palladium

Palladium is actually two words, with distinct, albeit related, etymological paths and meanings. The older use of the word comes from Greek myth, the newer one is the name of element 46.

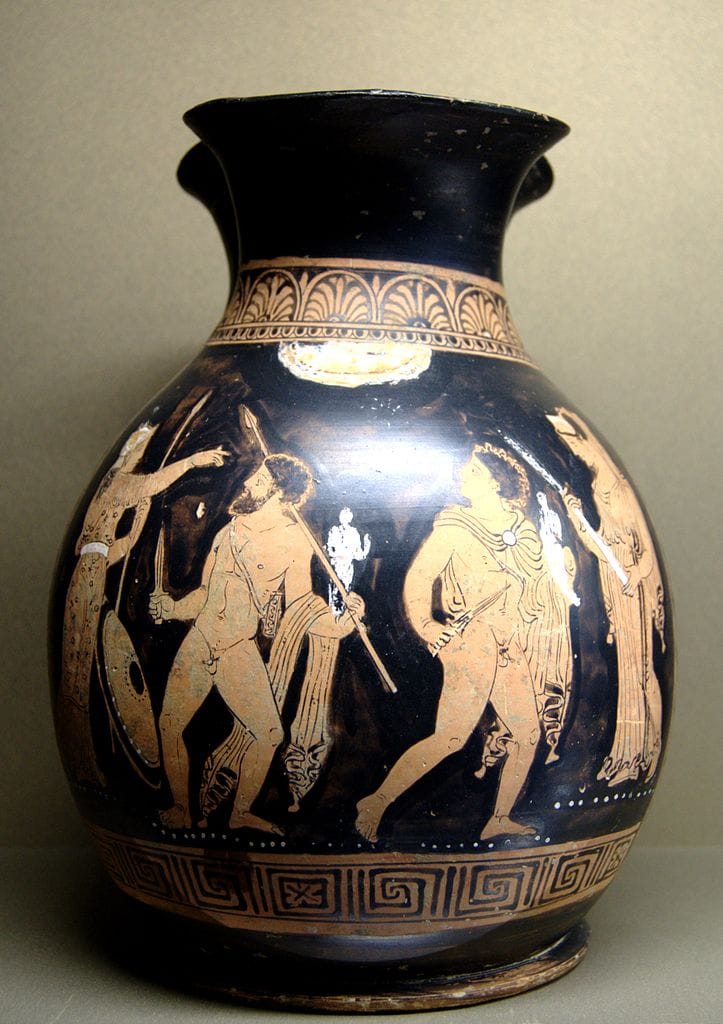

The original sense of palladium (often capitalized) was the name of a statue of the goddess Athena in the city of Troy. Supposedly, as long as the statue was within its walls, the city could never by conquered. But the Greek warriors Odysseus and Diomedes slipped into the city during the siege and stole the statue. Use of the name in English appears by the late fourteenth century, borrowed from the French and Latin palladium. The Latin comes from the Greek Παλλάδιον (Palladion), formed from Παλλαδ- (Pallad- from the epithet Παλλάς (Pallas) of the goddess Athena) + ‑ιον (-ion, diminutive suffix).

Geoffrey Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde (c.1385) has this:

But though the Grekes hem of Troie suetten,

And hir cite biseged al aboute,

Hire olde usage nolde they nat letten,

As for to honoure hir goddes ful devoute;

But aldirmost in honour, out of doubte,

They hadde a relik, heet Palladion,

That was hire trist aboven everichon.

(But though the Greeks shut in those of Troy,

And besieged their city all about,

They did not wish to leave off their old customs

As to very devoutly honoring their gods;

But in utmost honor, out of reverence,

They had a relic, called Palladium,

That was their trusted object above everything.)

By the beginning of the seventeenth century, palladium had been generalized to refer to some venerated object that served as a safeguard or protector. We see this general sense in Philemon Holland’s introduction to his 1600 translation of Livy’s history:

Now in these 35 bookes, so few as they be, preserved as another Palladium out of a generall skarefire, we may conceive the rare and wonderfull eloquence of our writer in the whole.

The name of the element is much more recent, dating to 1803. Palladium is a silvery metal with atomic number 46 and the symbol Pd. The metal has many uses, with over half the world’s supply used in automobile catalytic converters. But it is also used in electronics, medicine and dentistry, hydrogen fuel cells, and in jewelry.

The element’s name was formed in English from Pallad- (Παλλαδ-) + -ium. But in this case the name is not taken directly from the epithet for Athena, but rather from the newly discovered asteroid Pallas, which in turn is named for the goddess (cf. cerium and asteroid / Ceres / Pallas / Juno / Vesta).

The metal was discovered and named by William Hyde Wollaston in 1802, but the chemist, wishing to make a profit from his discovery and to keep the process for refining it secret, did not publish in the usual journals. Instead he anonymously offered samples of the metal for sale. The name palladium first appears in a leaflet advertising the sale. The text of the leaflet is reproduced in a paper on the metal by Richard Chenevix appearing in the 1803 volume of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London:

Palladium, or new silver, has those properties amongst others that shew it to be a new noble metal.

1. It dissolves in pure spirit of nitre, and makes a dark-red solution. 2. Green vitriol throws it down in the state of a regulus from this solution, as it always does gold from aqua regia. […] 8. But, if you touch it, while hot, with a small bit of sulphur, it runs as easily as zinc.

It is sold only by MR. FORSTER, at No. 26, Gerrard-street, Soho, London; in samples of five shillings, half a guinea, and one guinea each.

In 1805, Wollaston finally wrote about his discovery in Philosophical Transactions, revealing himself as the discoverer and the reason for the name:

I shall on the present occasion confine myself principally to those processes by which I originally detected, and subsequently obtained another metal, to which I gave the name of Palladium, from the planet that had been discovered nearly at the same time by Dr. Olbers.

Sources:

Chaucer, Geoffrey. Troilus and Criseyde. Stephen A. Barney, ed. New York: W. W. Norton, 2006, lines 1.148–54, 17.

Chenevix, Richard. “Enquiries Concerning the Nature of a Metallic Substance Lately Sold in London, as a New Metal, Under the Title of Palladium” (12 May 1803). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 93 (1803), 290–320 at 290. DOI: 10.1098/rstl.1803.0012.

Holland, Philemon. “To the Reader.” In Livy. The Romane Historie. Philemon Holland, trans. London: Adam Islip, 1600, n. p. Early English Books Online.

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. Palladioun, n.

Miśkowiec, Pawel. “Name Game: The Naming History of the Chemical Elements: Part 2—Turbulent Nineteenth Century.” Foundations of Chemistry, 8 December 2022. DOI: 10.1007/s10698-022-09451-w.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, March 2005, s.v. palladium, n.1, palladium, n.2.

Wollaston, William Hyde. “On the Discovery of Palladium; with Observations on Other Substances Found with Plantina,” (4 July 1805). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 95 (1805), 316–330 at 316. DOI: 10.1098/rstl.1805.0024.

Photo credit: Bibi Saint-Pol, 2007. Louvre Museum, Paris. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.