libel

In present day legal parlance, according to Black’s Law Dictionary, a libel is “a defamatory statement expressed in a fixed medium, esp. writing but also a picture, sign, or electronic broadcast.” It is also a verb meaning “to defame (someone) in a permanent medium, esp. in writing.”

The word comes from the Anglo-Norman libel, meaning a legal writ or complaint, which is from the Latin libellus, or little book. It makes it’s English appearance by the end of the thirteenth century, when it appears in The Metrical Chronicle of Robert of Gloucester describing events of a century earlier, during the reign of King John:

& after sein Micheles day · þe þridde day he com ·

To douere & þe bissop · of londone wiþ him nom ·

& þe bissop of eli · & þe king sone wende ·

To a maner þer biside · & to hom anon sende ·

Is heye Iustice of is lond · sir · G · le fiȝ peris ·

Þat ȝuf þe erchebissop · oþer eni of his ·

Wolde eni þing · toward him · þat hii sende him libel ·

& esste ek articles · þat nere noȝt to graunti wel ·

Ac vor it nas bote al þe mase · þe erchebissop sone ·

Wende aȝen ouer se · as best was to done ·

[And on the third day after Saint Michael’s day, he (i.e., the archbishop) came to Dover and brought with him the Bishop of London and the Bishop of Ely, and the king soon went to a nearby manor and soon sent for them. Sir Geoffrey le Fitz Piers is the Chief Justiciar of this land, and that if the archbishop or any of his would have anything with respect to him, that they send him a libel and asked also for items that were not to be granted.]

By the late fourteenth century and probably under the influence of the Latin, libel was being used to mean a small book or short treatise. And by the early sixteenth century, the word was being used to denote a printed and publicly distributed leaflet or pamphlet. Such leaflets were often defamatory and dubbed libellus famosus or famous libels, the famous referring to the fact that they were published and distributed. Here is an early example from a 26 June 1521 letter written by John Longland, the bishop of London, to Cardinal Wolsey about a pair of heretic priests in his diocese:

And noo doubte ther arre moo in Oxenford as apperith by suche famous lybells and bills as be sett uppe in night tymes upon Chirche doores. I have twoo of them, and delyvered the third to my Lord of London. I truste your Grace hath seen itt, whereby ye may perceyve the corrupt mynds.

And by the early seventeenth century libel had acquired its present-day legal definition of a written defamatory statement, as opposed to a slander, which is a spoken defamatory statement. At around the same time, the verb to libel, meaning to make such a defamatory statement, also made its appearance.

Sources:

Garner, Bryan A., ed. Black’s Law Dictionary, 11th edition, 2019, s.v. libel, n., libel, v. Thomson Reuters Westlaw.

Longland, John, Bishop of Lincoln. Letter to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, 26 June 1521. In Henry Ellis, ed. Original Letters Illustrative of English History, third series, vol. 1 of 4. London: Richard Bentley, 1846, 253. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. libel(le, n.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. libel, n., libel v.

Wright, William Aldis, ed. The Metrical Chronicle of Robert of Gloucester, vol. 2 of 2. London: Stationary Office, 1887, lines 10,227–237, 703. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

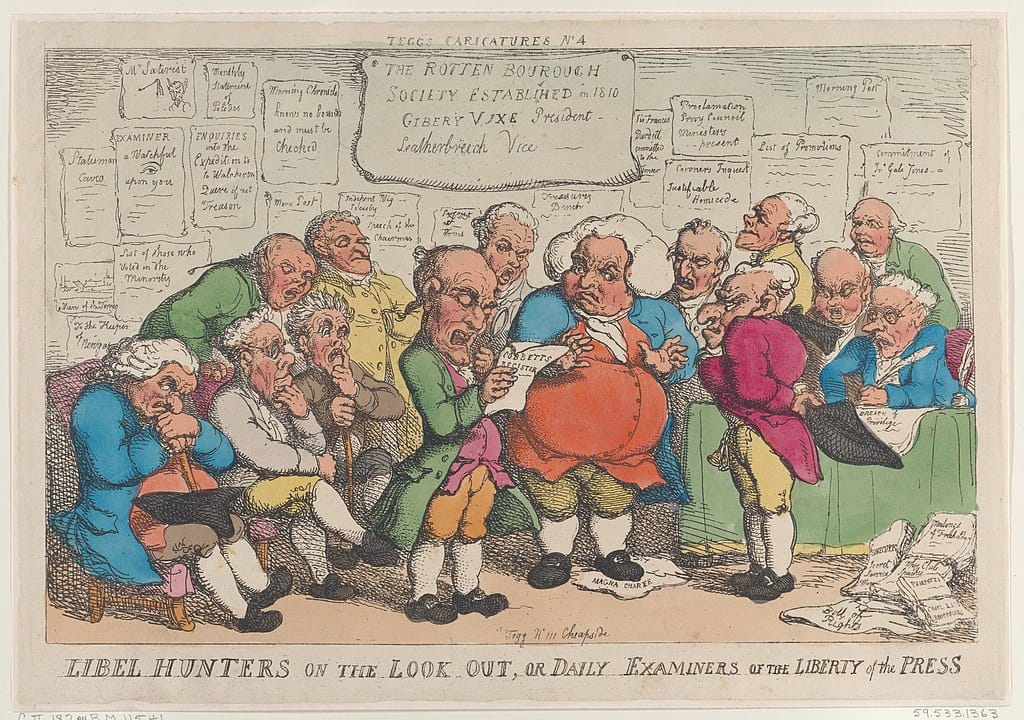

Image credit: Thomas Rowlandson, 1810. Wikimedia Commons. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Public domain image.