gremlin

A gremlin is a mythical creature of the upper air who causes damage to airplanes. The term starts appearing in Royal Air Force slang during the interwar years. There are claims that gremlin was in use during the First World War, but while this claim is plausible, and perhaps even probable, no evidence of use that early has surfaced. The origin of the term is unknown.

What is known is that gremlin, as first recorded, originally had a different meaning, that of a low-ranking commissioned or non-commissioned air force officer, one who performed the routine duties that were beneath the dignity of the brass. We see this sense in a poem, titled Flight-Lieutenant Hiawatha, that appeared in the 10 April 1929 issue of the journal Aeroplane, a poem which opens:

Should you ask me way this morning,

Whence this grumbling and this grousing,

Whence these wild reverberations

I should answer, I should tell you:

Why the chaps are discontented.

In His Majesty’s Royal Air Force

There are many ranks and noble

Wing Commanders, fair and pleasant;

Captains of the Group most mighty,

Air Vice-Marshals, Squadron Leaders;

Squadron Leaders with their boots on.

Sergeant-Majors wise and canny,

Full of beer and work-shy methods.

There is a class abhorréd,

Loathed by all the high and mighty,

Slaves who work and get but little,

Little thanks for all their labour;

Yet they are both skilled and many,

Many men with many talents.

They are those below the rank of

Down below the Squadron Leader;

They are but a herd of gremlins,

Gremlins who do all the flying,

Gremlins who do much instructing,

Work shunned by the Wing Commanders,

Work both trying and unpleasant.

In among this herd of gremlins

Some there are with many medals

And with years of hard war service.

Some were captives down in Hunland,

Some are old and very senior,

Senior to some squadron leaders,

Squadron Leaders with their boots on.

These are called the Flight Lieutenants,

Gremlins old and very senior.

The poem is largely a complaint of the RAF’s use of the phrase “All Officers below the rank of Squadron Leader” (and the low pay of those who are so referred) which the poet thinks is demeaning to those experienced airmen who do most of the flying and work of the air force. Also of note is the use of grumbling and grousing in the opening lines, which alliterates with gremlin. Whether the poet was simply making a poetic flourish or whether gremlin was coined with grumbling and grousing in mind cannot be determined.

The sense of the mythical creature is recorded about a decade later. From Pauline Gower’s 1938 book Women with Wings:

Country that was particularly high or enveloped in cloud became known among the pilots as Gremlin country. Chambers told us the old Air Force legend of the Gremlins. These are weird little creatures who fly about looking for unfortunate pilots who are either lost or in difficulties with the weather. Their chief haunts are ravines and the boulder-covered tops of hills. They fly about with scissors in each hand and try to cut the wires on an aeroplane.

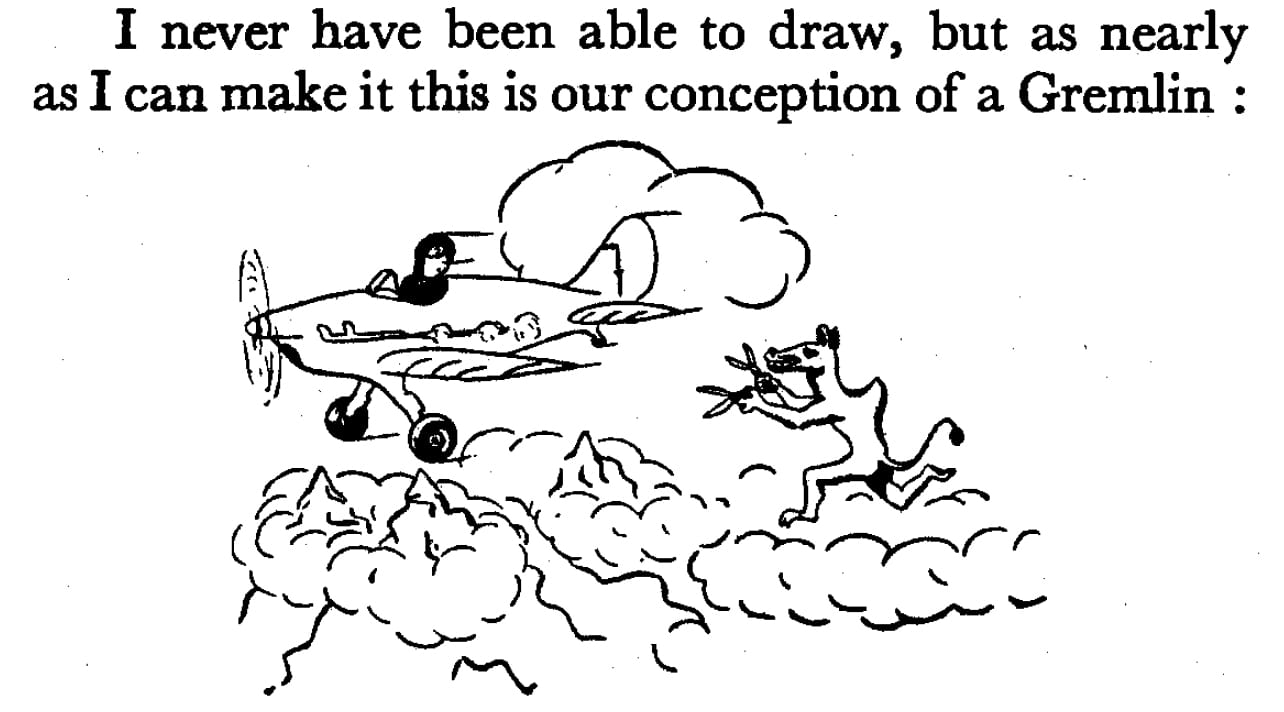

Gower also includes a drawing of a gremlin in her book:

And there is this from an article in the 28 March 1939 Daily Mail about RAF slang that purports to give the circumstances of the word’s coinage:

But the Gremlin is the latest imporiation [sic]. Have you met a Gremlin? The earth—or rather, the upper air—is full of them. Paunchy, horrific little men with leering faces and green eyes. They look over your shoulder. They start up from your fuselage. They sit on the joystick. They are the companions of gloom, despondency, and any form of trouble caused by “a job.” In other words, they are what you or I call the blues, the jitters, or spots before the eyes.

I won’t give him away, but a certain squadron leader, a gentleman occasionally of slightly intemperate habits, fathered the Gremlin. He took a machine up one day when, as a matter of strict pink-gin sense he should have stuck to his bicycle or his flat feet.

When the lorries, the ambulance, the fire brigade, and the mechanics picked him out of the bits and straightened the hole in the hedge, he merely sat up blandly, scratched his head and remarked fiercely that it never would have happened at all “if those damned Gremlins hadn’t been at me in the air.”

While we should not take this origin story as in any way authoritative, it is possible that the story details actual events—that is the crash occurred as described, only it wasn’t the first use of the word gremlin. If so, it may mark the transition between the senses. If the crash occurred as described, the pilot may have been blaming the gremlins of the ground crew (i.e., poor maintenance) for the crash, only later to be reinterpreted as due to the mythical creatures. Of course, that may be reading too much into it, and the whole thing may be fanciful.

And here is a use of gremlin from outside the world of aviation, in this case as a beneficial demon or fairy. It appears in a poem, titled Co-Editing, in the 11 February 1943 issue of the Massachusetts Collegian, the student newspaper of the Massachusetts State College. The 1943 date, in the midst of World War II, gives plenty of time for the military term to have insinuated itself into civilian speech:

Oh would there were a brain

Arattling round our head—

Passing courses is much more novel—

Than flunking them instead.

Or would there were a gremlin

Who, unsuspected and unseen,

Could add a point or twenty

To marks before they met the Dean

The fact that the origin is unknown is no bar to people making claims as to the origin of gremlin. None of these are supported by evidence. The most plausible is that the word is a variant of goblin, although how goblin could be transformed into gremlin cannot be explained. Other unsubstantiated explanations include that the word comes from the Fremlin Bros., a brewery in Kent whose ale was the cause of pilot error; that it comes from the Irish gruaimín, a gloomy or ill-humored person; that it is related to grimalkin, a word that usually refers to a crone or used as the name of a cat, but which appears in Shakespeare’s MacBeth as the name of a demon; or that it comes from either the Dutch gremmelen, meaning to stain or spoil, or griemelen, to swarm. Again, these are all speculation without evidence. We really need more examples of early use in order to determine how the term came about and how it made the transition from low-ranking officer to mythical creature. But such examples, if they were ever recorded, probably do not survive. But there is hope that as more archives are digitized, some will be found.

Sources:

I found a use of gremlin in a book in Archive.org allegedly from February 1918. All the other sources of this book give its first publication as 1947. As the scanned frontmatter clearly gives the 1918 date, it seems to be a misprint rather than a metadata error. The book is: Harding, M. Esther. Psychic Energy. Bollingen Series X Pantheon Books. New York: New York Lithographic Corporation, February 1918/47[?], 331. Archive.org.

Day, Wentworth. “There’s a Smile in the Air.” Daily Mail (London), 28 March 1939, 10/5. Gale Primary Sources.

“Flight-Lieutenant Hiawatha.” Aeroplane, 10 April 1929, 36.15, 576.

Gower, Pauline. Women with Wings. London: John Long, 1938, 200. PDF available (with permission) via the blog solentaviatrix.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, n.d., s.v. gremlin, n.1.

Liberman, Anatoly. “Gray Matter, Part 3, or, Going From Dogs to Cats and Ghosts.” OUPblog, 1 January 2014. https://blog.oup.com/2014/01/grimalkins-and-gremlins/

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2016, s.v. gremlin, n.

Sperry, Ruth. “Co-Editing.” Massachusetts Collegian, 11 February 1943, 2/4. Archive.org.

Image credits: Rod Serling (writer and creator), “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” The Twilight Zone, Paramount, 1963; fair use of a single, low-resolution frame to illustrate the topic under discussion. Pauline Gower, Women with Wings. London: John Long, 1938, 202; fair use of a drawing to illustrate the topic under discussion.