pork / pork barrel

It’s something of a cliché to say that English words for domesticated animals come from Old English while the words for various types of meat come from Norman French, as the English-speaking commoners cared for the animals and the French-speaking nobility ate the meat. It’s a gross simplification, with all the inaccuracies and exceptions that entails, but it's generally true. And our present-day word pork does indeed come from the Anglo-Norman porc. The Anglo-Norman (i.e., the dialect of French spoken in England following the Norman Conquest) comes from the Latin porcus, meaning pig.

The Anglo-Norman porc could refer to either the animal or its meat, and English use adopted this dual meaning, although use of the word to refer to the animal became increasingly rare after the Middle Ages.

English use of pork is recorded c. 1300 in a life of Mary Magdalene in the South English Legendary:

huy nomen with heom into heore schip : bred i-novȝ and wyn,

Venesun of heort and hynd : and of wilde swyn,

huy nomen with heom in heore schip : al þat hem was leof,

Gies and hennes, crannes and swannes : and porc, motoun and beof

(He took with him onto their ship enough bread and wine, venison of hart and hind, and of wild swine. He took with him on their ship all that he liked, geese and hens, cranes and swans, and pork, mutton, and beef.)

Note that venison originally referred to the flesh of any animal killed in the hunt, not just to deer meat. So the meat of wild boars was also venison.

Much more recently, pork and pork barrel have acquired a metaphorical meaning in American politics, that of government money doled out by legislators to local projects in their districts, with the implication of being unseemly if not downright corrupt. There are several popular misconceptions about how this sense came about, which I will address below, but it seems to have developed from a common expression, too much pork for a shilling, referring to anything that is excessive or over the top. And when applied to politics, early uses were just as likely to refer to politicians lining their own pockets rather than distributing goodies to constituents.

Too much pork for a shilling appears by 1834, and it was first used to describe purple prose or overly sentimental writing. We see it in a piece in the Nantucket Inquirer of 15 January 1834, and while the context is politics, the specific reference is to over-the-top oratory:

The New York Standard cruelly pokes fun at Mr. Polk’s polyacoustic hocupocus [sic], in the following strain of extravagant mockery:—“It is the most powerful and triumphant vindication that was ever delivered to a deliberative body in this or any other country. The declamations of Clay and M’Duffie are as fables to history when compared with the arguments of Col. Polk. He is one of the ablest men in the house or in the [c]ount[ry] &c.

M[r.] Hone! this is cutting a leetle too fat. Even Polk himself will say “there is too much pork for a shilling.”

And we get this from the Knickerbocker magazine of November 1841 from a letter to writer from his publisher:

Some folks like what’s pathetic—some do n’t; and I am one of them. Do n’t take it hard; but it’s high time you should know you are going too strong in that line. As for your heroine, she has done nothing but snivel and weep from first to last. We found her at it, and left her at it. It’s too much pork for a shilling. Now do give us something jolly—there’s a good fellow!

We see the phrase deployed to mean political favors in a statement by John W. Boyd, a newspaper editor who declined to run for mayor of Hagerstown, Maryland. The statement was printed many times over the decades as an example of political integrity, the earliest that I’ve found is in Philadelphia’s Sunday Dispatch of 14 May 1854:

But to put myself in a position in which every wretch entitled to a vote would feel himself privileged to hold me under special obligations, would be giving rather “too much pork for a shilling.” I, therefore, most emphatically decline the intended dishonor.

And two years later there is this from Lancaster, Pennsylvania’s Inland Weekly and Campaign Banner of 1 November 1856 using the term to refer to money wastefully donated to a political campaign:

In copying the foregoing, the N. Y. Times adds the following:

“This explains the recent quasi Democratic success in Pennsylvania. We have it from good authority that not less than $150,000 was sent into the State by the slaveholding States,—in addition to the $50,000 contributed by the Rothschilds, through Mr. Belmont and the $100,000 raised from the bankers and brokers of Wall street. It is probable that very nearly $500,000 was expended by the Democratic party in carrying out the late State election. How much of it went into the pockets of the wire-pullers of the Fillmore party, probably those whom they deluded into aiding the triumph would be gald [sic] to know.”

We imagine they have by this time concluded that they gave “too much pork for a shilling.” They have elected their Canal Commissioner by less than 3,000: one branch of the Legislature is hopelessly against them—and on the Congressional vote their majority is whittled down to almost nothing. They will have to draw their draft for another half a million.

But ten years later the phrase is being used to denote political favors bestowed by officeholders. This is from Camden, New Jersey’s West Jersey Press of 29 August 1866. James Scovel was a state legislator from Camden and a rare example of a New Jersey politician who was not corrupt, or who at least wasn’t cheap (I’m New Jersey born and bred, so I can get away with snide criticism of the state, but outsiders dare not try):

The best reason Scovel has yet given for going back on the copperheads he gave to a Democratic friend last week. He said they wanted “too much pork for a shilling.” Satisfactory very.

(During the US Civil War, the copperheads were northern Democrats who sympathized with the Confederacy and advocated an immediate end to the war.)

We finally see a political use of pork and pork barrel, divorced from the phrase too much pork for a shilling, by 1873, but this piece links those terms to an old joke about a Jew (sometimes it’s a Muslim) eating pork. And again, this use of pork and pork barrel is in the context of congressional salaries, not disbursement of funds. From the Springfield Daily Republican of 14 July 1873:

Once upon a time, as tradition reports, there lived a worthy Israelite who was tormented by a hankering after the forbidden food. At last, his curiosity and appetite got the better of his religious principles; he ordered a pork-chop for dinner. Absorbed in the sinful, delightful repast, he did not notice the approach of a thunderstorm. Suddenly a loud clap set the windows rattling. Dropping his knife and fork in panic—“Holy Abraham,” he exclaimed, “what a fuss about a little piece of pork!”

A good many honorable senators and representatives regard the storm of popular indignation now blowing with very much the same feeling. They are scared, but they are also aggrieved. They find it quite uncalled for and out of proportion to the exciting cause. Recollecting their many previous visits to the public pork-barrel, the much bigger loads lugged away on those occasions, the utter indifference displayed by the people, this hue-and-cry over the salary grab, actually seeming to grow louder from month to month, puzzles quite as much as it alarms them. They had not counted on it all, and they find it very unreasonable and absurd. “What a fuss about a little piece of pork!” says Gen Butler in his famous postage-stamp letter. “What a fuss about a little piece of pork!” echoes Senator Carpenter in his Janesville speech. In all the published apologies and defenses, we detect this sense of injury, this accent of complaint and remonstrance.

We see the phrase congressional pork barrel in Boston’s Sunday Herald of 31 May 1896, but this is a brief snippet, a line included to fill out a column, so exactly what is meant by it is unclear:

The congressional pork barrel seems quite likely to be re-coopered.

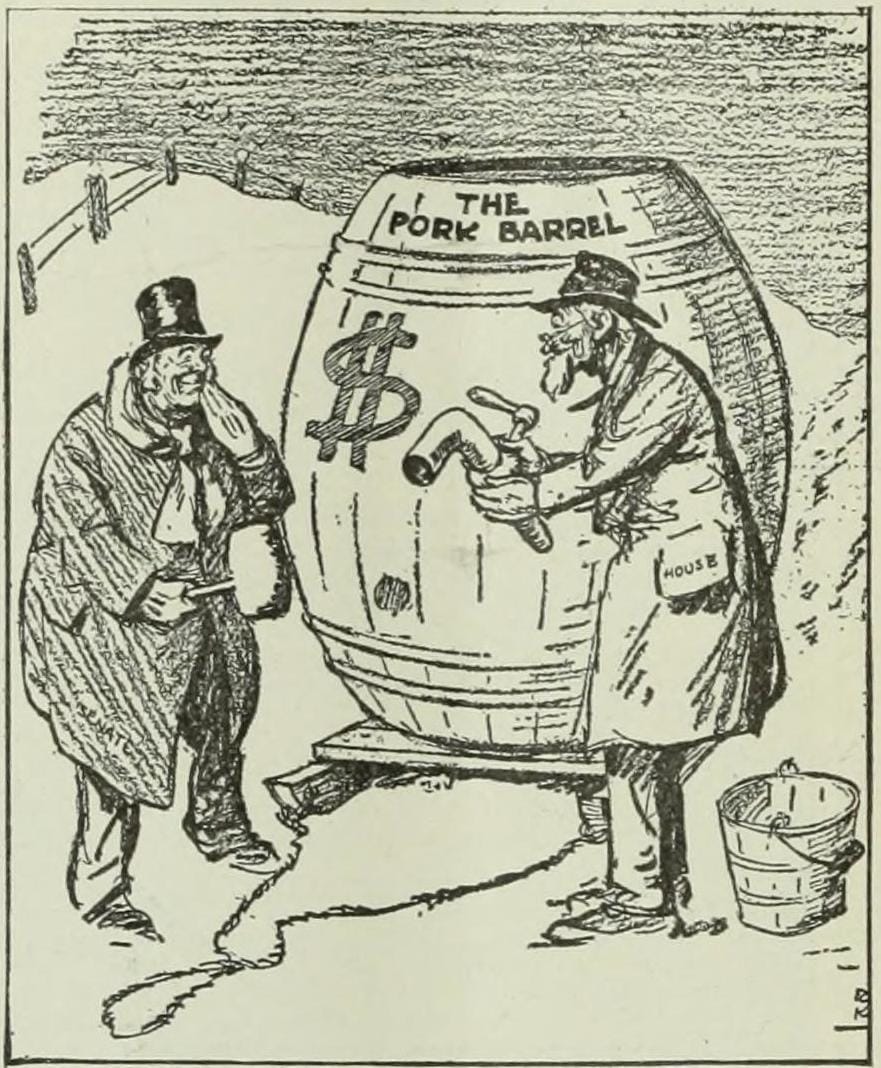

We see both pork and pork barrel used in the sense we’re familiar with today in Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine of September 1896:

Another illustration represents Mr. Ford in the act of hooking out a chunk of River and Harbor Pork out of a Congressional Pork Barrel valued at two hundred and fifty thousand dollars, “which,” to quote the author, “the Miner’s Association of California wanted, but which really belonged to Boston."

And finally, there is this from Trenton Sunday Advertiser of 11 December 1904:

Speaker Cannon is evidently girding up his loins to put up a fight against the treasury raiders at this session. The widening gap between the revenues and expenditures of the government is giving the administration grave concern. As “Uncle Joe” states the proposition in his blunt and breezy manner of speech, “there’s a gap of about $30,000,000 between the vest and the pants.” Under such circumstances the congressional “pork barrel” is likely to be of smaller dimensions than usual this time; but it is sincerely hoped that the appropriation desired for the enlargement of the Trenton Post Office will be granted. The necessity for the improvement exists, and is urgent, and neither “graft” nor “pork” is involved in the application for the needed money.

It is commonly claimed that the political sense of pork and pork barrel comes out of chattel slavery in the American antebellum South, where enslavers would distribute barrels of pork to feed their enslaved workers. But there is no evidence linking the terms to slavery. Instead we see a gradual development starting with the catchphrase too much pork for a shilling being used in a variety of contexts, including politics, and it is not until well after the Civil War and the end of chattel slavery that either pork or pork barrel are used in the political sense. And the present-day sense of political favors dispensed to constituents is not cemented until the turn of the twentieth century.

Sources:

Anglo-Norman Dictionary, 2013–17, porc, n.

“Ford’s Life in Washington.” Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine, September 1896, 370. ProQuest Magazines.

“Freemen of Pennsylvania, Read the Following and Learn.” Inland Weekly and Campaign Banner (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), 1 November 1856, 8/1. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, n.d., s.v. pork, n.

“Magdelena.” The Early South-English Legendary. Carl Horstmann, ed. Early English Text Society. London: N. Trübner, 1887, lines 341–44, 472. Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Laud 108, fol. 193v–194r. Middle English Compendium.

Middle English Dictionary, 2025, s.v. pork(e, n.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, December 2006, s.v. pork, n.1, pork barrel, n.2.

“The Quod Correspondence, Number Six.” The Knickerbocker, 18.5, November 1841, 420. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

“The Real Significance of It.” Springfield Daily Republican (Massachusetts), 14 July 1873, 4/3. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Shearings and Clippings.” Sunday Dispatch (Philadelphia), 14 May 1854, 4/6. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Sunday Herald (Boston, Massachusetts), 31 May 1896, 12/8. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Too Much Pork for a Shilling.” West Jersey Press (Camden, New Jersey), 29 August 1866, 2/3. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Trenton Sunday Advertiser (New Jersey), 11 December 1904, 4/1. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Una voce Poco fa.” Nantucket Inquirer (Massachusetts), 15 January 1834, 3/1. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Image credit: Unknown artist, New York World, 1917. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.