robot / android

Robots are a staple of science fiction and increasingly an important part of life in our present-day world. The word comes from the Czech robota, a word literally meaning forced labor (the root rob means slave) but which is also used figuratively to mean drudgery, hard work. Robota has cognates in several Slavic languages, and the use of robot in English to refer to the system of serfdom in Eastern Europe dates to the early nineteenth century. Here is an example from John Paget’s 1839 Hungary and Transylvania that criticizes the system of robota, not because forced labor is inherently immoral, but because the system encourages sloth among the working class and doesn’t benefit the capitalists:

I believe that many of these laws have an injurious effect on the character of the peasantry. The system of rent by robot or forced labour,—that is, so many days ’ labour without any specification of the quantity of work to be performed,—is a direct premium on idleness.

The Austrian Empire abolished the system of robota following the 1848 revolutions that swept over Europe.

But the sense meaning an artificial being that can, in some fashion, take the place of a human is more recent. Czech writer Karel Čapek (1890–1938) created this new sense by modifying the word robota and coining robot in his 1920 play R. U. R. Rossum’s Universal Robots—the play was originally written and performed in Czech, but the name of the company was in English, which tells us something about the state of capitalism in Eastern Europe in the period. One of the play’s stage directions reads:

Ústřední kancelář továrny Rossum's Universal Robots. V pravo vchod. Okny v průčelní stěně pohled na nekonečné řady továrních budov. Vlevodalšířiditelské místnosti.

(The central office of Rossum's Universal Robots. On the right is the entrance. Windows in the front wall look out onto the endless rows of factory buildings. On the left are the other management offices.)

Čapek credited his brother Josef for helping him come up with the word.

The dystopian play, set in a robot factory, is about a world where humans rely on automated labor. The outline of the play’s plot, a robot rebellion against their human masters, is now a staple of science fiction (Terminator; Battlestar Galactica; I, Robot; 2001: A Space Odyssey; etc.), and this March 1922 summary of the play by Edward Moore has one of the first uses of this sense of robot in English:

Rossum’s Universal Robots (which one may translate as Knowall’s Universal Hands) is a firm for the production of mechanical men who have the advantage, from the commercial point of view, of working more efficiently than real men, and at a fraction of the cost. Being without desires, incapable of feeling pain or pleasure, or of laughing or crying, they are tremendously efficient, and after the lapse of ten years they not only do the world's work, but fight the nation's wars. At the same time, children cease to be born; nature, it appears, has no longer any need of man, and declines to give herself the trouble of producing him. The Robots, logical in everything, exterminate the human race until only one man is left, Alquist, an architect at the factory, who for his own salvation has always worked with his hands, and whom they spare on the equivocal ground that he is a Robot. The new masters of the world are left with the problem of reproducing themselves; a difficult question, for they do not know the trade secret and they are all due to die in twenty years, even the more recently-made among them who are superior in brain and in sensibility to the earlier Robots. Alquist is unable to do anything for them, but he happens to overhear two of them laughing together, and making love: and he realizes that life will go on again, and a new world will begin with a new Adam and Eve.

R. U. R. was a popular play and quickly translated into English, opening on Broadway in 1922. In a time where industrialization and factory labor was combining with rising totalitarianism (e.g., the 1917 Bolshevik revolution in Russia and the 1922 fascist rise to power in Italy), robot struck a chord that resonated with the times. The play was a hit on Broadway, and by December 1922 robot was being used in contexts divorced from Čapek’s play. Here is a syndicated film review that appeared in newspapers on 15 December 1922:

The only time acting was ever required of Edna Purviance, Chaplin’s leading woman, was in “The Kid.” She showed in that that she was wasting her talent by remaining in comics. Mildred Davis was an essential character in “Doctor Jack” and “Grandma’s Boy,” but in his other comedies Harold Lloyd could well have had a robot in her place.

A good sign that a word has entered the language to stay is when it is modified to form new words or used as a different part of speech, and indeed by 1924 the adverb robotically, meaning to act mechanically, without emotion, had been coined. In 1927 the adjective robotic was in use; Isaac Asimov was using robotics by 1941, and the combining form robo- was in place by 1945.

Čapek’s robots were human-like androids, but the word, especially in its actual application to real-world automatons, is often used for machines that do not resemble humans at all. This shift is not recent and goes back at least to 1927, almost as long as the word has been in use in English. In 1930, for example, automated traffic signals in London were dubbed robots. This particular use of the word has fallen out of use in British English, but survives in South Africa.

While Čapek coined this sense of robot, he did not invent the concept. The idea of human-like automatons, or androids, has been around for centuries. And the Czech origin of robot recalls the Jewish tradition of the golem, a robot-like servant made from mud. Golem is Hebrew for shapeless mass. And reinforcing the Czech origins of the concept of robots, the most famous tale of a golem takes place in sixteenth-century Prague, where rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel creates one to defend Prague’s Jewish ghetto from a pogram.

The English word android is borrowed from the French androïde, which is formed from andro- (Greek ἀνδρο-, man) + -oid (Greek -οειδής, form or likeness). Albertus Magnus (c. 1200–80) allegedly created a magical android, and accounts of this fictional accomplishment using the French word appear in English by 1657. From John Davies’s translation of Gabriel Naudé’s The History of Magick from that year:

And that is Original is true and well deduc’d, where is a manifest indicium, in that Henry d’Assia and Bartholomæus Siillus affirm, that the Androides of Albertus, and the Head made by Virgil, were compos’d of flesh and bone, yet not by Nature but by Art.

This definition of androides appears in Pantologia, an 1819 encyclopedia:

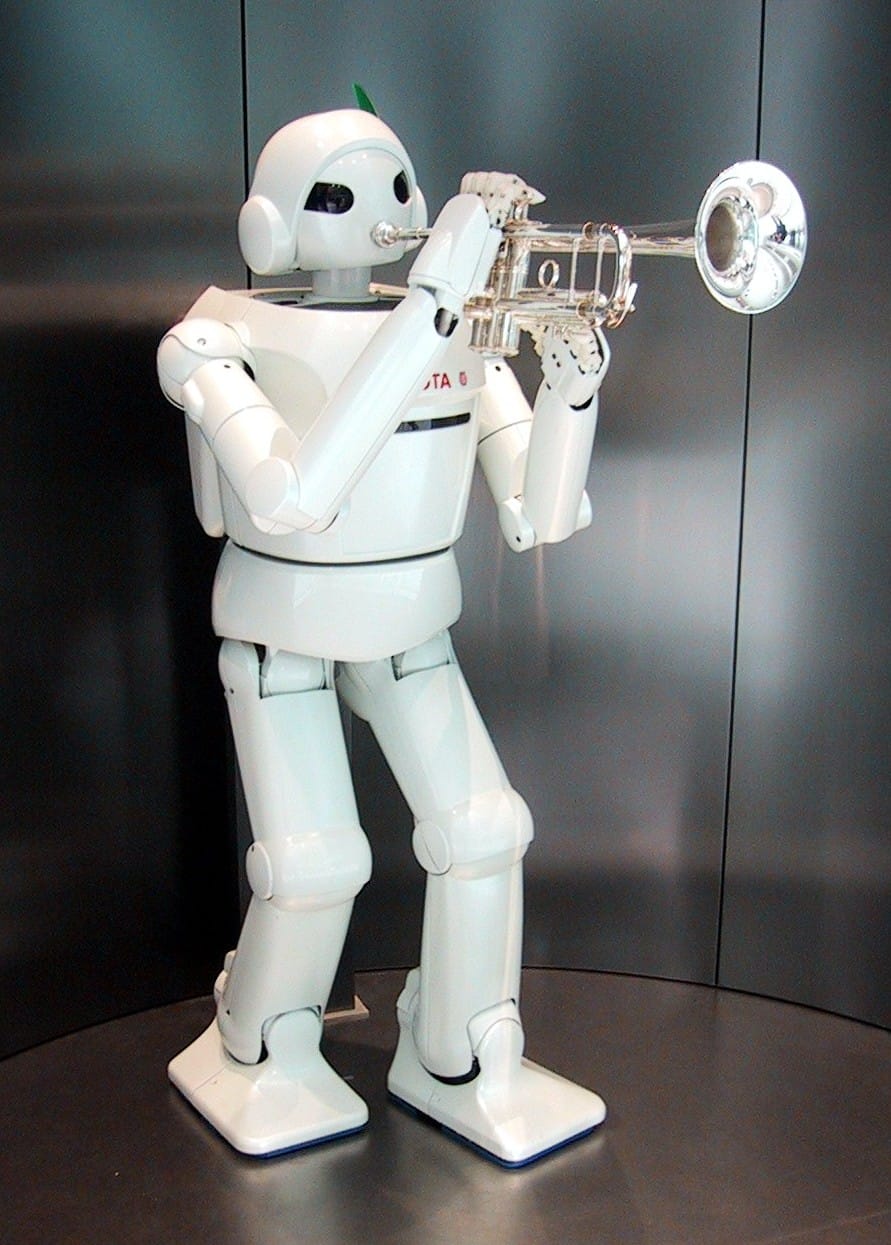

ANDROIDES. (ανηρ, ἀνδρο, man, and ειδος, form) A human figure, which, by certain springs or other movements, is capable of performing some of the natural motions of a living animal. The motions of the human body are more complicated, and consequently more difficult to be imitated, than those of any other creature; whence the construction of androides, in such a manner as to imitate any of these actions with tolerble exactness, is justly supposed to indicate greater skill in mechanics than any other piece of workmanship whatever.

This definition is followed by a description of a flute-playing android, on display in Paris in 1738.

But the use of android in science fiction postdates Čapek’s play. The following appears in Jack Williamson’s 1936 Cometeers:

“The illegal experiments of Eldo Arrynu,” Jay Kalam continued, still unhurried, “had been in the synthesis of life—repeated horrors long ago forced the council to outlaw such efforts.

“And upon the asteroid, he carried out his forbidden work to a triumphant completion. The traffic that brought him such enormous wealth was the production and sale of androids.”

For a moment the nearere shining thing seemed frozen. Red star and violet star ceased their regular beat. And the misty spindle between them was congealed into a pillar of green-white crystal. Then it broke into quivering motion, and a startled word cam out of it: “Androids!”

“Eldo Arrynu,” amplified Jay Kalam, “had come upon the secret of synthetic life. He generated artificial cells, and propagated them in nutrient media, controlling development by radiological and biochemical means.

He was an artist, as well as a scientist. The genius of creation was a supernal flame in him. He worked in living, synthetic flesh. He achieved miracles—diabolical miracles——"

The history of robots, both literary and industrial, reflects our ambivalence to the concept and the fear of humans assuming god-like powers of creation without god-like wisdom, whether it be fears of rebellion and genocide or simply those of unemployment.

Sources:

Čapek, Karel. R. U. R. Rossum’s Universal Robots. Prague: Aventinum, 1922, 7. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Dean, James. W. “Fraternity Foolishness is Basis for Very Funny Film.” Port Huron Times-Herald (Michigan), 15 December 1922, 8/3. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Good, John Mason, Olinthus Gregory, and Newton Bosworth. Pantologia, vol. 1 of 12. London: J. Walter, et al., 1819, s.v. androides. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction, s.v. robot, n. (18 March 2021); robotic, adj. (26 January 2025); robo-, prefix (18 March 2021); robotically, adv.1 (17 November 2024); robotically, adv.2 (20 December 2020); robotics, n. (16 December 2020); android, n. (5 December 2024).

Languagehat. “The Android of Albertus Magnus.” Languagehat.com (blog), 19 January 2013.

Moore, Edward. “Prague Letter” (March 1922). The Dial, April 1922, 407. ProQuest Magazine.

Naudé, Gabriel. The History of Magick. John Davies, trans. London: Joh Streater, 1657, 250. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2010, s.v. robot, n.2, robot, n.1, robotic, adj. & n.; September 2022, s.v. android, n. & adj.

Paget, John. Hungary and Transylvania, vol. 1 of 2. London: John Murray, 1839, 305–06. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Williamson, Jack. “The Cometeers” (conclusion). Astounding Stories, 17.6, August 1936, 121–52 at 146. Archive.org.

Photo credit: Chris 73, 2005. Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.