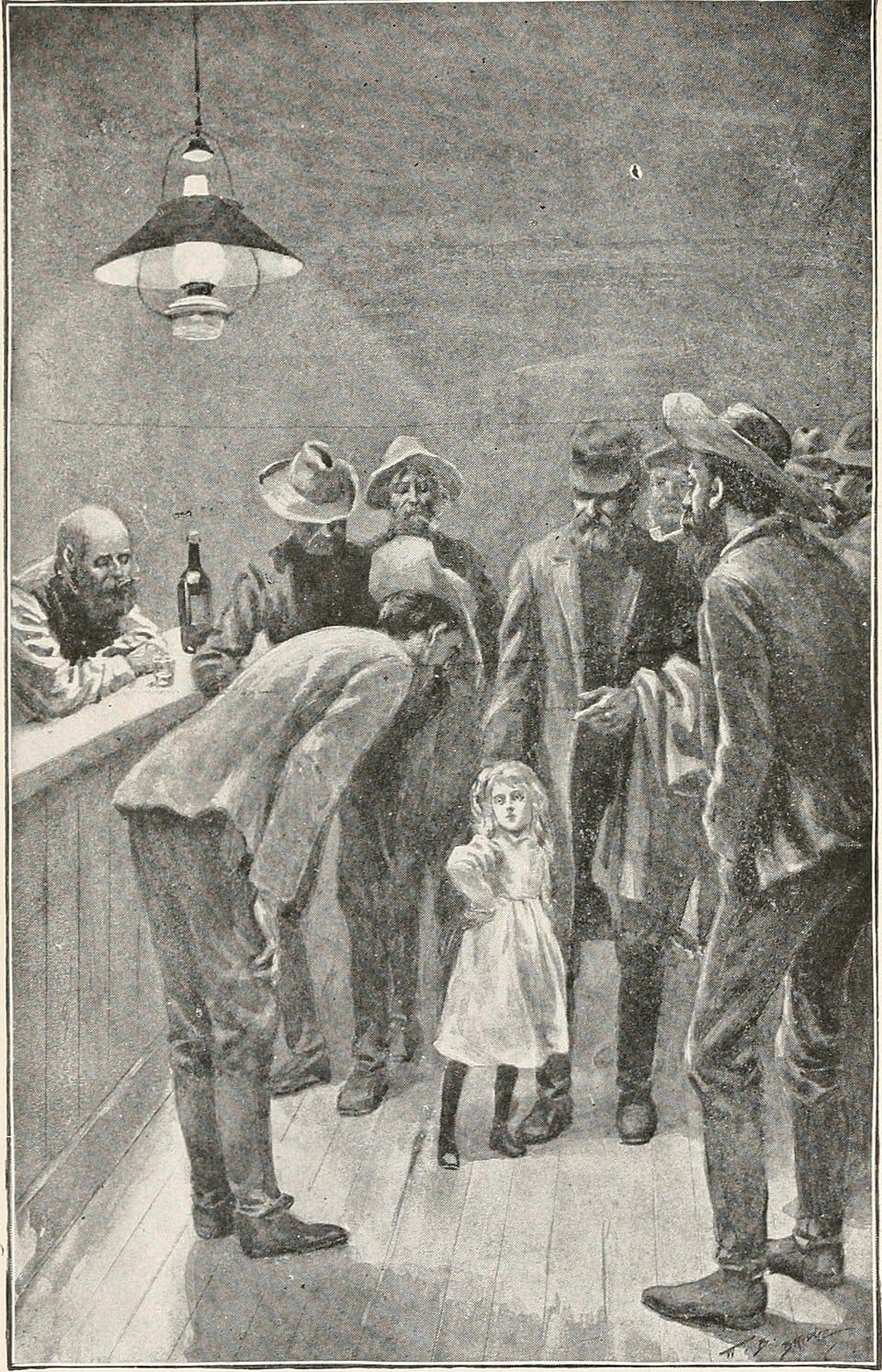

A century later, the word had acquired the sense we know today, that of an orphaned or neglected child. From Godfrey Pike’s 1875 Children Reclaimed for Life about the children living on London’s streets:

Many of these narratives, picked up in the street, have been issued in separate tracts and leaflets, to effect a good purpose by attracting public attention to the woes of London waifs and strays. It is proper that the public should learn something about these children.

So while waive and waif are linked by a sense of abandonment, wave and waver come into our language by a different route.

The verb to wave comes from the Old English verb wafian. We see the verb in Ælfric’s Exaltation of the Holy Cross, written around the turn of the tenth century:

Þeah þe man wafige wundorlice mid handa,

ne bið hit þeah bletsung buta he wyrce tacn

þære halgan rode, and se reða feond

biþ sona afyrht for ðam sigefæstan tacne.

(Though someone may wave their hands wondrously, it is not a blessing unless he makes the sign of the holy cross, and the cruel fiend will immediately be frightened by that victorious sign.)

Waver comes from a related Old English word, wæfre. We find this one in Beowulf, in the Finnsburg episode:

Swylce ferhðfrecan Fin eft begeat

sweordbealo sliðen æt his selfes ham,

siþðen grimne gripe Guðlaf on Oslaf

æfter sæsiðe sorge mændon,

ætwiton weana dæl; ne meahte wæfre mod

forhabban in hreþre.

(Likewise, cruel sword-death also took the bold in spirit Finn at his own home, after Guthlaf and Oslaf spoke of the grim grip of sorrow after the sea-voyage, and laid blame for their share of troubles; a wavering heart could not be restrained in the breast.)

So while the pairs waive/waif and wave/waver are probably connected by a common root back in the mists of time, their development since the language has been written has been quite different.

Sources:

Ælfric. “Exaltation of Holy Cross.” In Mary Clayton and Juliet Mullins, eds. Old English Lives of the Saints, vol. 3 of 3. Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 60. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2019, lines 151–54, 34.

Anglo-Norman Dictionary, AND2 Phase 6, 2022–25, s.v. waiver, v., waif, n.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. “The Second Nun’s Tale” (c. 1380). The Canterbury Tales, lines 8:274–76. Harvard’s Geoffrey Chaucer Website.

Cowper, William. The Task. London: J. Johnson, 1785, 95. Gale Primary Sources: Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

Donne, John. Devotions Vpon Emergent Occasions. London: Thomas Jones, 1624, 329. ProQuest: Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic Online, 2009, s.v. *webna- ~ *wepna-. Brill: Indo-European Etymological Dictionaries Online.

Fulk, R. D., Robert E. Bjork, and John D. Niles, eds. Klaeber’s Beowulf, fourth edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008, lines 1146–49a, 40.

Middle English Dictionary, 4 March 2025, s.v. weiven, v.1, weif, n.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. waive, v.1, waif, n., wave, v., waver, n.

Pike, Godfrey Holden. Children Reclaimed for Life. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1875, 81. Archive.org.

Image credit: Unknown artist, 1900. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.