meltdown / melt / molten

In the public imagination, the noun meltdown is closely associated with nuclear reactor accidents. Given Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukashima, this association is quite understandable. But the word has an older use in metal smelting. And of course, it is also used metaphorically for an emotional breakdown. The history of the word is illustrative of some of the common types of semantic change that words undergo.

At the core of meltdown is the verb to melt. The Present-Day verb comes from two distinct Germanic verbs, one strong and one weak. Strong verbs are those that inflect the tenses through vowel changes, e.g., come/came. Weak verbs inflect through standard suffixes, e.g., look/looks/looked. In Proto-Germanic these two verbs were distinct, but in Old English the two were starting to become confused. Old English had the strong verb meltan, which was originally intransitive—used for things that melted of their own accord but not for those that were melted by some agent—although there are transitive uses of this verb in later Old English. Our Present-Day adjective molten comes from the past participle of this strong verb (note the vowel shift). The second verb was the weak verb meltan/miltan/myltan, which was transitive, that is used for things that were melted by some agent.

The two were already starting to be confused in Old English, but in Middle English the conflation of the two verbs became complete, with the strong and weak inflections used indiscriminately. Gradually, the strong inflections fell away, disappearing by the Early Modern period, although one can occasionally encounter the strong past form molten in later poetry, as opposed to the weak melted.

Meltdown started out as a phrasal verb, melt down, used to refer to the process of smelting metals. We see this phrasal verb in Philip Sydney’s 1591 poem Astrophel and Stella, although Sidney is using the phrasal verb metaphorically:

When sorrow (vsing my owne Siers might)

Melts downe his lead into my boyling brest,

Through that darke Furnace of my heart opprest,

There shines a ioy from thee my onely light

In the twentieth century, the phrasal verb started to be used as a noun phrase, still within the realm of metallurgy. There is this from the Canadian Mining Journal of 2 April 1919:

The Carbon Iron Co., coated the sponge made with lime to retarol [sic, retard] its oxidation in the transfer and during the melt down in the open hearth furnace,—the coating would naturally be put on while the sponge was still on the hearth of the reverbatory.

And by mid-century, the open compound melt down had closed to meltdown. From the Indianapolis News of 26 August 1941:

An underground black market has developed in scarce defense materials. Bootleggers are making something like a national business out of surreptitiously selling metals, particularly aluminum, to small manufacturers on the verge of going out of business for want of raw materials. Fancy prices, usually double the fixed limit, are being extracted. The business has already developed the dark inventive scheming aspects of prohibition law violations—blind offices in large city buildings, actual meltdown of aluminum in small stills known as alley pots, and home smelting.

The nuclear sense is taken from the metallurgical one and dates to the early days of nuclear power. From the Washington Post of 24 March 1956:

To date, there have been only two reactor accidents reported anyway.

One in 1952 was at Canada’s Chalk River plate where a mechanical failure caused a meltdown of the uranium fuel and subsequent radioactive contamination of water and heavy water components.

So far, Philip Sidney aside, meltdown has remained in the technical realm of metals, including uranium in the cores of nuclear plants. But the 1979 reactor accident at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania would inject the word into the daily news cycle and on the lips of just about everyone in America. And it was this event that created the opportunity for extending the word into the emotional realm. People, as well as nuclear reactors, could have meltdowns. Here is a nice example from the Christian Science Monitor of 30 June 1980:

Messy rooms and teen-agers seem to be an unavoidable combination. […] The subject creates a lot of tension. And the other day David told me if I said one more word about it he would have a meltdown. And again I laughed. And, of course, the laughter is marvelous. It clears the air.

Sources:

Bosworth, Joseph and T. Northcote Toller. An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, with Supplement. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1898 and 1921, s.v. meltan, v., miltan, v. Bosworth Toller’s Anglo-Saxon Dictionary Online.

Goldsand Freund, Roz. “Laughter Clears the Air Until He Cleans Up His Room.” Christian Science Monitor, 30 June 1980, 14/3. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Mallon, Paul. “News Behind the News.” Indianapolis News, 26 August 1941, 7/5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Moffatt, James W. “A New Method for the Smelting of Iron Ores.” Canadian Mining Journal, 40.13, 2 April 1919, 208/1. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2001, s.v. melt, v.1, meltdown, n.; September 2002, s.v. molten, adj.

Sidney, Philip. Syr P.S. His Astrophel and Stella. London, Thomas Newman, 1591, 45. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Unna, Warren. “A-Reactor Insurance.” Washington Post, 24 March 1956, 15/2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

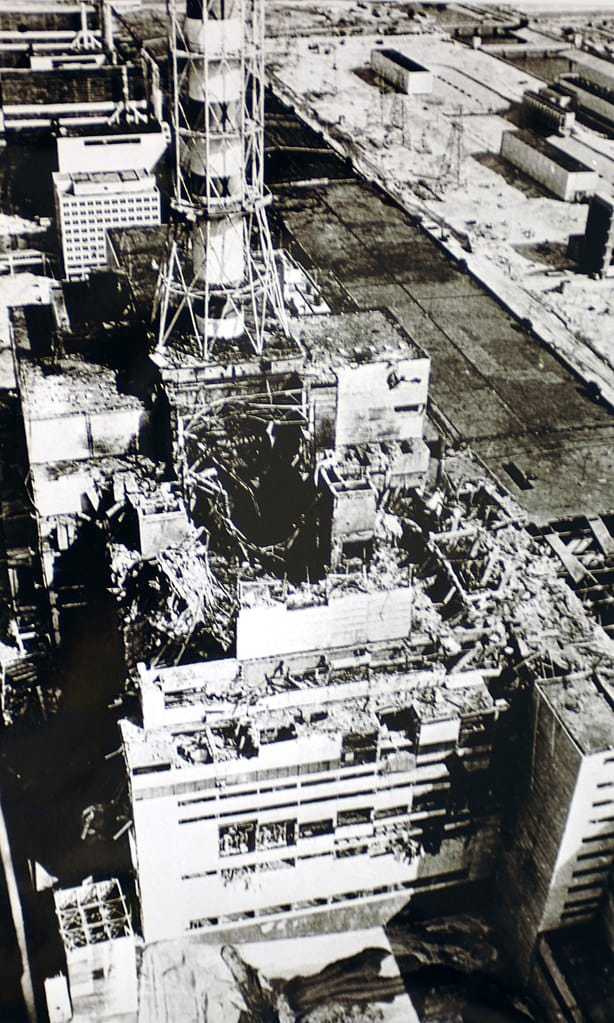

Photo credit: Unknown photographer, 1986. Ukrainian Society for Friendship and Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (USFCRFC). IAEA ImageBank (Flickr). Used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.