moonstruck

We all know that people in love sometimes act insane, and that is the concept behind the modern use of the word moonstruck. Someone who is moonstruck is out of their mind with love. But this was not always the case; the word originally simply referred to insanity. The idea that the phases of the moon could trigger mental illness is an old one—English use of the word lunatic dates to the late thirteenth century—and that’s where the concept of being moonstruck comes from.

Moonstruck is recorded as early as 1647 in a sermon by John Arrowsmith, in which he expounds on the metaphor of the moon as a symbol of the decadent world—full of spots, representing sin; subject to change; and:

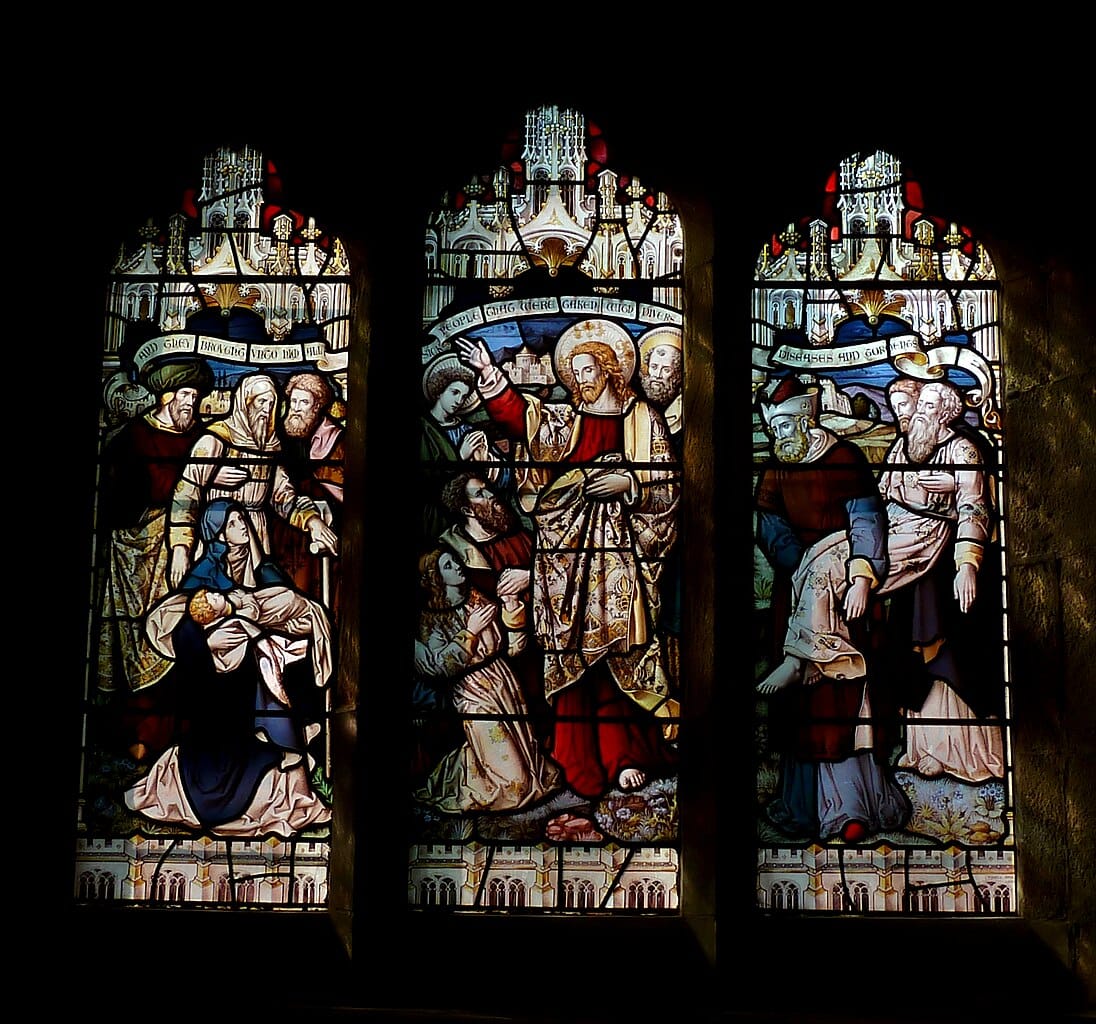

The cause of many diseases, especially of the falling-sicknesse. Scripture speaking of such as were troubled therewith, calls them σεληνιαζομένους Lunaticks or moon-struck, Mat.4.24.

Σεληνιαζομένους (seliniazoménous), found in the original Greek of the gospel, literally means moonlit. The full text of Matthew 4:24, in the 1611 Authorized (King James) Version reads:

And [Jesus’s] fame went throughout all Syria: and they brought unto him all sick people that were taken with divers diseases and torments, and those which were possessed with devils, and those which were lunatick, and those that had the palsy; and he healed them.

The New Revised Standard Version translates the Greek word as “epileptics.”

Moonstruck also appears in John Milton’s 1674 version of Paradise Lost, Book 11, in a vision shown by Michael to Adam of the consequences of his and Eve’s indiscretion with the forbidden fruit:

Immediately a place

Before his eyes appeared, sad, noysom, dark,

A Lazar-house it seemd, wherein were laid

Numbers of all diseas’d, all maladies

Of gastly Spasm, or racking torture, qualmes

Of heart-sick Agonic, all feavorous kinds,

Convulsions, Epilepsies, fierce Catarrhs,

Intestin Stone and Ulcer, Colic pangs,

Daemoniac Phrenzie, moaping Melancholie,

And Moon-struck madness, pining Atrophie,

Marasmus, and wide-wasting Pestilence,

Dropsies, and Asthma’s, and Joint-racking Rheums.

But in the mid-nineteenth century the meaning of moonstruck shifted and acquired an association with love and romance. To the Victorians, to be moonstruck was to be madly in love, combining the idea of madness with a moonlit lovers’ tryst. Charles Dickens used the word in association with love when he describes the title character of his 1850 novel David Copperfield:

The first thing I did, on my own account, when I came back, was to take a night-walk to Norwood, and, like the subject of a venerable riddle of my childhood, to go “round and round the house, without ever touching the house,” thinking about Dora. I believe the theme of this incomprehensible conundrum was the moon. No matter what it was, I, the moon-struck slave of Dora, perambulated round and round the house and garden for two hours, looking through crevices in the palings, getting my chin by dint of violent exertion above the rusty nails on the top, blowing kisses at the lights in the windows, and romantically calling on the night, at intervals, to shield my Dora—I don't exactly know what from, I suppose from fire. Perhaps from mice, to which she had a great objection.

Shortly afterwards, Matthew Arnold, in his 1852 Tristram and Isuelt, uses the word in the same sense:

All red with blood the whirling river flows,

The wide plain rings, the daz’d air throbs with blows.

Upon us are the chivalry of Rome—

Their spears are down, their steeds are bath’d in foam.

“Up, Tristram, up,” men cry, “thou moonstruck knight!

What foul fiend rides thee? On into the fight!”

—Above the din her voice is in my ears—

I see her form glide through the crossing spears.—

Iseult! . . . .

The older sense of plain madness and lunacy quickly dropped away and moonstruck came to mean dazed by love.

There are some other senses of moonstruck based on various superstitions about the effects of moonlight. Some believed that sleeping in moonlight could cause blindness, and those afflicted with this supposed moon-blindness were sometimes called moonstruck. Nineteenth-century sailors believed that the tropical moon would spoil fish, and said fish were said to be moonstruck. Of course, it was the tropical heat, and not the moonlight, that caused the fish to spoil, but superstition seldom has any truck with common sense. And various and sundry other afflictions were attributed to being struck by moonlight. Most of these are seldom found today, but you may run across them if you read enough nineteenth century literature.

Sources:

Arnold, Matthew. “Tristram and Iseult.” In Empedocles on Etna and Other Poems. London: B. Fellowes, 1852, 120–21. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Arrowsmith, John. A Great Wonder in Heaven. London: R. L. for Samuel Man, 1647, 19. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

The Bible, Authorized King James Version. Oxford World Classics. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1997, Matthew 4:24.

Dickens, Charles. David Copperfield, London: Chapman & Hall, 1850, chapter 33, 374–75. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Milton, John. Paradise Lost. London: S. Simmons, 1974, Book 11, lines 477–88, 299–300. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, December 2002, s.v. moonstruck, adj.

The New Oxford Annotated Bible, augmented third edition (NRSV). Oxford: Oxford UP: 2007, Matthew 4:24.

Photo credit: Storye book, 2016. Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.