virus / viral

Virus is a word that has evolved alongside the evolution in medical knowledge; before the twentieth century a virus was something quite different from the microorganisms we assign the name to today, and even more recently the word has broken the bounds of biology and infected the realm of silicon and circuits.

Virus is from Latin, where the word means poison, venom, or a bodily discharge such as pus or semen. In classical Latin it only referred to animal semen but was extended to human semen in medieval Latin. Because of this last meaning, it’s tempting to associate the word with vir, meaning man and the source of the English word virile, but it appears as if the root of virus is quite different, and there are apparently no Latin uses of virus to refer to human semen. The Latin vir comes from the Proto Indo-European root *wiro-, associated with masculinity and giving rise to other words such as violence and virtue, while most scholars contend that the Latin virus comes from the PIE root *wiss-, associated with poison. (A minority view holds that it comes from *weis-, with a meaning of to flow and also giving us words like viscous.)

The word makes its English debut toward the end of the fourteenth century. It appears in John Trevisa’s translation of Bartholomæus Anglicus’s De proprietatibus rerum (On the Properites of Things) where, citing Isidore of Seville's Etymologiae, it associates virus, in the human semen sense, with the Latin vir, man:

Among the genitals on hatte þe pyntyl, veretrum in latyn, for it is a man his owne membre oþir for it is shamefast membre oþir for virus come ouȝt þerof. For propirliche to speke, þe humour þat comeþ out of mankynde hatte virus. So seiþ Isidre.

(Among the genitals, the penis is called veretrum in Latin, for it a man’s own member, first because it is a shameful member, second because virus comes out of it. To speak correctly, the humor that comes out of mankind is called virus. So says Isidore.)

Around the same time, virus appears in the sense of pus or discharge from a wound in a translation of Lanfranc of Milan’s treatise on surgery:

If þe vlcus be virulent, þat is to seie venemi [. . .] If þe virus be wiþoute heete & þe membre haue noon heete, waische it wiþ watir.

(If the ulcer is virulent, that is to say with venom [. . .] If the virus is without heat and the limb has no heat, wash it with water.)

A couple of centuries later the Latin sense of virus as poison entered English usage. This use appears in a figurative sense in the 1599 publication of Master Broughton’s Letters:

In an epistle to the Lord Treasurer, you will put his Graces fame in print: in your letters to D. Stoll. you will set his Graces fame past cure: in priuate letters to himselfe, belching out vnsauourie menaces of that, which here you haue disgorged. Wherein you haue spent all the vires and power you haue for the defence of a vaine paradox, and spit out all the virus and poyson you could conceiue, in the abuse of his reuerend person.

And the virus-as-poison sense can still be found in current usage, as this 1988 citation from the Chronicle-Telegram of Elyria, Ohio shows:

Farmers cut the legs off woolen stockings to wear on wrists and forearms, for the virus of a snake bite would be absorbed by the woolen yarn, minimizing the danger of infection.

The modern biological sense of virus as a microscopic pathogen appears in 1900. From the Journal of Comparative Pathology and Therapeutics of that year:

Thanks to the researches of Löffler, we also know that the virus of foot-and-mouth disease passes through a Berkefeld filter when it is suspended in a watery liquid, but it is arrested by such a filter from an albuminous liquid, and, presumably on account of its small size, it has not yet been made visible to the human eye.

As this citation shows, viruses were originally distinguished from bacteria and other microorganisms by their size. Filters could trap bacteria, but viruses were small enough to pass through them. As a result, many very small microorganisms were originally classified as viruses, although we wouldn’t do so today. Today, a virus is a DNA or RNA molecule surrounded by a protein coat that can only exhibit biological functions inside a host cell. Alexander Nelson’s 1946 Principles of Agricultural Botany exhibits this modern understanding of what a virus is:

Some viruses have been isolated from the host, and all have proved to be some form of nucleic acid; they are of the nature of nucleo-proteins.

And even more recently, a new type of virus has been envisioned, the computer virus, appearing first in fictional accounts of future technologies. Science fiction often invents technologies that only later become a reality. Jules Verne anticipated the submarine and scuba gear in his 1869 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, and H. G. Wells wrote about atomic bombs in 1914. Computer viruses are another technology that first appears in fiction. The first known reference to a computer virus is in David Gerrold’s novel 1972 novel When Harlie Was One. Gerrold specifically modeled the concept on pathogenic biological viruses:

“Do you remember the VIRUS program?”

“Vaguely. Wasn’t it some kind of computer disease or malfunction?”

“Disease is closer. There was a science-fiction writer once who wrote a story about it—but the thing had been around a long time before that. It was a program that—well, you know what a virus is, don’t you? It’s pure DNA, a piece of renegade genetic information. It infects a normal cell and forces it to produce more viruses—viral DNA chains—instead of its normal protein. Well, the VIRUS program does the same thing.”

“Huh?”

Handley raised both hands, as if to erase his last paragraph. “Let me put it another way. You have a computer with an auto-dial phone link. You put the VIRUS program into it and it starts dialing phone numbers at random until it connects to another computer with an auto-dial. The VIRUS program then injects itself into the new computer. Or rather, it reprograms the new computer with a VIRUS program of its own and erases itself from the first computer. The second machine then begins to dial phone numbers at random until it connects with a third machine. You get the picture?”

[. . .]

“You could set the VIRUS program to alter information in another computer, falsify it according to your direction, or just scramble it at random, if you wanted to sabotage some other company.”

Gerrold’s VIRUS was a specific program with that name (he also envisioned an anti-virus program called VACCINE), but it wasn’t long before other writers had picked up the idea. John Brunner’s 1975 science fiction classic The Shockwave Rider features computer viruses and coins the use of worm in relation to such programs:

If I’d had to tackle the job, back when they first tied the home-phone service into the net, I’d have written the worm as an explosive scrambler, probably about half a million bits long, with a backup virus facility and a last-ditch infinitely replicating tail.

And from the June 1982 issue (#158) of the comic Uncanny X-Men:

We simply design an open-ended virus program to erase any and all references to the X-Men and plug it into a central federal data bank. From there, it’ll infect the entire system in no time.

But by the time that X-Men comic hit the newsstands, the first real computer virus was already in existence. A ninth-grader in Mt. Lebanon, Pennsylvania wrote the “Elk Cloner” virus in 1981, that spread among Apple II computers via infected floppy disks. By modern standards, Elk Cloner was pretty harmless, although it was persistent and was still being spotted a decade later. It wasn’t until 1984 that computer scientists started publishing papers using the term virus.

The adjective viral makes its debut in 1948, originally restricted to characterizations of the biological entity. But like the move to computers, the adjective has infected another domain, that of marketing. Viral marketing appears in 1989, referring to word-of-mouth advertising. From the magazine PC User of 27 September 1989:

At Ernst & Whinney, when Macgregor initially put Macintosh SEs up against a set of Compaqs, the staff almost unanimously voted with their feet as long waiting lists developed for use of the Macintoshes. The Compaqs were all but idle. John Bownes of City Bank confirmed this. “It's viral marketing. You get one or two in and they spread throughout the company.”

The advent of public access to the internet meant that viral marketing itself could go viral. From the New York Times of 30 August 2001:

Many of the new games are viral, meaning that they permit players to spread the games by e-mail to friends.

And from a 2004 essay by Andrew Boyd that uses go viral to refer to the initial efforts of the political group MoveOn.org:

MoveOn itself was founded well before the war, or even Bush’s presidency, as an effort during Bill Clinton’s impeachment to push Congress to censure the president and “move on.” Their petition also went viral, gathering half a million signatures in a few weeks. After that, the group used its list to raise money for progressive Democrats. By the time Bush was threatening war, MoveOn had become a well-oiled machine.

So virus and viral have gone from poisonous slime to internet meme in just six centuries.

Sources:

American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots, third edition, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011, s.v. weis-. wiro-.

Bartholomæus Anglicus. On the Properties of Things (De proprietatibus rerum) (before 13998), vol. 1 of 3. John Trevisa, trans. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975, Book 5, Chap. 48, 1.261.

Boyd, Andrew. “How a Twenty-Year-Old Revolutionized the Internet.” In Adrienne Maree Brown and William Upski Wimsatt. How to Get Stupid White Men Out of Office. Brooklyn: Soft Skull Press, 2004, 167–72 at 168

Brunner, John. The Shockwave Rider. New York: Harper & Row, 1975, 176. Archive.org.

Carrigan, Tim. “New Apples Tempt Business.” PC User, 27 September 1989. Quoted at Wordspy.com.

Davis, Connie. “Murray Ridge Road Once Swamped with Forests.” Chronicle-Telegram (Elyria, Ohio), 13 September 1988, A-11/3. NewspaperArchive.com.

von Fleischhacker, Robert, ed. Lanfrank’s “Science of Cirugie.” Early English Text Society. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1894, 80. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Gerrold, David. When Harlie Was One. New York: Ballantine, 1972. Archive.org.

Latham, Ronald E., David R. Howlett, and Richard K. Ashdowne. Dictionary of Medieval Latin form British Sources. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2013, s.v. virus, n.

Lewis, Charlton T. and Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1879, s.v. virus, n. Brepols: Database of Latin Dictionaries.

M’Fadyean, J. “African Horse-Sickness.” Journal of Comparative Pathology and Therapeutics, 13.1, 31 March 1900, 1–20 at 16. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Mallory, J. P. and D. Q. Adams. The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006, 261, 263.

Marriot, Michael. “Playing with Consumers.” New York Times, 30 August 2001, G1/3. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Master Brovghtons Letters. London: John Wolfe, 1599, 14. ProQuest: Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Middle English Dictionary, 8 February 2025, s.v. virus, n.

Nelson, Alexander. Principles of Agricultural Botany. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1946, 464. Archive.org.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2008, s.v. virus, n.; 2005, viral, adj.

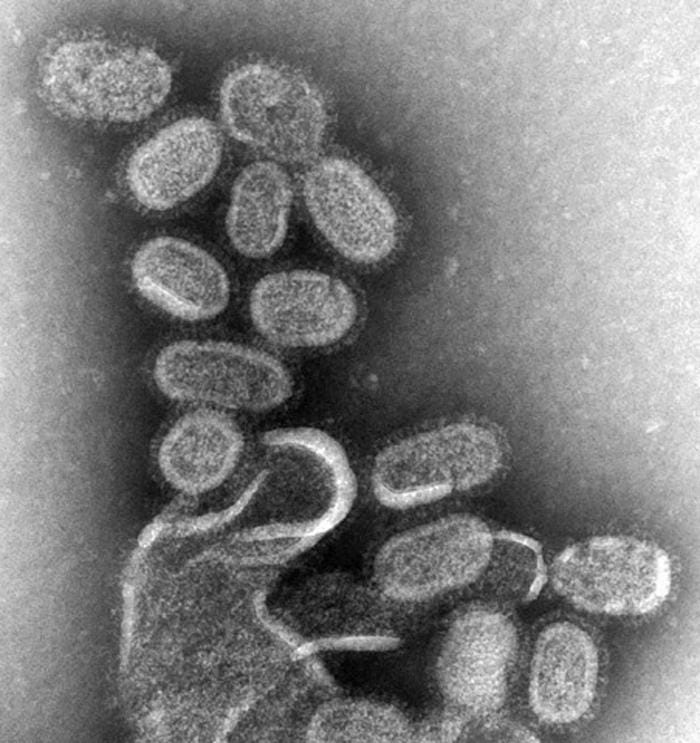

Photo credit: Cynthia Goldsmith, 2005. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.