fleabag

Fleabag is a pejorative term for a bed or place of lodging or for a dirty, disreputable person. It is apparently a calque of the German Flohbeutel, a pejorative for a person lacking personal hygiene, although the English word may have been coined independently. An 1805 German-English dictionary has the following entry:

der Flohbeutel, des -s, plur. ut nom. sing. flea-bag, name given to a low person that is full of fleas.

Of course, this is evidence of the German usage, not the English.

We see the English fleabag a few years later, in the sense of a bed, in an account about Daniel McNeal, an American naval captain that appears in the London Chronicle dated 13 September 1811:

At another time, he gave liberty at Leghorn to two of his lieutenants, his surgeon, and purser, to go on shore, and immediately got under way with only one commissioned officer on board. His officers were not able to join him for four months, which they did at last at Malta, after having been cruising up and down the Mediterranean for four months in a Swedish frigate. When they came on board, he accosted them in the following handsome manner, “D—n your liv[e?]s, I thought you were in America before this—I have just done as well without you as if you had been on board, but as you are here I suppose I must take so much live lumber on board—you had better look out for your old flea-bags,” (meaning their cabins).

(It looks as if there was a printer’s error in “lives,” with an extra letter being erased.)

The London Chronicle defines fleabag as “cabin,” although it seems more likely, given the nature of sleeping accommodations on board naval vessels of the era, what was meant was “hammock.”

And there is this bit of dialogue in Charles J. Lever’s 1839 novel The Confessions of Harry Lorrequer uses fleabag more generally to mean a place of lodging, rather than just a bed:

Still I was not to be roused from my trance, and continued my courtship as warmly as ever.

“I suppose you’ll come home now,” said a gruff voice behind Mary Anne.

I turned and perceived Mark Anthony, with a grim look of very peculiar import.

“Oh! Mark dear, I’m engaged to dance another set with this gentleman.”

“Ye are, are ye?” replied Mark, eyeing me askance. “Troth and I think the gentleman would be better if he went off to his flea-bag himself.”

In my mystified intellect this west country synonym for a bed a little puzzled me.

The fact that the German Flohbeutel referred to a person and the English fleabag originally to a bed hints that the English word was independently created and not a calque. English use of the word to refer to a person does not appear until the middle of the twentieth century.

Further muddying the etymological trail is an Irish use of flea-park in a popular song, “De May-Bush,” allegedly from c. 1790. The song recounts a riot that happened in Smithfield, a suburb of Dublin, at around that date that was inspired by or in sympathy with the French Revolution:

Bill Durham, being up de nite afore,

Ri rigidi ri ri dum dee,

Was now in his flea-park, taking a snore,

When he heard de mob pass by his door.

Ri rigidi dum dee!

The problem is that there is no record of the song until it was published in 1843, well after fleabag was well established in English. And if the song does indeed date to c. 1790, there is no guarantee that this particular lyric is that old. Verses get added and dropped from popular songs all the time.

Sources:

“American Naval Biography” (13 September 1811). London Chronicle, 12–13 September 1811, 262–63 at 262. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Kuettner, Carl Gottlob and William Nicholson. New and Complete Dictionary of the German Language for Englishmen, vol. 1 of 3. Leipzig: E. B. Schwickert, 1805, 669. Google Books.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, n.d., s.v. fleabag, n., fleabag, adj.

Lever, Charles J. The Confessions of Harry Lorrequer. Dublin: William Curry, 1839, 266. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

“De May-Bush.” In “Ireland Sixty Years Ago.” Dublin University Magazine, 21.132, December 1843, 655–76 at 671. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2021, s.v. fleabag, n.

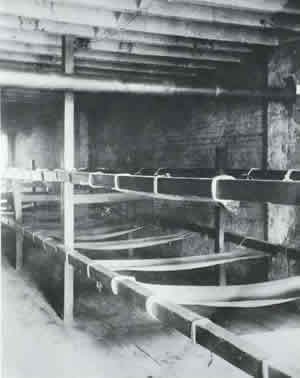

Photo credit: Jacob Riis, c. 1890. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.