misdemeanor / high misdemeanor

15 December 2025

As even non-lawyers know, in current U.S. legal parlance a misdemeanor is a less serious crime, whereas more serious crimes are classified as felonies. But what is the origin of the term? And how did it come to be used in the context of presidential impeachments in the phrase high crimes and misdemeanors?

Demeanor means conduct, so a misdemeanor is literally bad conduct. It comes from the verb to demean, meaning to conduct, to transact business and to behave oneself. Both senses of demean date to the 14th century. In Old French, the verb dates to the eleventh century, where it appears in La Chanson de Roland.

The original sense of misdemeanor is an offense that is punishable by forfeiture of property rather than imprisonment. The word dates to 1487 in the gerundial form misdemeaning, when Henry VII directed that an annuity that had been granted to one John Morris be given to someone else because Morris had supported Henry’s Yorkist enemies:

It pleased your Highnesse to directe your L[ord]res Missyve unto your said Oratours, the Abbott and Covent, to graunte the said Corrodie to oon John Wilkynson; bi force of whiche, your seid Oratours made their Graunte under their Covent Seale unto the seid John Wilkynson, hoping and trustyng, that they shuld have be discharged of the said Corrodye, rather made and graunted to the said John Morys, remembring and considering, that he had it, was by the nomination and desire of your said grete enemy’ and also for othre misdemenyng of the said John Morys ayenst your Highnesse, at the tyme of your said moost gracious aryvall and comyng into your said Realme.

The form misdemeanor appears in a 1503–04 law code, Act 19 Hen. VII, c. 12:

And that the Lord of ev[er]y lete within this Realme and the Shirif in his Tourne have auctorite to enquire thereof, and of all the seid defaut[e] and mysdemeanours in his Lete and Tourne.

In later use, a misdemeanor could result in imprisonment, albeit for a lesser period than a felony. The distinction between felonies and misdemeanors in British law was abolished in 1967, but it is retained in the U.S.

An ordinary misdemeanor is not to be confused with a high misdemeanor, which is legal horse of a different color. High misdemeanor is a largely archaic term except for one important context, the impeachment of officers, including the president, and judges of the United States. Article II of the U.S. Constitution states:

The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.

So a high misdemeanor is very serious misconduct, not a minor offense. The phrase appears as early as 1614 when Francis Bacon, serving as attorney general of England and Wales, defined a conspiracy to commit a felony as a high misdemeanor:

Wheresoeuer an offence is capitall or matter of fellony, if it be acted and performed, there the conspiracy, combination, or practise tending to the same offence is punishable as a high misdemeanor, although they neuer were performed.

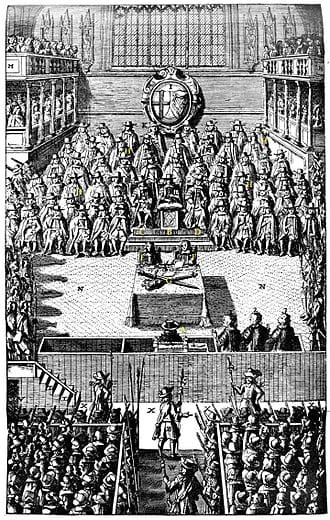

By 1660, high misdemeanor was being used in a political context, to wit the charges that had been leveled against King Charles I in January 1649, the said high misdemeanors being Charles’s crimes that did not amount to the more serious crime of treason. From the account of the 1660 trial of the men charged with his regicide:

That day my Lord, Mr. Cook told the Court that he charged the Prisoner at the bar (meaning the KING) with Treason and high misdemeanors, and desired that the Charge might be read: the Charge was this, That he had upheld a Tyrannical Government &c. and did then press that the prisoner might give an answer to that: and that very earnestly.

Blackstone’s 1769 Commentaries on the Laws of England gives the phrase more definition and notes that high misdemeanors are to be tried in parliament rather than the ordinary courts of law:

II. Misprisions, which are merely positive, are generally denominated contempts or high misdemesnors; of which

1. The first and principal is the mal-administration of such high officers, as are in public trust and employment. This is usually punished by the method of parliamentary impeachment: wherein such penalties, short of death, are inflicted, as to the wisdom of the house of peers shall deem proper; consisting usually of banishment, imprisonment, fines, or perpetual disability.

When writing the U.S. Constitution, the framers were relying on this English legal tradition. The passage regarding impeachment was revised several times, and this gives us today a fairly good idea of what the framers meant by the term high misdemeanor. The original draft included only “treason and bribery” in the list of offenses. George Mason thought this too limiting and suggested the list be replaced by the word “maladministration,” ala Blackstone. But the framers thought that too broad a criterion, which would lead to impeachment for differences over policy and make the president subservient to the Senate. So, Mason suggested the present language, which was accepted. The US Constitution gives the House of Representatives the power to impeach and the Senate the power to try such offenses.

A high misdemeanor does not have to be a crime—the use of the phrase in the Constitution predates the U.S. Criminal Code, so that can’t be what the framers meant. And several federal judges were impeached in the nineteenth century for being intoxicated while on the bench, with the first one being in 1803, when many of the framers were still serving in the House and Senate and presumably understood what they had intended the phrase to mean. Being drunk on the bench is improper behavior, to be sure, but hardly a crime. In the American context, a high misdemeanor is, perhaps, better defined as a violation of the public trust or one’s oath of office. Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist 65, writes of high misdemeanors:

A well-constituted court for the trial of impeachments is an object not more to be desired than difficult to be obtained in a government wholly elective. The subjects of its jurisdiction are those offenses which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust. They are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated POLITICAL, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself. The prosecution of them, for this reason, will seldom fail to agitate the passions of the whole community, and to divide it into parties more or less friendly or inimical to the accused. In many cases it will connect itself with the pre-existing factions, and will enlist all their animosities, partialities, influence, and interest on one side or on the other; and in such cases there will always be the greatest danger that the decision will be regulated more by the comparative strength of parties, than by the real demonstrations of innocence or guilt.

The delicacy and magnitude of a trust which so deeply concerns the political reputation and existence of every man engaged in the administration of public affairs, speak for themselves. The difficulty of placing it rightly, in a government resting entirely on the basis of periodical elections, will as readily be perceived, when it is considered that the most conspicuous characters in it will, from that circumstance, be too often the leaders or the tools of the most cunning or the most numerous faction, and on this account, can hardly be expected to possess the requisite neutrality towards those whose conduct may be the subject of scrutiny.

The convention, it appears, thought the Senate the most fit depositary of this important trust. Those who can best discern the intrinsic difficulty of the thing, will be least hasty in condemning that opinion, and will be most inclined to allow due weight to the arguments which may be supposed to have produced it.

History has borne out Hamilton’s assessment that such trials in a democratic republic would be decided by factionalism rather than actual guilt. Although the conclusion that the Senate would be above such factionalism has proven laughably wrong. There have been four presidential impeachments in US history: Andrew Johnson (1868), Bill Clinton (1998), and Donald Trump (2019 and 2021)—Nixon resigned before the House impeached him. Clinton and Trump were both acquitted because those in their party voted for acquittal. Ten senators of Johnson’s party voted for acquittal, which passed by one vote, but only because they had been bribed with cash and political favors.

Given this history, perhaps then-Representative Gerald Ford was correct when in 1970 he said an impeachable offense, and therefore a high misdemeanor, is “whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers to be at a given moment in history.” Ford, of course, would later become president after Nixon resigned from office.

Sources:

Bacon, Francis. Charge of Sir Francis Bacon Knight, His Maiesties Attourney Generall, Touching Duells. London: Robert Wilson, 1614, 46–47. ProQuest: Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Blackstone, William. Commentaries on the Laws of England, third edition, vol. 4. Dublin: 1770. 121. Gale Primary Sources: Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Ford Gerald. Congressional Record—House, 91st Congress, 2nd Session, vol. 116, part 9, 15 April 1970, 11913.

An Exact and Most Impartial Accompt of the Indictment, Arraignment, Trial, and Judgment (According to Law) of the Twenty Nine Regicides (1660). London, 1679, 142. HathiTrust Digital Library.

Hamilton, Alexander (Publius). “The Fœderalist, No. 64.” New York Packet, 7 March 1788, 2/3. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers. Also, a transcript is available at the Library of Congress. (In its original publication, this paper is numbered Federalist 64. Modern convention accounts it as 65.)

“19 Hen. VII. c. 12.” In The Statutes of the Realm, vol. 2 of 11. London: Dawsons, 1816, 656. HathiTrust Digital Library.

Oxford English Dictionary Online, June 2002, s.v. misdemeanour, n.; misdemeaning, n., misdemean, v.1, misdemeaning, adj.; 1989, s.v. demeanour, n.; demean, v.1.

Rotuli Parliamentorum (Rolls of Parliament), vol. 6 of 6. London: 1767–77, 389. HathiTrust Digital Library.