leap-year

The necessity for adding a day to the calendar every four years is due to the fact that the Earth’s orbit of the sun is not exactly 365 days; it’s closer to 365.25 days. Therefore, about every four years we add one day to the calendar to keep the seasons aligned with the calendar. The practice of adding intercalary days began with the Romans and was revised to the current practice of adding in intercalary day to February every four years began with the Julian calendar instituted under the reign of Julius Caesar.

But because the year is not exactly 365.25 days long, the Gregorian calendar, first instituted in 1582, which we use today, does not add an intercalary day in years that are evenly divisible by 100, unless that year is also evenly divisible by 400. So 1900 was not a leap year, but 2000 was.

Furthermore, because the earth’s rotation is not exactly twenty-four hours long—it varies irregularly—since 1972, a leap second has been occasionally added to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) to keep the days in line with the earth’s rotation. Most people don’t notice when a leap second is added.

The use of leap to denote calendrical shifts like this goes back to Old English. Ðæs monan hlyp (the leap of the moon) appears in Ælfric of Eynsham’s De temporibus anni, written c. 993. Ælfric was a Benedictine monk who is widely regarded as the chief prose stylist of the late Old English period. De temporibus anni is his attempt to provide monks and priests with a text on astronomy and the calendar that they could use to educate themselves and the laity and in combating superstition and myth. Ælfric used hylp in reference to the moon (which needs a day added to its orbit of the earth about every 19 years):

Swa swa þære sunnanb csleacnys acenðc ænne dæg 7 aned niht æfre ymbe feower gear, swa eac þæs monan eswyftnys awyrpðe ut ænne dæg 7 ane niht of ðam getele his rynes æfre embe nigontyne gear, 7 se dæg is gehaten saltus lune, þæt is ðæs monan hlyp, forðan ðe he oferhlypð ænne dæg, 7 swa near þam nigonteoðanf geare swa bið se niwag mona braddra gesewen.

(Just as the sun’s slowness always produces one extra day and night after four years, so also the swiftness of the moon throws out one day and night from the reckoning of its course after every nineteen years, and that day is called saltus lunae, that is the moon’s leap, because it leaps over one day, and the nearer to the nineteenth year, the wider is the new moon seen.)

The use of the phrase leap year itself is recorded by 1387, when it appears in John Trevisa’s translation of Ranulf Higden’s Polychronicon:

Þat tyme Iulius amended þe kalender, and fonde þe cause of þe lepe ȝere. Þe Romaynes, as [the] Hebrewes bygone here ȝeres in Marche anon to Numa Pompilius his tyme, and þis Numa putte Ianvier and Feverer to the ȝere in an uncerteyn manere, but þe ȝere was not ful amended to fore Iulius his tyme.

(In that time, Julus amended the calendar and invented the concept of the leap year. The Romans began their years in March, as did the Hebrews, until Numa Pompilius’s time, and this Numa inserted January and February into the year in an uncertain manner, but the year was not fully corrected before Julius’s time.)

But there is good reason to believe that the phrase leap year was in use in Old English, even though it doesn’t appear in the extant Old English corpus. The term hlaup-ár, or leap year, is recorded in Old Norse, and most Norse calendrical terms were borrowed from Old English. So it seems likely that Norse acquired this one from Old English too.

Sources:

Ælfric. Ælfric’s De temporibus anni. Martin Blake, ed. and trans. Cambridge, UK: D.S. Brewer, 2009, 90–91. JSTOR.

Dictionary of Old English: A to I, 2018, s.v. hylp, n.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. leap year, n.

Trevisa, John. Polychronicon Ranulphi Higden, vol. 4 of 9. Joseph Rawson Lumby, ed. London: Longman and Trübner, 1872, 199. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

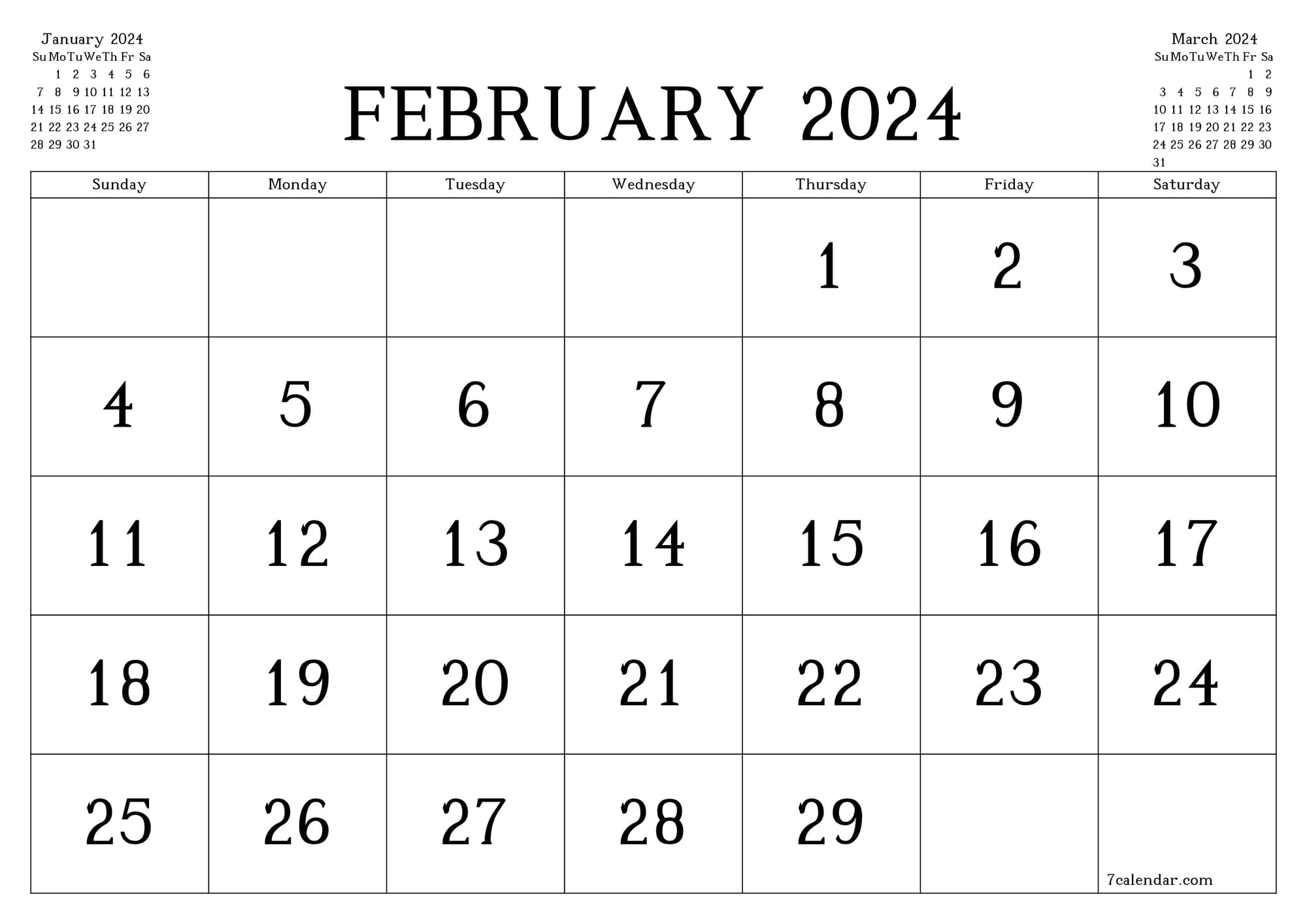

Image credit: 7.calendar.com, accessed 24 January 2024. Used under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.