literally

Literally is often the target of grammar scolds and pedants. What the scolds are carping on is the figurative use of the word, as in, I was literally glued to my seat. The word literally comes to us, via French, from the Latin literalis, meaning pertaining to letters. It literally means word for word, actually, exactly. But when someone says they were literally glued to their seat, it is a pretty good bet that they are not actually attached to a chair with some sort of mucilage, and it is this non-literal use of literally that the pedants and scolds object to.

What the pedants and scolds fail to realize is that words can have multiple meanings. Furthermore, it’s hardly unknown to have words that have two contradictory meanings, such as the noun sanction (meaning both permit and punish) and the verb to cleave (to separate and to join together). Usually which meaning is intended is obvious from the context, as in someone being literally glued to their seat. Such multiple meanings are rarely the source of confusion.

The pedants and scolds also fail to realize that this figurative sense of literally has been around for a lot longer than they think—over two centuries. And it has been employed by writers who are a lot better at using the English language than they are.

Literally dates back to Middle English, appearing around 1429 in a work titled The Mirour of Mans Saluacion:

Litteraly haf ȝe herde this dreme and what it ment,

Now lyes moreovre to knawe þerof the mistik intent.

(Literally have you heard this dream and what it meant,

Now lies moreover to know thereof the mystic intent.)

This early use is, of course, is not figurative. But by the late seventeenth century, writers were beginning to use literally as an intensifier, but only for true statements. In 1670, Edward Hyde, the First Earl of Clarendon wrote of the interpretation of vow of poverty taken by Capuchin monks compared to that of the Benedictines and Jesuits:

The other poor men literally affect Poverty in the highest Degree that Life can be preserved, with what uneasiness soever, insomuch as it is not lawful for them to provide or retain what may be necessary for to Morrow, nor to have two Habits nor two Pair of Shoes.

Within a hundred years, however, literally was being put to use to intensify things that weren’t true. In 1769 Frances Brooke wrote in her novel The History of Emily Montague:

He is a fortunate man to be introduced to such a party of fine women at his arrival; it is literally to feed among the lilies.

Brooke is quoting the Song of Solomon 4:5:

Thy two breasts are like two young roes that are twins, which feed among the lilies.

Brooke may be using the word to mean “I quote word for word” or “I am making a literary reference,” but she is also employing metaphor, so her use occupies something of a middle ground between the actual and the figurative. And by 1801 the figurative use was being employed without reservation. Joseph Dennie’s satiric The Spirit of the Farmer’s Museum and Lay Preacher’s Gazette had this to say about beaus, what we might call “metrosexuals” today:

BEAU.

A being, who would puzzle Linnæus to ascertain the class to which he belonged. Beaus have generally been arranged among the monkey tribe. This was extremely hard upon the monkeys; for they are tolerably agreeable and sprightly animals, but a beau is as stupid in conversation, as he is frivolous in dress. His is like Miss Fanny Williams’s preserver of beauty, “a curious compound.” He is, literally, made up of marechal powder, cravat and bootees. The tailor and the shoemaker, the perfumer, and the laundress, must all fit in council, before a beau can take any public steps.

And by 1838–39, actress Fanny Kemble could, upon visiting her husband’s Georgia plantations for the first time, muse about the effects of her giving up a successful career on the stage to marry a Southern slave owner:

And then the great power and privilege I had foregone of earning money by my own labor occurred to me, and I think, for the first time in my life, my past profession assumed an aspect that arrested my thoughts most seriously. For the last four years of my life that preceded my marriage I literally coined money, and never until this moment, I think, did I reflect on the great means of good, to myself and others, that I so gladly agreed to give up forever for a maintenance by the unpaid labor of slaves—people toiling not only unpaid, but under the bitter conditions the bare contemplation of which was then wringing my heart.

Nor has the figurative use of literally been employed only by hacks, humorists, and actresses. For example:

“Lift him out,” said Squeers, after he had literally feasted his eyes in silence upon the culprit.

—Charles Dickens, Nicholas Nickleby, 1839

Tom was literally rolling in wealth.

—Mark Twain, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, 1876

Lily, the caretaker’s daughter, was literally run off her feet.

—James Joyce, “The Dead,” Dubliners, 1914

And with his eyes he literally scoured the corners of the cell.

—Vladimir Nabokov, Invitation to a Beheading, 1960

Of course, just because the usage isn’t wrong doesn’t mean that all the uses of it are good ones. Like any form of hyperbole, the figurative literally can be overused. And care should be taken that it doesn’t cause confusion. Its use is not appropriate for all genres. For instance, it is probably a bad idea to employ it in expository prose, such as an academic paper. But in fiction, in informal prose, and in speech there is nothing wrong its judicious use. So, unless you’re a better writer than Dickens, Twain, Joyce, and Nabokov, don’t go around saying that the figurative and intensifying use of literally is wrong altogether.

Discuss this post

Sources:

Baron, Dennis. “Literally Has Always Been Figurative.” The Web of Language (blog), 23 August 2013.

Brooke, Frances. The History of Emily Montague, vol. 4 of 4. London: J. Dodsley, 1769, 175. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Dennie, Joseph. The Spirit of the Farmer’s Museum and Lay Preacher’s Gazette. Walpole, New Hampshire: D. & T. Carlisle for Thomas & Thomas, 1801, 261–62. Gale Primary Sources: Sabin Americana.

Henry, Avril, ed. The Mirour of Mans Saluacion. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1987, 51, lines 553–54. Archive.org.

Hyde, Edward, First Earl of Clarendon. “On an Active and on a Contemplative Life” (1670). In A Collection of Several Tracts. London: T. Woodward and J. Peele, 1727, 170. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Kemble, Frances Anne. Journal of Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838–39. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1863, 104–05. Gale Primary Sources: Nineteenth Century Collections Online.

Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage. Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster, 1994, s.v. literally.

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. literalli, adv.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, September 2011, s.v. literally, adv.

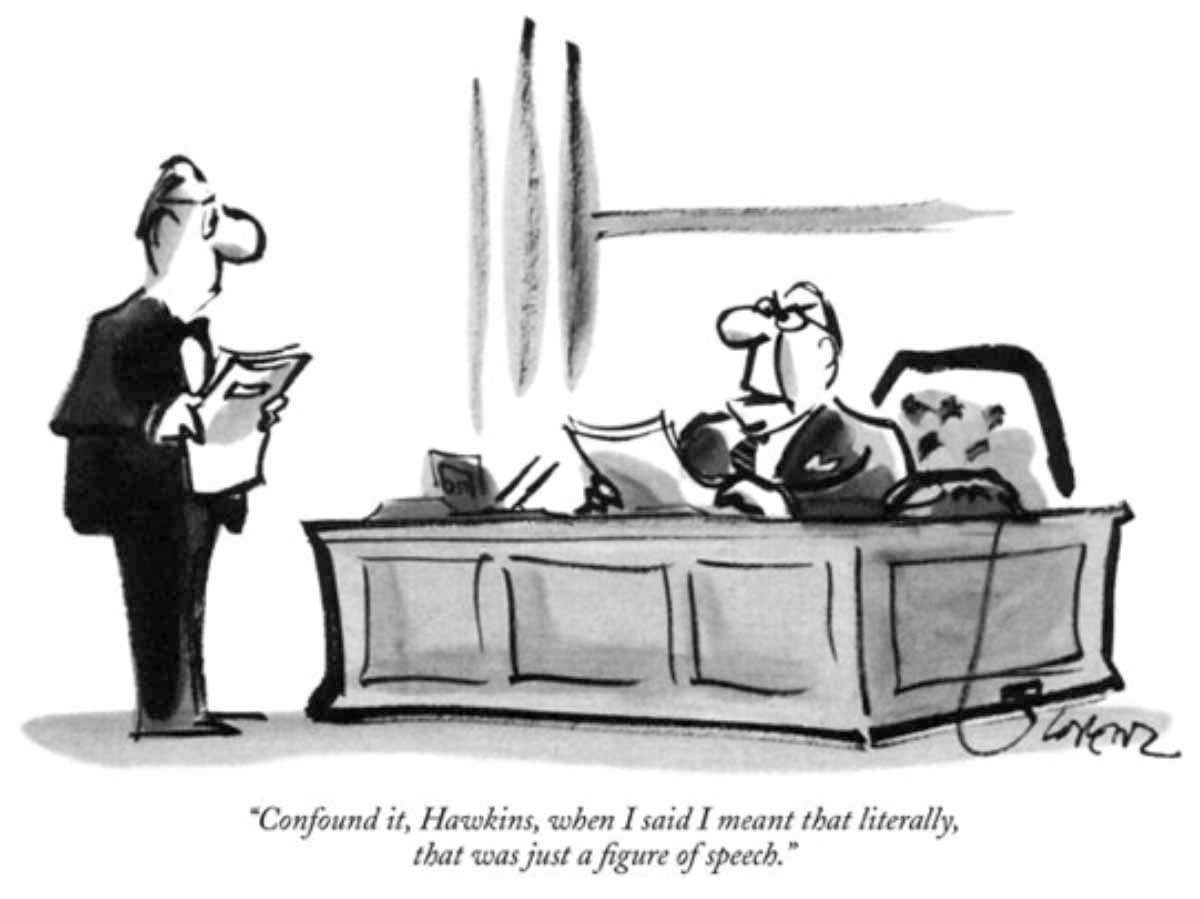

Image credit: Lee Lorenz, 1977. Fair use of a low-resolution version of a copyrighted image to illustrate the topic under discussion.