nobelium

In theory, the naming of new chemical elements should be rather straightforward: the scientists who first discover/synthesize the element suggest a name, which is officially approved by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). But the naming of element 102, nobelium, is twisted and fraught with controversy as three different research groups battled for decades over the right to name the element.

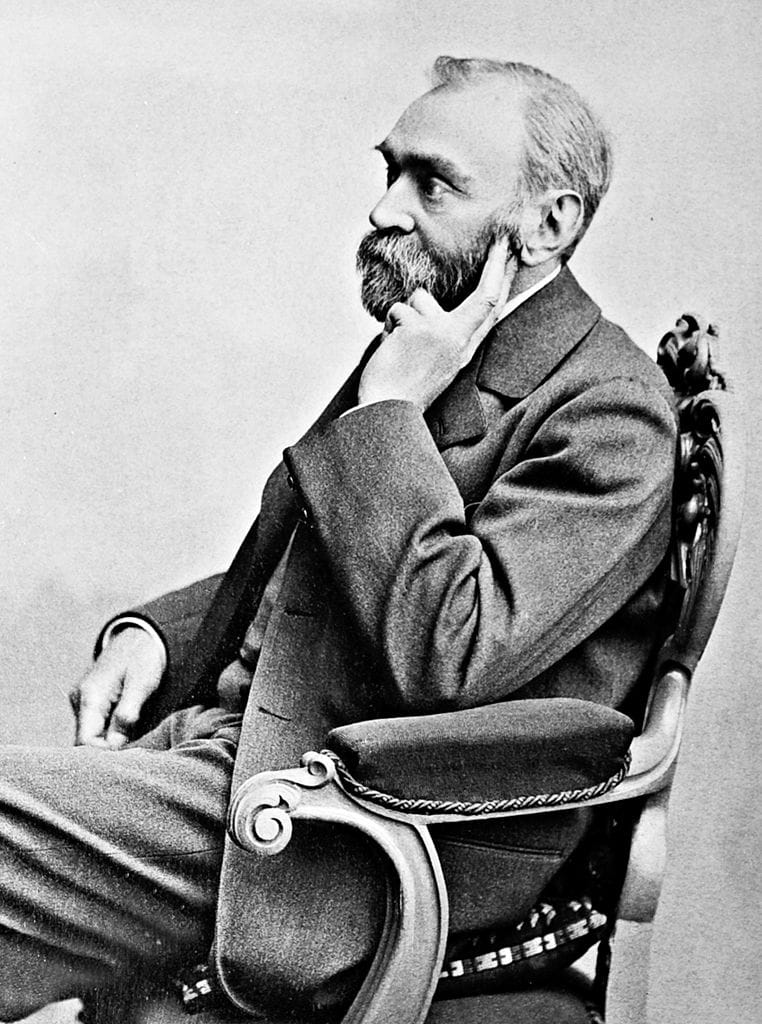

Nobelium is a synthetic chemical element with atomic number 102 and symbol No. It is, of course, named after Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, gelignite, and ballistite and endower of the research prizes that bear his name. Nobelium has no uses beyond pure research since its most stable isotope has a half-life of less than an hour.

Three different research teams claimed to have been the first to synthesize the element: 1) a team comprising scientists from the Nobel Institute for Physics (Stockholm, Sweden), Argonne National Laboratory (Lemont, Illinois), and the British Atomic Energy Research Establishment, (Harwell, UK); 2) a team from the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory (Berkeley, California); and 3) a team from the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (Dubna, Russia).

The Swedish/Argonne/British team was the first to make a claim of synthesizing the element, suggesting the name nobelium, and the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) quickly recognized the discovery and the name. The first mention of the synthesis and the name is in the 20 July 1957 issue of Science News Letter:

The U.S. and British scientists suggest the name, nobelium, for the heaviest element. The Institute where the work was performed is named in honor of the Swedish chemist, the late Alfred Nobel, who established the Nobel Prizes awarded annually for outstanding contributions in the arts and sciences.

The group officially published their results in a letter in the September 1957 issue of Physical Review:

We suggest the name nobelium, symbol No, for the new element in recognition of Alfred Nobel's support of scientific research and after the institute where the work was done.

The results, however, were not without controversy. The other two groups could not repeat the experiment, and it was subsequently shown the Swedish-led team did not, in fact, synthesize the element. The Berkeley team claimed to have possibly synthesized the element in 1959 and suggested keeping the name nobelium. But again the results of the experiment were uncertain. The Soviet team claimed to have synthesized the element in 1966 and suggested the name joliotum with the symbol Jo, after chemist and physicist Irène Joliot-Curie, the daughter of Pierre and Marie Curie.

In 1994, IUPAC revisited the claims and verified the Dubna team was the first to undisputedly synthesize the element, although it also found that the Berkeley team may have done so earlier. IUPAC kept the name nobelium, however, because the name had been in wide use for decades. This decision drew further protest from the Dubna laboratory, and in 1995 IUPAC changed the official name to flerovium. This sparked even further protests from the Swedes, Americans, and British, and in 1997 IUPAC took the unprecedented step of rescinding its rescinding of the name, restoring the name nobelium to element 102. The name flerovium would eventually be assigned to element 114.

So once again, the name of Alfred Nobel, the arms manufacturer turned benefactor to science, the arts, and peace, was mired in controversy.

Sources:

Fields, P. R., et al. “Production of the New Element 102” (19 July 1957). Physical Review, 107, 1 September 1957, 1460–62 at 1461. American Physical Society: Physical Review Journals Archive.

Hoffman, Darleane C., Diana M. Lee, and Valeria Pershina. “Transactinide Elements and Future Elements” in The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements, fourth edition, vols. 1–6, Lester R. Morss, Norman M. Edelstein, and Jean Fuger, eds. Dordrecht: Springer, 2011, 1652–1752 at 1660–61. SpringerLink.

“Make New Element 102.” Science News Letter, 72.3, 20 July 1957, 35. JSTOR.

Miśkowiec, Pawel. “Name Game: The Naming History of the Chemical Elements—Part 3—Rivalry of Scientists in the Twentieth Century.” Foundations of Chemistry, 12 November 2022. DOI: 10.1007/s10698-022-09452-9.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, December 2003, s.v. nobelium, n.

Photo credit: Gösta Florman, late nineteenth century. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.