heaven / seventh heaven (paid)

The word heaven can be traced to the Proto-Germanic root *hemina- / *hemna-. That root gives us the Old English heofon, which is cognate with the Old Saxon heƀan, the Old Icelandic himinn, and the Old High German himil, among others. Going further back, the exact connection to Proto-Indo-European is muddy and uncertain, but it may be from a root something like *ke-men.

The basic meanings of the word that we still use today were mostly present in Old English. The use of heaven to mean the sky or firmament in which the celestial objects move can be seen in Beowulf, line 1571, when Beowulf first sees the sword that he will use to kill Grendel’s mother; the light shining from the sword is compared to the sun in the sky:

Lixte se leoma, leoht inne stod,

efne swa of hefene hadre scineð

rodores candel.

(The radiance gleamed, the light stood within, as from heaven, the sky’s candle clearly shines)

That’s heaven in the singular, but the use of the plural to mean the same thing can be seen in an Old English gloss on Psalm 8 found in the Vespasian Psalter. The Latin psalter was copied in the second quarter of the eighth century, and the Old English gloss added in the early ninth:

for ðon ic gesie heofenas werc fingra ðinra monan & steorran ða ðu gesteaðulades.

quoniam uidebo caelos opera digitorum tuorum, lunam et stellas quas tu fundasti

(for I see the heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars which you have created)

We see heaven used to mean the abode of God in Cynewulf’s poem Elene. Elene, or Helena, was the mother of Emperor Constantine, who led a pilgrimage to the Holy Land to find the True Cross:

Sie þara manna gehwam

behliden helle duru, heofones ontyned,

ece geopenad engla rice,

dream unhwilen, ond hira dæl scired

mid Marian, þe on gemynd nime

þære deorestan dæg-weorðunga

rode under roderum, þa se ricesða

ealles ofer-wealdend earme beþeahte.

(For every one of those who commemorate the feast-day of most beloved cross under the skies that the mightiest Overlord took into his arms may the door of hell be closed, the heavens revealed, the kingdom of angels eternally opened, joy everlasting, and their part decreed by Mary.)

In Old English, heaven could also be used to refer to the abode of non-Christian gods. We see this in the translation of Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, which dates to the late ninth century:

ðu geherdest oft reccan on ealdum leasum spellum þætte Iob Saturnes sunu sceolde beon se hehsta god ofer ealle oðre godas, and he scelde bion þæs heofenes sunu and scolde ricsian on heofenu.

(You have often heard tell in old false stories that Jove, the son of Saturn, was supposed to be the highest god over all the other gods, and he was supposed to be the son of heaven and supposed to rule in the heavens.)

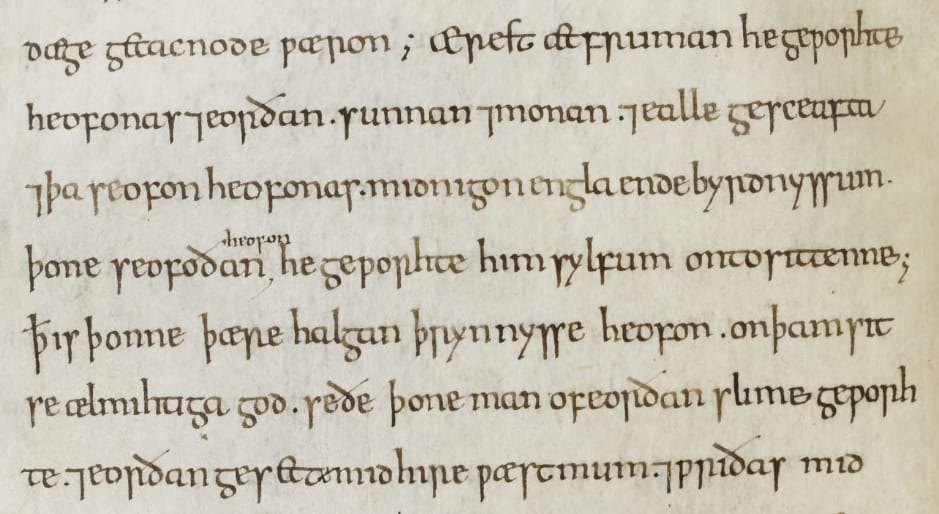

The phrase seventh heaven, or more accurately seofoðan heofon, also dates to Old English. Heaven, according to the Talmud, is divided into seven parts, with the seventh being the abode of God. The idea of seven probably arises out of a connection with the seven “planets” of the ancients (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the moon, and the sun; cf. planet). This idea carried over into Islam and is referred to in the Qur’an and in the Hadith, as well as into Christian tradition, although the concept doesn’t appear in the Christian Bible. We can see this Old English use of seventh heaven in an early eleventh-century homily for Easter Sunday:

Ærest, æt fruman, he geworhte heofonas & eorðan, sunnan & monan, & ealle gesceafta, & þa seofon heofonas mid nigon engla endebyrdnyssum. Þone seofoðan heofon he geworhte him sylfum on to sittenne. Þ[æt] is þonne þære halgan þrynnysse heofon.on þam sit se ælmihtiga God, se ðe þone man of eorðan slime geworhte.

(First, at the beginning, he created the heavens & the earth, the sun & the moon, & all creation, & the seven heavens with nine orders of agnels. The seventh heaven he created for himself to abide in. That is therefore the heaven of holy Trinity in which abides the almighty God, he who created man from earthly slime.)

But extended uses of heaven come somewhat later. The use to mean a state of bliss dates to the Middle English period, and we see that sense in Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde:

This yard was large, and rayled alle th’aleyes,

And shadewed wel with blosmy bowes grene,

And benched newe, and sonded alle the weyes,

In which she walketh arm in arm bitwene,

Til at the laste Antigone the shene

Gan on a Troian song to singen cleere,

That it an heven was hire vois to here.

(The garden was large, and all the paths fenced and well shaded with blossomy green boughs, and newly provided with benches, and all the paths sanded, in which walked arm in arm between, till at last Antigone the bright began to sing a Trojan song clearly, so that it was a heaven to hear her voice.)

And we see seventh heaven used to mean a state of bliss by the late eighteenth century. Here is an example from a 1786 anecdote about the late writer Henry Fielding:

The invitation was accepted—the viands were spread—the exhilarating juice appeared—and cares were given to the winds. The moments flew joyous, and unperceived; they both partook largely of “the feast of reason, and the flow of soul.” In the course of their tête-à-tête, Fielding became acquainted with the state of his friend’s pocket. He emptied his own into it; and parted, a few periods before Aurora’s appearance, greater and happier than a monarch. Arrived at home, his sister, who waited his coming with the greatest anxiety, began to question him as to his cause for staying. Harry began to relate the felicitous rencontre—his sister Amelia tells him, the Collector had called for the taxes twice that day. This information let our worthy author down to earth again, after his elevation, in his own reflections, to the seventh heaven. His reply was laconic, but memorable: “Friendship has called for the money, and had it:—let the Collector call again.”

Nothing can bring one down to earth faster than a visit from the tax man.

Sources:

American Heritage Dictionary Indo-European Roots Appendix, 2022, s.v. ak-.

Boethius. The Old English Boethius, vol. 1 of 2. Malcolm Godden and Susan Irvine, eds. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009, B-text, 35.117–19, 333. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 180, fol. 61v.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. Troilus and Criseyde, in The Riverside Chaucer, third edition. Larry D. Benson, ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987, 2.820–26, 500.

Cynewulf. Elene, in The Old English Poems of Cynewulf. Robert E. Bjork, ed. Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 23. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2013, lines 1228a–35, 228.

Dictionary of Old English: A to Le, 2024, s.v. heofone, heofone, n.

Fulk, R. D., Robert E. Bjork, and John D. Niles. Klaeber’s Beowulf, fourth edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008, lines 1570–72a, 54.

G. S. “Anecdote of the late Harry Fielding.” Scots Magazine, June 1786, 297. Gale Primary Sources: British Library Newspapers.

Kroonen, Guus. Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic, vol. 2. Leiden: Brill, 2013, 220. Archive.org.

Kuhn, Sherman M., ed. The Vespasian Psalter. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1965, Psalms 8, 5. Archive.org. London, British Library, Cotton MS Vespasian A.i.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2008, s.v. heaven, n.; March 2021, s.v. seventh heaven, n.

Schaefer, Kenneth Gordon. An Edition of Five Old English Homilies for Palm Sunday, Holy Saturday, and Easter Sunday (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1972), 175. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, 7525717. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 162, 384. Parker on the Web.

Photo credit: Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 162, 384. Parker on the Web. Used under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial 4.0 International license.