suborn

Suborn is a verb that is usually heard in the context of lying under oath, and indeed roughly half of the instances of the verb in the Corpus of Contemporary American English are in the phrase suborn perjury. The verb clearly means to induce someone to commit a crime, but where does it come from?

Like many English legal terms, this one comes from French, a result of the Normans taking over the English legal system after 1066. In particular the English suborn comes from the Anglo-Norman suburner or subhorner, the meaning of which is remarkably consistent with the present-day English verb.

From a 1358 city of London statute:

Et plus curial chose serroit et accordaunt a ley et reson que homme se acquittat par son serment et siz bones gentz de jurer ovesqe lui ou par enquest de doze hommes qe par deux, issint subornés et faucement procures et enformés

(And because it would be more seemly and more according to law and reason that man should acquit himself his oath and that of six good people swearing with him, or by an inquest of twelve men, than by the witness of two thus suborned and tortiously procured and primed)

We see the English use of the word in the Parliamentary Rolls for 1430–31, in the case of Eleanor de Holland, wife of James Tuchet, 5th Baron Audley. She was trying to prove that her birth was legitimate and, therefore, that she was the heiress to her father, Edmund, Earl of Kent. A petition in the Rolls by Edmund’s sisters, who would otherwise inherit, alleges that she suborned false testimony:

Alianore, wyf to James, upon grete subtilite, ymagined processe, prive labour, and colored menes and weyes, to yentent yat she shuld be certified mulire be sum ordinarie, in case yat bastardie were alleged in her persone, hath broght in examination afore certein Jugges in Court Cristiene and Spirituell, nat enfourmed, nor havyng knawleche of ye saide subtilite, ymagined processe, prive labour, coloured menes and weyes, certeyns subornatz proves and persones of hir assent and covyne.

(Eleanor, wife to James, with great trickery, imagined process, secret labor, and deceitful means and ways, intending that she should be certified legitimate by some authority, in case that bastardy were alleged in her person, has brought in examination before certain judges in ecclesiastical court, not informed, nor having knowledge of the said trickery imagined process, secret labor, and deceitful means and ways, certain suborned proofs and persons with her assent and fraud.)

We don’t have a record of what the ecclesiastical court decided, but from the petition’s wording (the court being unaware of the alleged perjury) it appears that they decided in Eleanor’s favor. Regardless of the truth of the matter, Parliament granted the petition, and the sisters inherited.

Of course, with the word coming from French, we can trace suborn’s roots back to Latin, where the basic meaning of the verb subornare is to equip, to adorn, but where it was also used to refer to inducing or inciting a crime, especially perjury. For instance we have this from Cicero’s Pro Aulo Caecina 71, a speech he gave in 69 B.C.E.:

Itaque in ceteris controversiis atque iudiciis, quum quaeritur, aliquid factum necne sit, verum an falsum proferatur, et fictus testis subornari solet, et interponi falsae tabulae, nonnumquam honesto ac probabili nomine bono viro iudici error obiici, improbo facultas dari, ut, quum sciens perperam iudicarit, testem tamen aut tabulas secutus esse videatur.

(And so it often happens in the ordinary disputes that come before a court, when it is a question of whether something is or is not a fact or whether an allegation is true or false, that a false witness is suborned, forged documents are put in and sometimes, under the guise of fair and honest dealing, an honest juror is deceived or a dishonest juror afforded the chance of giving the impression that his wrong verdict, which was really intentional, was the result of his having been guided by the witness or the documents.)

The etymology of suborn is, therefore, quite ordinary and straightforward, but it is unusual in that the meaning and patterns of usage have been preserved pretty much unchanged for over two millennia.

Sources:

Anglo-Norman Dictionary, AND Phase 5 (R–S) 2018–21, suburné.

Bateson, Mary. Borough Customs, vol. 1 of 2. Seldon Society 18. London: Bernard Quaritch, 1904, 169–70. HathiTrust Digital Library.

Cicero. Pro lege Manila. Pro Caecina. Pro Cluentio. Pro Rabiro perduellionis reo. Jeffrey Henderson, ed. H. Grose Hodge, trans. Loeb Classical Library, Cicero 9, LCL 198. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1927, 166–69. Loeb Classical Library Online.

Middle English Dictionary, 4 March 2025, s.v. subornate, ppl.

Oxford English Dictionary Online, June 2012, s.v. suborn, v.

“Parliament. IX Hen. VI” (1430–31). Rotuli parliamentorum; ut et petiones, et placita in parliamento. Tempore Henrici R. V., vol. 4. London: 1767–77, 375b. Gale Primary Sources: Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

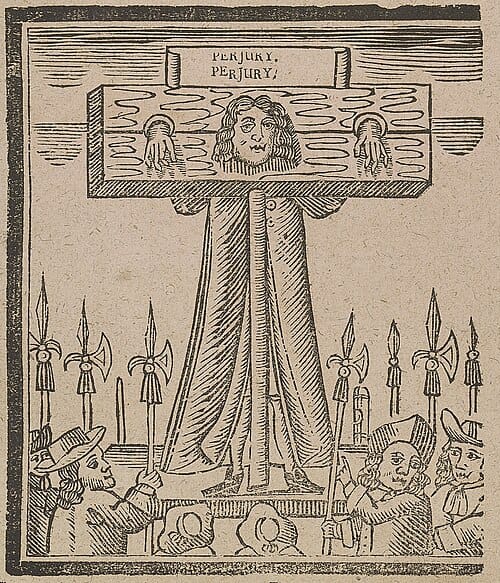

Image credit: unknown illustrator, c. 1686. Wikimedia Commons. English Broadside Ballad Archive. Public domain image.