tarheel / rosin heel

Tarheel is a nickname for a native of North Carolina. The term is preceded by the older rosin heel. Originally an epithet, its early history is mixed up in the racist attitudes of the antebellum South. But tarheel has been ameliorated and is now used proudly by residents of that state, and its use today is free of any racial connotation.

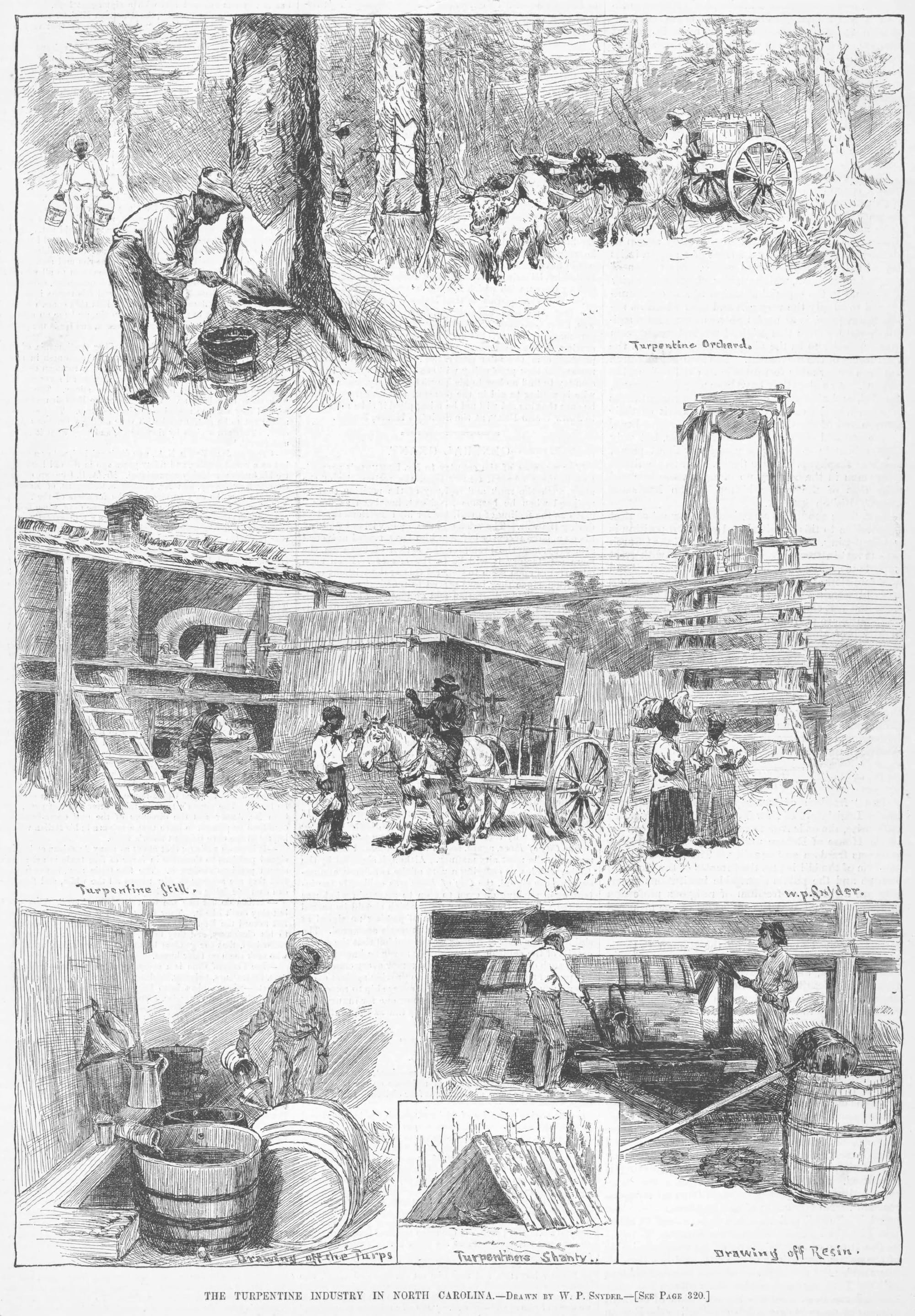

The tar and rosin in the term is from the use of pine-tree sap in the maritime and naval industries of the early nineteenth century. Workers who harvested the sap in the American South, a mix of poor whites and enslaved Blacks, would often go barefoot, getting the tar/rosin on the soles of their feet. And this industry was a significant contributor to North Carolina’s economy in the antebellum era.

The earliest use of rosin heel that I’m aware of is from a 5 May 1826 letter to the Natchez, Mississippi Ariel describing an argument between to white men, one well to do and the other poor:

One of the disputants was a short, fat, rich, independent looking fellow, with a large gold watch-key and chain, hanging from his fob, and a gold headed cane dangling in his right hand, and as I have since understood is a rich planter in this neighborhood; he most uncivilly told the other he had no right to an opinion upon the subject of a lighthouse; that he was a rosin heel, and should not offer an opinion upon a subject of national concern. The other who was dressed in plain homespun, with a long ox-whip in his hand, replied by calling the other a gum head, and told him he reckoned he had seen some people with golden purses have very gummy heads; that it was not every man who had a long purse that had a long head.

Note that gum is another name or pine-tree sap.

Also from 1826 is this from Timothy Flint’s account of his travels through the Mississippi Valley:

Such is the general face of the country in West Florida. It possesses in its swamps a considerable quantity of live oak, and masts and spars enough for all the navies of the world. It is capable of furnishing inexhaustible supplies of pitch, tar, &c. The high grass, which grows every where among the pine trees, opens an immense range for cattle. There are some tolerable tracts of land along the rivers; but generally the land is low, swampy, and extremely poor. The people, too, are poor and indolent, devoted to raising cattle, hunting, and drinking whiskey. They are a wild race, with but little order or morals among them; they are generally denominated “Bogues,” and call themselves “rosin heels.” The chief town is Pensacola, which grew rapidly, and received an increase of many inhabitants and handsome houses, until the fatal summer of 1822, when it suffered so severely from yellow fever, since which it has declined. It has a fine harbour, and the government has made it a naval depot, which will probably raise it once more.

Rosin heel seems to have been applied only to poor whites. Tarheel, however, was applied to both whites and Blacks. The difference may have to do with the fact that rosin is lighter than tar. Use of tarheel to refer to Blacks was probably influenced by the phrase, current at the time, like tar on a n——r’s heel. Here is an example of the phrase from Indiana’s Fort Wayne Sentinel of 16 September 1848. The article, in the dialectal voice of one Hetty Jones, undoubtedly fictional and perhaps Black, uses the phrase in reference to Martin Van Buren. During his earlier term as president, Van Buren, a Democrat, compromised his anti-slavery principles in order to get elected. In 1848 he was running on the abolitionist Free Soil Party ticket:

He talked as nice and soft as a Congressman about the dear people, and comperises of the constitution, and scrub treasury, & all them things—he stuck up to the South then like the tar to a n[——]er’s heel—woul n’t even let a woolly headed cuss go free in the District of Columbia—nor he wouldn’t let a dockiment of the abolitioners go in the mail bags.

The earliest published use of tarheel that I’m aware of, however, is in reference to poor whites. From a letter, dated 6 October 1846, published it the Emancipator, it is not specific to North Carolina:

There are at this moment at least as many poor whites in the slave states as there are slaves, who are hardly less miserable than the slaves themselves. They have no weight in society, grow up in ignorance, are not permitted to vote and are tolerated as an evil, of which the slaveholder would gladly be rid. They are never spoken of without some contemptuous epithet. “Red shanks,” “Tar heels,” &c., are the names by which they are commonly known. The slaveholders look with infinite contempt upon these poor men—a feeling which they cherish for poor men every where.

But there is this mention of the name Pompey Tarheel in Philadelphia’s Neal’s Saturday Gazette and Lady’s Literary Museum of 22 January 1848:

Mrs. Farthingale was the other day overlooking a lazy son of Guinea in her employ, as he was sweeping down the sanded floor of the kitchen, and remarking the queer figures the dark one drew with his broom, observed:

"Well Caesar, you can draw, pretty well, can't you?"

"Yah, yes, gorramighty Missus, I can draw fust rate; last Saturday I took a policy for Pompey Tarheel, and I drawed fifty dollars."

Mrs. F. drew herself up into one of her highly dignified attitudes, and—left the kitchen.

Several scholars have taken the name Pompey Tarheel to be a reference to an enslaved person—naming enslaved Blacks after classical figures was common, as seen by the name Caesar here. But I think it may be the name of a racehorse, given the use of the word policy, which can refer to a promissory note made when making a wager. It's not uncommon for slang terms to make early appearances in print in the names of racehorses; edited publications might eschew slang terms in general, but they would print the names of horses in race results.

Then there is a use of Fred Douglass Tarheel in the Indiana Herald of 24 November 1852:

“Well, we are glad the election is over, if we did “come out a little horn.” Democrats will now discover that there are some decent people among the Whigs, and vice versa. A Whig lady can now lend her Democratic neighbor her coffee-mill, and in turn, borrow an egg to put in her pan-cakes. Andrew Jackson Croutcutter will now be allowed to play with Henry Clay Snakefeeder's pet hog; and Fred Douglass Tarheel will se-saw with John Quitman Screwdriver, and take the South side of the fence. All will go just as if one person were as good as another!

Again, the association here of tarheel with Douglass more likely arises out of his politics than because of his race. The proper names mentioned are fictional stand-ins for members of the two political parties, named after prominent members of them: Andrew Jackson and John Quitman were Democrats; Henry Clay and Frederick Douglass were Whigs. Of course, tarheel here could carry both a racial and a political connotation.

But the earliest use of tarheel to refer specifically to a North Carolinian is in reference to a Black man. It appears in California’s San Andreas Independent of 6 February 1858:

“Dont yah call dis er’n a Down-easter,” said Scip, “yah mis’ble dirt-eatin Norf C’lina tar-heel,” and with this he grew bellicose and pitched into Pomp, knocking his nose into something like a mashed potato putting Paddy’s seal on both his eyes, scattering half a pound of wool over the ground, and winding up an argument more creditable to the valor than the discretion of the chivalrous Pompey.

The question here, however, is to what degree was the epithet applied because of the man’s race as opposed to where he was from. So the association of tarheel with Blackness is a muddied one. The word could be applied to Blacks as well as whites, tar is often associated with Blackness, and the contexts that used tarheel to refer to a Black person were clearly racist. But it’s not clear that the term itself had a primary meaning of, or even a strong connotation of, race.

Tarheel becomes even more strongly, and even exclusively, associated with North Carolina during the Civil War, when soldiers in regiments from other Southern states used it to refer to North Carolina regiments. The North Carolinian soldiers took the epithet in stride and proudly claimed for their own. Thus the process of amelioration began, and today it is not only used proudly, but it lacks any racist association that it might have once had.

Sources:

I am indebted to Bonnie Taylor-Blake and Bruce Baker, who pioneered the scholarship of this term in recent years. Most of the citations in this entry were discovered by them.

Baker, Bruce E. “Why North Carolinians Are Tar Heels.” Southern Cultures, 21.4, Winter 2015, 81–94. DOI: 10.1353/scu.2015.0041. Project Muse. An open-access version without the source notes is available here.

Bayley, A. L. “To the Workingmen of Essex” (6 October 1846). Emancipator (Boston), 21 October 1846, 1/3. Gale Primary Sources: Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers.

“Carrying the War into Africa.” San Andreas Independent (California), 6 February 1858, 3/1. NewspaperArchive.com.

Dictionary of American Regional English Online, 2013, s.v. tarheel, n.

“Evening Lectures of Hetty Jones.” Fort Wayne Sentinal (Indiana), 16 September 1848, 1/5. NewspaperArchive.com.

Flint, Timothy. Recollections of the Last Ten Years. Boston: Cummings, Hilliard, 1826, 318–19. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

A Funny Man.” Indiana Herald (Huntington), 24 November 1852, 2/3. Newspapers.com.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, accessed 8 June 2025, s.v. tarheel, n., tarheel, adj., rosin heel, adj.

Letter (5 May 1826). Ariel (Natchez, Mississippi), 12 May 1826, 6/1. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. tarheel, n.

Taylor-Blake, Bonnie. “Tar heels [1846].” ADS-L, 11 April 2009.

———. “Unusual Use of ‘Tarheel’ (1848, 1852).” ADS-L, 21 September 2013.

———. “Who Put the ‘Tar’ in ‘Tar Heels’?: Antebellum Uses of the Epithet and Its Application to North Carolinians.” So They Say (blog), 29 April 2022.

“Whims and Oddities.” Neal’s Saturday Gazette and Lady’s Literary Museum (Philadelphia), 22 January 1848, 4/9. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Image Credit: W. P. Snyder, 1884. Harper’s Weekly, 17 May 1884, 312. HathiTrust Digital Archive. Public domain image.