patient zero

The term patient zero is an epidemiological term for the person who transmits an infection into a population that had been free of it. The term arose during the initial stages of the AIDS pandemic as a misinterpretation of the label Patient O—a capital letter O, not a zero—in data collected by the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC). The letter O stood for “outside of California,” since the study initially focused on patients in Los Angeles.

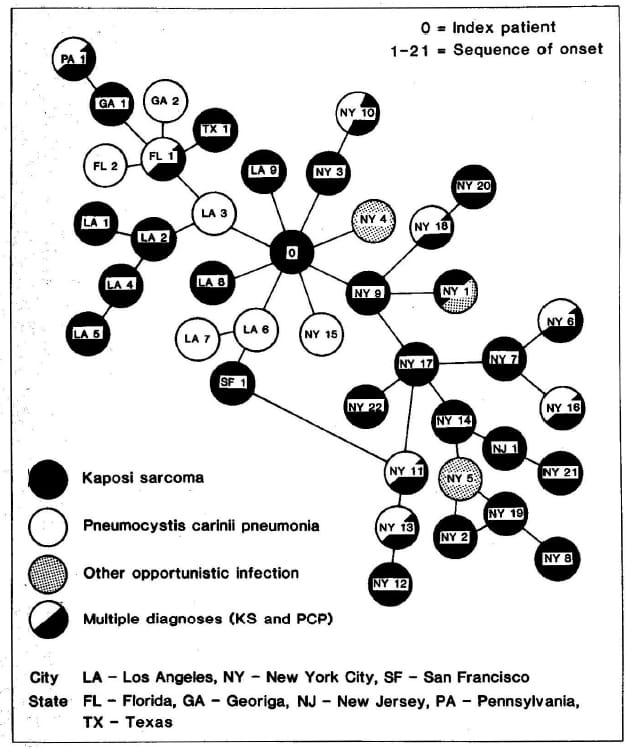

In the CDC’s March 1984 published study, the O was converted to a 0 (zero), and the other patients were labeled by letters and a number indicated their place of residence and sequence of diagnosis (e.g., Patient LA 9 was ninth person in the cluster from Los Angeles to be diagnosed; NY 9 was the ninth from New York to be diagnosed):

AIDS developed in four men in southern California after they had sexual contact with a non-Californian, Patient 0. […] Because Patient 0 appeared to link AIDS patients from southern California and New York City, we extended our investigation beyond the Los Angeles-Orange County metropolitan area.

This shift had the unfortunate result of making it seem as if Patient 0 was the source of the disease in this cluster, because zero precedes one and because of an association with the nuclear targeting term ground zero. But Patient 0 was not the first person in North America to contract the disease, and in fact he was probably not even the first in that cluster to contract the disease—in fact, he himself may have contracted the disease from one of the eight men in the cluster with whom he had had sex. He was simply the person through whom all forty men in the cluster were linked, although he had had sexual contact with only eight of them.

The earliest use of patient zero (spelled out) that I have been able to find is in the 1 May 1984 issue of The Advocate:

NOTES ABOUT PATIENT ZERO

The headlines ran something like “40 AIDS Cases Linked to 1 Carrier” (USA Today) on March 27, when word of a CDC team’s paper about a cluster of cases got out. The CDC paper in the March issue of the American Journal of Medicine, describes sexual contacts that had been investigated among 40 gay men, tracing all to contact they had at some point with a man identified as “Patient 0,” who had, allegedly, infected his partners in Los Angeles, New York City, San Francisco, Florida, Georgia, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Texas.

The Advocate’s article errs in describing the geographical range of Patient 0’s sexual contacts. He had had sex with only eight men in the study, four from New York City and four from Los Angeles. The others in the study had sexual contact with either those eight or others in the study.

But the widespread use of patient zero came about following the publication of Randy Shilts’s 1987 And the Band Played On, a book about the early years of the AIDS pandemic. Shilts identified a French-Canadian flight attendant by the name of Gaëtan Dugas as patient zero:

By the time Bill Darrow’s research was done, he had established sexual links between 40 patients in ten cities. At the center of the cluster diagram was Gaetan Dugas, marked on the chart as Patient Zero of the GRID epidemic. His role was truly remarkable. At least 40 of the first 248 gay men diagnosed with GRID in the United States, as of April 12, 1982, either had sex with Gaetan Dugas or had had sex with someone who had.

In addition to continuing the misidentification of the letter O with the number 0, Shilts unfairly smeared Dugas with the inference that he was the vector for the disease's entry into and spread in North America, something of a 1980s version of Typhoid Mary. And from Shilts’s description of Dugas, readers came away with the impression that he was something of a monster. According to this image, not only was he extraordinarily promiscuous, but he also carelessly, or even deliberately, infected others after he knew he had the disease. There is no evidence to support either of these ideas. The number of Dugas’s sexual partners was similar to that of others in the cluster, and he was quite cooperative with the CDC investigators, even flying to Atlanta to assist in the epidemiological study. And since at the time no one knew that the disease that would become known as AIDS was sexually transmitted, one can hardly blame Dugas for infecting others. Ironically, it was Dugas’s cooperative attitude and ability to recall the names of his many sexual partners that both made him especially valuable to the investigators and led to the impression that he was a particularly effective vector of the disease. Dugas died of AIDS in March 1984, shortly after the CDC study was published.

So if Dugas was not the source of the disease, where did it come from? A study published in Nature in November 2016 of genetic evidence of HIV strains shows that the disease migrated from Africa to Haiti in the 1960s, and from Haiti to New York City by the early 1970s. Trying to pinpoint the exact source of the disease is valuable from an epidemiological standpoint, but dwelling on it in the press and identifying the individual is ethically questionable, running the risk of placing the blame on a person rather than the virus, as was done with Dugas.

By 1990, the term patient zero was being applied outside the context of AIDS. An 8 January 1990 article in the Arizona Republic made jocular use of the term in the context of a computer virus:

“I feel like I’ve got VD,” he said of his VDT [i.e., video display terminal] disease. “Today, I’ve been on the phone calling all my contacts.”

I started to feel sorry for the guy. He should have used protection—they have programs for that.

He had been the innocent victim of a malicious person who deliberately infected his system. Somewhere, some demented nerd was Patient Zero in this rapidly spreading epidemic.

Note this particular use alludes to the myth of Dugas deliberately spreading AIDS.

A few months later, on 18 March 1990, Florida’s Palm Beach Post used patient zero in the context of a local measles outbreak:

Health officials backtracked from a group of six victims at Lake Worth Christian School to establish that the girl who traveled to West Virginia was the “patient zero” of this year’s measles outbreak.

That’s how relabeling of the letter O as a zero and a misunderstanding of exactly what an epidemiological cluster study is led to the coining of patient zero.

Sources:

Auerbach, David M., William W. Darrow, Harold W. Jaffe, and James W. Curran. “Cluster of Cases of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome: Patients Linked by Sexual Contact.” American Journal of Medicine, 76.3, March 1984, 487–92 at 489.

Ellicott, Val. “County Health Officials Track Elusive Trail of Measles Cases.” Palm Beach Post (Florida), 18 March 1990, B1/4. ProQuest Newspapers.

Fain, Nathan. “Health: Aftershocks from the Bay Area.” Advocate, 393, 1 May 1984, 14–15 at 15. ProQuest Magazine.

Kahn, Alice. “Sorrowful Tale of a Good Disk that Slipped.” Arizona Republic (Phoenix), 8 January 1990, B4/1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2005, s.v. patient zero, n.

Shilts, Randy. And the Band Played On: Politics People and the AIDS Epidemic. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987, 147. Archive.org.

Worobey, Michael, et al. “1970s and ‘Patient 0’ HIV-1 Genomes Illuminate Early HIV/AIDS History in North America.” Nature, 539, 3 November 2016, 98–105 at 99–100.

Image credits:

Typhoid Mary: unknown photographer, 1907. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain photo.

CDC cluster: David Auerbach, et al., American Journal of Medicine, 76.3, March 1984, 487–92 at 489. Fair use of a single, low-resolution diagram from a published study to illustrate the topic under discussion.