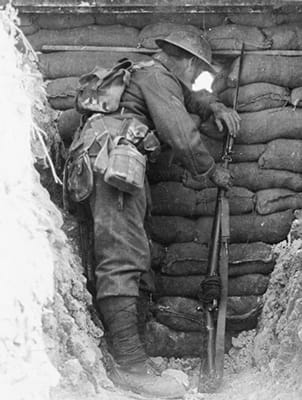

Tommy / Tommy Atkins

30 January 2026

The great joy of running this website is that now and again I uncover an origin that simultaneously connects with great historical figures and events and reveals how language, the most human of inventions, works. The British slang term for a soldier, Tommy, is just such a word. It is short for Tommy Atkins, and the word’s history, both purported and real, pulls in both the great, i.e., the Duke of Wellington, and the small, i.e., an example of how to fill out a government form correctly.

As mentioned, Tommy is slang for a British private soldier. It is famously used in an 1890 Rudyard Kipling poem of that title, although that is hardly the first use of the term:

I went into a public-’ouse to get a pint o’ beer,

The publican ’e up and sez, “We serve no red-coats here.”

The girls be’ind the bar they laughed an’ giggled fit to die,

I outs into the street again an’ to myself sez I:

O it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an’ “Tommy go away”;

But it’s “Thank you, Mister Atkins,” when the band begins to play,

The band begins to play, my boys, the band begins to play,

But it’s “Thank you, Mister Atkins,” when the band begins to play,

Today, the word is chiefly associated with those who fought in the First World War—the British equivalent of the American doughboy—but its origins are at least a hundred years older, dating to the Napoleonic wars, if not before. It’s primarily found in British usage, but North Americans may be familiar with Tommy from movies about the two World Wars and from the Kipling poem. And the oldest among us will remember its use during the first half of the twentieth century, when the word had some currency on this side of the pond.

Who is the Tommy Atkins who lent his name as a sobriquet for the British soldier? Most likely there is no real person behind the term’s use. While there have been a number of British soldiers with that name over the centuries, the name was probably picked because its only remarkable feature is its lack of remarkability, like John Smith. The first securely documented use of the term is in the form Thomas Atkins. And not only is it in that form, it’s quite literally on a form, the 1815 Collection of Orders, Regulations, &c., a book that was issued to every British soldier and that contained a record of his pay and allowances. Like all good bureaucratic documents, that book provides an example of how to properly fill out a form for a soldier’s pay:

Description, Service, &c. of Thomas Atkins, Private, No. 6 Troop, 6th Regt. of Dragoons. Where Born… Parish of Odiham, Hants.

When ditto… 1st January 1784.

Height… 5 Feet 8½ inches.

[...]

Bounty, £7, 7s. Received, Thomas Atkins, his X mark.

The beauty of this specific use is that it would have been seen by thousands of officers and soldiers all across the British Empire, permanently cementing the name’s use as a soldier’s sobriquet. In fact, this book was so closely associated with the name that soldiers took to calling the book itself the Tommy Atkins. We tend to look to Shakespeare and great literary works for linguistic innovation, but more often it’s things like humble bureaucratic documents, texts that we see on a daily basis but don’t take conscious note of, that leave a more profound mark on the language.

There is a popular story that the name in the 1815 document was coined by the Duke of Wellington in honor of a soldier who had died bravely at the Battle of Boxtel in 1794, Wellington’s first major battle. The story, which is unsupported by any evidence other than repeated hearsay claims that it is true, says that the war office consulted the duke on an appropriate name for a soldier to use in its 1815 pay book and that Wellington recalled the battle where Atkins, as he lay dying, told the young duke-to-be that the multiple wounds he had received were “all a day’s work.” Wellington allegedly chose the name to honor the brave lad. In addition to these alleged last words being too good to be true, the biographical details in the pay book don’t match those of the alleged namesake, and most tellingly, it is unlikely that the War Office would have bothered Wellington with such bureaucratic minutiae in 1815, given that the duke was busy with other things at the time, such minor concerns as the Battle of Waterloo and exiling Napoleon to St. Helena.

If this tale has no evidence behind it, what evidence would it take to convince us that it were true? Well, if someone produced a draft manuscript of the 1815 pay book with Wellington’s emendation or a letter from the Duke instructing the change be made, that would clinch it. Failing that, an after-the-fact letter or memoir of Wellington’s telling the story of his directing the change would be almost as good. A documented, second-hand account by someone who knew Wellington would be strong evidence, but not in-and-of-itself convincing. Even evidence from muster rolls that a soldier named Thomas Atkins of the 33rd Regiment of Foot (Wellington’s regiment) died at Boxtel would be something. But we have none of these or anything like them.

Furthermore, the Wellington story doesn’t appear until many decades after the fact—the earliest version I know of that connects Wellington to Tommy Atkins only dates to 1908, and that one that is demonstrably false because it gives the date of Wellington’s coinage as 1843. I have found no versions of the tale, even those told by professional historians, that reference any source material that would support the tale as being true. The tale is simply repeated and everyone, even historians who should know better, take that repetition as evidence. If the Iron Duke ever related the Atkins story to someone, we have no record of him doing so. More likely this is another example of a famous name over time becoming associated with a myth. We have a tendency to ascribe events and phenomenon to famous people.

There is a possible older use of Tommy Atkins to refer to generic British soldiers from 1743, although the evidence for this appearance is only in secondary sources. On 24 December 1937, the Daily Telegraph, which had been publishing an ongoing series of reader commentaries on the origin of the term, published this letter:

Sir—In reference to the interesting discussion in your columns concerning the genesis of the term “Thomas Atkins” as generally applied to the British soldier, it would appear that the appellation had its origin long before the period attributed to Wellington.

This is evidence from a M.S. letter in my possession, dated 1743, and addressed from Jamaica, in which the writer, an Anglo-Irish officer, after giving a vivid and thrilling description of a mutiny among the hired soldiery, says: “… Except for those from N. America (mostly Irish Papists), ye Marines and Tommy Atkins behaved splendidly…”

So much for the modern habit of dogmatic finality on the part of our would-be historians.—Faithfully yours,

EDW. E. BURGESS, F.R.S.A.

Granton-road, Leeds. Dec. 22.

If the manuscript letter is genuine, this would push the date of the term to the first half of the eighteenth century. That is certainly plausible, but all we have is this account of the letter from 1937. But even if the 1743 letter isn't genuine, it is likely that by the time the 1815 document was issued Thomas (or Tommy) Atkins was already a generic slang term for a soldier, and its appearance in the 1815 document is an attestation, rather than a coinage.

Perhaps it is fitting that the archetype of the British soldier be named for someone who exists only in myth.

Sources:

Burgess, Edward E. “Tommy Atkins in 1743” (letter, 22 December 1937). Daily Telegraph and Morning Post (London), 24 December 1937, 9/2. Gale Primary Sources: The Telegraph.

Carter, Philip. “Atkins, Thomas (d. 1794),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, online ed, May 2006.

Clode, Charles M. The Military Forces of the Crown: Their Administration and Government, vol 2 of 2. London: John Murray, 1869. 59. HathiTrust Digital Library.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, accessed 12 December 2025, s.v. Tommy Atkins, n.

Kipling, Rudyard. “Barrack-Room Ballads. II—‘Tommy.’” Scots Observer, 1 March 1890, 409–10 at 409/2. British Newspaper Archive.

Laffin, John. Tommy Atkins: The Story of the English Soldier. London: Cassell, 1966. xi–xiii. Archive.org.

Oxford English Dictionary Online, June 2014, s.v. Thomas Atkins, n., Tommy Atkins, n.; January 2018, s.v. Tommy, n.1.

Photo credit: John Warwick Brooke, 1916. Imperial War Museum. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.