hot dog

Hot dog has two primary meanings, that of a sausage and that of a person who is superior or expert, especially boastfully so. Both started as American slang in the 1890s, with one, the sausage, eventually moving into standard English. But despite these similarities, the two senses are etymologically unrelated.

The sausage sense comes from the idea that dog meat is used in making the sausages. The idea that sausages are made from various unsavory ingredients is an ancient one, but here are two more proximate examples from nineteenth-century America. The first is an account of a Cockney tourist in New Orleans swearing out a complaint against a sausage vendor that appeared in the Weekly Picayune of 24 May 1841:

“Vy you see, ven I landed from sea I felt like eating a sausenger, or summit nice, and I goes to this ’ere man’s shop, and I says—‘I vants a pund o’ saussengers, but they must be a wery shuperior article. You can’t come cats’ meat over me, ’case I’s Hinglish myself.’ Vit that he gets offended, and says, ‘Ve haint cockneys, old feller; ve doesn’t go that rig.’ Velll, I buy’s ’em, and ven I takes ’em home they all laughs and says, ‘That ’ere’s a reg’lar suck!’ and I asked them vat they means, and they says, ‘Vy bless your hinnocent heyes! haven't you heard of the dog law?’ Vi’ that, your vuship, my suspicions became aroused—I hexamined the harticle, and I’m blow’d if I didn’t find one of the saussengers vos a dog’s tail, hair and all!”

[…]

The cockney expressed his determination to expose the whole transaction in his book of travels, and drawing out his diary he wrote as follows:—

“Mem.—New Orleans is a wery wile, wicious place: they kills men there with Bowie-knives and dogs with pisoned sassengers. They berries the former holesale in the swamp, and retails the latter, tails and all, as sassenger meat. It’s a ’orrible state of society!”

According to the paper, the complaint was dismissed as not being a criminal matter, and the tourist was told he was free to pursue a civil suit. The story is, in all likelihood, a fiction invented by the newspaper’s editors, but it does contain a truth about the public’s apprehension about what goes into those sausage casings.

The second actually uses the noun dog to refer to a sausage. From the Louisville, Kentucky Courier-Journal of 30 October 1881:

“Hot sau-sage! Hot sau-sage! Sau-sa-ges! Tak’ a sausage. All hot!

“Here’s the dog man,” said one of a group of men who were clustered, a night or two ago, round the refreshment counter of a late-closing restaurant in search of a nightcap. “Who’ll have a dog?”

“Nein, not dog. Clean, nice, made of de best ox and pig and little calf which dies. It is already 1 of de clock in de morning. I must sell mine sausage or not have breakfast. Tak’ a sausage? Only five cents!”

We see the phrase hot dog used to refer to sausage meat in Indiana’s Evansville Daily Courier of 14 September 1884. The context is that of saloonkeepers encouraging over-vigorous enforcement of temperance laws to the point that non-alcohol-related businesses would be adversely affected, thereby creating a backlash to the laws. Note that here hot dog is being used as a mass noun for the meat, not for individual sausages:

The line has been drawn upon the saloon only, however, and they, the saloon-keepers, are taking steps toward the dernier resort, (excuse my French,) which had to be taken at Evansville some time ago, as I have heard, i[n] regard to stopping all commercial pursuits that do not come within the pale of necessity. I learn that last night they had spies on the Pioneer Press and Tribune buildings, and they will aid the city government and Y.M.C.A. in enforcing the law to the limit. Even the innocent “wienerworst” man will be barred from dispensing hot dog on the street corner. This of course, is for the purpose of making the city ordinance regarding the patrol district and Sunday enforcement obnoxious.

Finally, we see hot dog used to refer to individual sausages on buns in New Jersey’s Paterson Daily Press of 31 December 1892:

A new adjunct to the sport [i.e., ice skating] is the Wiener wurst man with his kettle of steaming hot sausages and rolls. The he retails at a nickel, and his a very popular individual with the throng, for the sport soon creates an aching void that nothing but substantials will fill, and somehow or other a frankfurter and a roll seem to go right to the spot where the void is felt the most. The small boy has got on such familiar terms with this sort of lunch that he now refers to it as “hot dog.” “Hey, Mister, give me a hot dog quick,” was the startling order that a rosy-cheeked gamin hurled at the man as a Press reporter stood close by last night. The “hot dog” was quickly inserted in a gash in a roll, a dash of mustard also splashed on to the “dog” with a piece of whittled stick, and the order was fulfilled. The gamin had hardly dropped a nickel into the man’s hand before he was skimming off to join his companions. This proceeding was repeated time and again, and the “hot dog” man must be getting rich.

Various false etymologies for the origin of this sense of hot dog have been promulgated over the years. Perhaps the most persistent one concerns sausage vendor Harry Stevens, cartoonist T.A. “Tad” Dorgan, and the famed Polo Grounds of New York. According to the myth, c.1900 Stevens was selling the new type of snack at a New York Giants game. Dorgan recorded the event in a cartoon, labeling the sausages “hot dogs” because he didn’t know how to spell “frankfurter.” Other variants have Stevens naming the delicacy and Dorgan recording it. Unfortunately, the dates don’t work; the 1900 date for the incident at the Polo Grounds is after the term was coined. Also no one has found the Dorgan cartoon in question. There is a 1906 Dorgan cartoon featuring hot dogs at a sporting event, but besides being even later, it is a reference to a bicycle race at Madison Square Garden, not a baseball game at the Polo Grounds.

The second sense of hot dog has an entirely different origin unrelated to sausages or even food.

Dog has been used as a slang term for a person since the fourteenth century, usually in a pejorative sense. But in the late sixteenth century we begin to see uses of dog referring to a person in a sympathetic or affectionate manner. But it isn’t until the closing years of the nineteenth century that we see hot dog used to refer to a person. This use in the 18 October 1894 issue of the Wrinkle, the University of Michigan’s literary magazine, uses the phrase to refer to a man who on the surface would appear to be a desirable prospect in a fraternity’s rush, or membership drive:

A Suit of Clothes, great wonders wrought.

Two Greeks a “hot dog” freshman sought.

The Clothes they found, their favor bought.

A prize! The foxy rushers thought.

Who’s Caught?

And again from the University of Michigan, we see the term defined in a January 1896 glossary of student slang:

hot-dog. Good, superior. “He has made some hot-dog drawings for ——.”

We see this sense of hot dog outside of a collegiate context in humorist William Kountz’s 1899 Billy Baxter’s Letters:

When I came up the subject was Du Bois’ Messe de Mariage. (Spelling not guaranteed.) I asked about it this morning Jim. A Messe de Mariage seems to some kind of wedding march, and bishop who is a real hot dog won’t issue a certificate unless the band plays the Messe.

Another humorist, this time George Ade, uses it to describe an expert professional gambler in his 1904 Breaking Into Society:

After Herbert had signed up all the checks and put a Cold Towel on his Head, he began to Roar somewhat and talk about chopping on the all-night Seances.

“You must not Beef,” said Cousin Jim. “A True Sport never lets on, even when they unbutton his Shoes.”

“Do you know, I sometimes suspect that I am not qualified to be a Hot Dog,” said Herbert. “I find that I begin to pass away about 2 A.M. Perhaps it is owing to some Oversight in my Early Training, but I notice that after I have taken a thousand Drinks I cannot put the Red Ball into the Corner Pocket. I have a Timid Nature, and somehow I cannot learn to whoop the Edge on a Pair of Nines. I’m afraid that I drank too much Rain-Water in my Youth. And, besides, I got into the Habit of going to bed.”

The verb, meaning to boastfully show off, dates to at least 1959.

So that’s how two phrases with much in common have startling different origins.

Sources:

Ade, George. Breaking Into Society. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1904, 184. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Cohen, Gerald Leonard, Barry A. Popik, and David Shulman, Origin of the Term “Hot Dog” (Rolla, Mo.: Gerald Cohen, 2004)

Gore, Willard C. “Student Slang.” The Inlander (University of Michigan), 6.4, January 1896, 145–55 at 148. Google Books.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, n.d., s.v. hot dog, n.1., hot dog, n.2.

Kountz, William J. “In Society” (1 February 1899). Billy Baxter’s Letters. Harmarville, Pennsylvania: Duquesne Distributing, 1899, 34. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

“On the Flashing Steel.” Paterson Daily Press (New Jersey), 31 December 1892, 1/7 & 5/2. Google News.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, December 2008, s.v. hot dog, n., adj. & int., hot dog, v.

“A Sausage Man’s Tale.” Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), 30 October 1881, 8/4. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

“A Tourist in Trouble.” Weekly Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana), 24 May 1841, 1/4. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“A Very Dry Letter.” Evansville Daily Courier (Indiana), 14 September 1884, 2/5. Newspapers.com.

Wrinkle (University of Michigan), 2.1, 18 October 1894, cover page. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

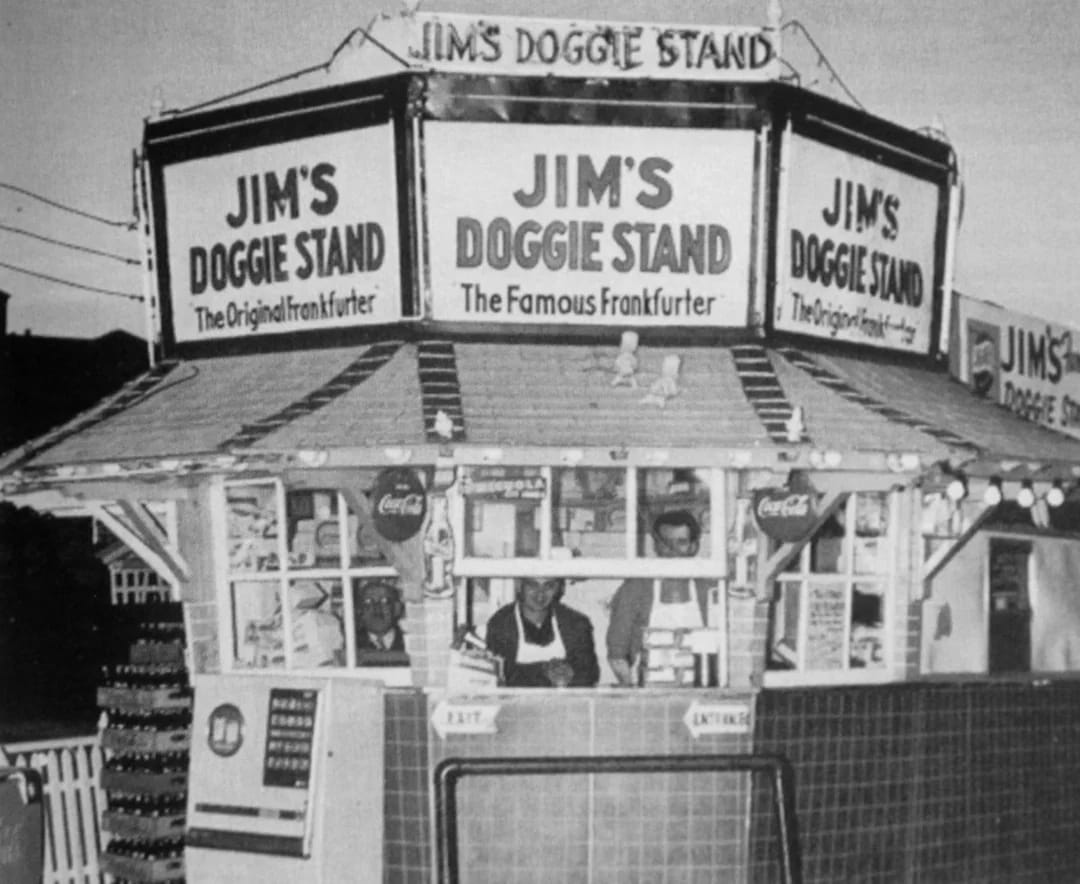

Image: unknown photographer, c. 1961, Reddit.com. Fair use of a copyrighted image from unidentifiable source used to illustrate the topic under discussion.