fantastic

Fantastic comes via Old French from the Latin fantasticus or phantasticus, which in turn is from the Greek φανταστικός (phantastikos). The Greek verb φαντάζειν (phantazein) means to make visible and φαντάζεσθαι (phantazesthai) means to imagine, to have visions. Words like fantasy, phantom, and fancy come from the same root.

The adjective fantastic was brought to England by the Normans and has been recorded in English use since the late fourteenth century, when it could mean either “something false or supernatural” or “something produced by the mental faculty of imagination.” Fourteenth-century physicians believed the brain to be divided into three parts or cells. The fore-brain controlled imagination, the middle-brain judgment, and the rear-brain memory. In his Knight’s Tale, written c.1385, Chaucer alludes to this neurological understanding in a passage which is also one of the earliest recorded uses of fantastic in English:

And in his geere for al the world he ferde

Nat oonly lik the loveris maladye

Of Hereos, but rather lyk manye,

Engendred of humour malencolik

Biforen, his celle fantastik.

(And in his behavior for all the world he acted

Not only like the lover’s malady

Of heroes, but rather like mania,

Engendered of humor melancholic

In the fore-brain, his cell fantastic.)

By the end of the next century, fantastic had come to mean “imaginative, fanciful, or capricious,” and the older senses began fading away, although uses in these early senses can be found as late as the eighteenth century. And by the sixteenth century the word had also adopted the meaning of “extravagant or grotesque.”

But it wasn’t until the middle of the twentieth century that fantastic came to be used in the modern sense of “excellent, really good.” The transition is easy to understand, going from unbelievably good to simply good.

Both the Oxford English Dictionary and Green’s Dictionary of Slang have English crime novelist Margery Allingham use of fantastic in her 1938 novel The Fashion in Shrouds as their first citation for this “excellent” sense. But I believe this is in error, a misinterpretation caused by looking at snippet of text, with a significant portion elided, without context. Allingham uses the word five times in her novel. Four of those uses are clearly in the older sense of something that is beyond belief, something conjured by fantasy, and they are also used in negative contexts, to describe something horrible or unfortunate.

The fifth use of fantastic is the one included in the two dictionaries. Both give the citation as:

Oh, Val, isn’t it fantastic? […] It’s amazing, isn’t it?

The pairing with amazing makes it seem as if the word is being used in the positive sense, but what is omitted by the ellipsis and the lack of surrounding context is essential to understanding how Allingham is using the word. The immediate context of the quotation is a conversation about the sudden taking seriously ill by one of the characters in the novel, the speaker’s husband. The fuller passage reads:

“They’ve been preparing me for it [his death]. Oh, Val, isn’t it fantastic? I mean, it’s frightful, terrible, the most ghastly thing that could have happened! But—it’s amazing, isn’t it.”

On the next page there is this exchange:

Oh, Val, don’t look at me like that! I’m broken-hearted, really I am. I’m holding myself together with tremendous difficulty, darling. I am sorry. I am. I am sorry. When you’re married to a man, whatever you do, however you behave to one another, there is an affinity. There is. It’s a frightful shock. It’s a frightful shock.

This use of fantastic is clearly not in the sense of “excellent, really good.” We see that sense in a 1 January 1955 article in the Cincinnati Post about RCA-Victor reducing the price of its phonographs:

Roland Davis of Ohio Appliances, in charge of Victor Records distribution in this area is optimistic. “We had a fantastic Christmas sale. Dealers’ shelves ought to be pretty well cleaned out.

But while Davis clearly meant fantastic to mean good, the article makes clear that perspective was not shared by the record store owners, who faced a loss in revenue from the price cuts.

Fantastic has come a long way, from hallucinations and medieval neurology to simply being something really neat.

Sources:

Allingham, Margery. The Fashion in Shrouds (1938). London: Penguin, 1950, 118, 119. Archive.org.

Bell, Eleanor. “RCA-Victor Announces Price Cuts.” Cincinnati Post (Ohio), 1 January 1955, 5/1. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. “The Knight’s Tale” (c. 1385), The Canterbury Tales, lines 1:1372–76. Harvard’s Geoffrey Chaucer Website.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, n.d., s.v. fantastic, adj.

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. fantastik, adj.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. fantastic, adj. & n.

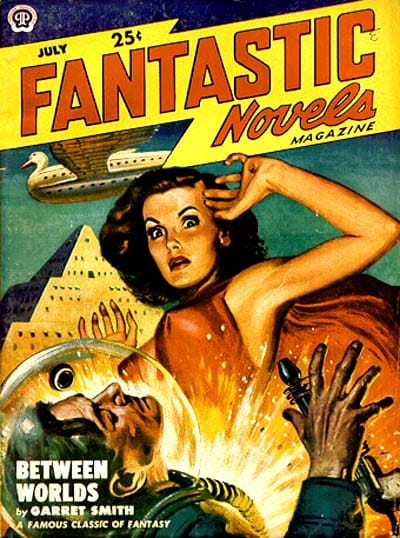

Image credit: Unknown artist, 1949. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.