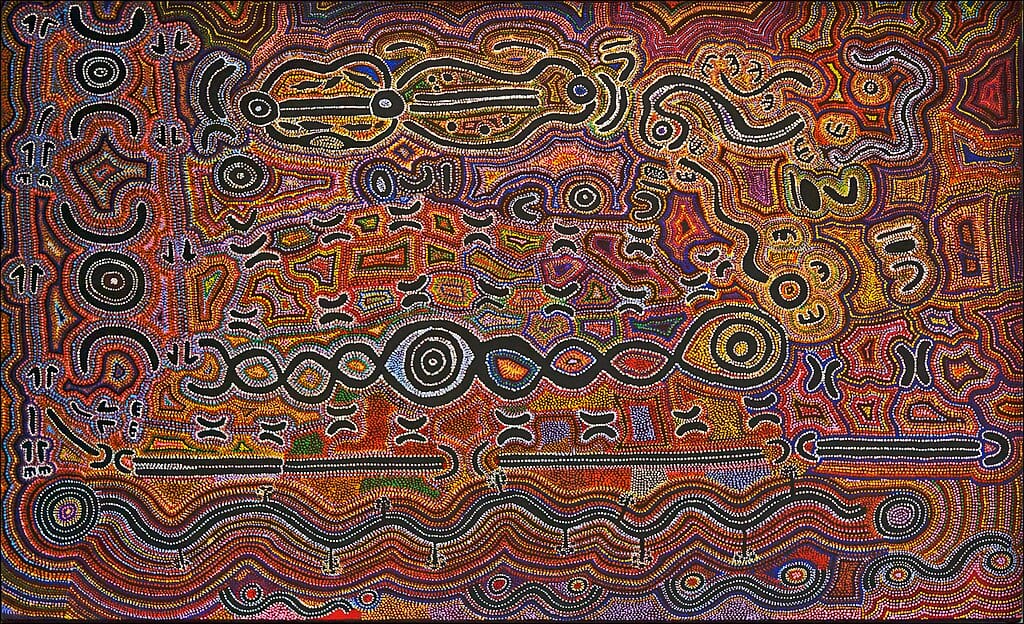

Dreamtime / Songline

Dreamtime and Songline are two words associated with Australian Aboriginal culture. But they are terms that have been misunderstood by Western popular culture, and the English calques are poor translations of the Aboriginal words. Tony Swain, who has studied Aboriginal religion extensively, writes:

Few topics have more allure than the Aboriginal conception of time; few have been discussed with less care. For those seeking primal wisdom, New Age englightenment or cosmic awareness, the subject has of course been irresistible. On the fringes of scholarship we encounter interpretations ranging from astounding superficiality to almost comical inventiveness.

Dreamtime is a calque of the Arrernte altjerreŋe, the Arrernte being an Aboriginal people of the Central Australia region of Northern Territory of Australia. It was originally glossed in 1896 by anthropologist Francis James Gillen as a sacred time before living memory that stretches back to creation:

The natives explain that their ancestors in the distant past (ulchurringa), which really means in the dream-times, for this is the manner in which the natives always speak of the long ago, acquired the art of “urpmalla” (fire-making) from a gigantic arrunga (Macropus robustus) called Algurawarina.

The accuracy of Gillen’s translation is now generally deprecated, with the meaning of the Arrernte word being something closer to eternal or uncreated, the location of spirits and things that could be visited via a dream or vision, and it does not in its Arrernte usage denote a time period. Swain contends that the Aboriginal concept that is poorly translated as dreamtime is better understood as “abiding events” that are inextricably linked to place or location. Here is an example of dreamtime being used by an Aborigine man, recorded in 2024 by Glenys Collard and Celeste Rodríguez Louro:

Our spirits are still in the dreamtime, even to these days now, they still woulda. Now we could be anywhere, and that family spirit, or good spirit is with us wherever we go, they’ll look after us, protect us from evil. And I’ll tell you one time, we was in Yarka Reserve there, back in the 60s, you know. […] Well then dad just, he was walking from the road into the reserve, and he seen us, but he seen all the family there, but there was another person there, like a spirit, standing there with us and he was wondering who that was. When he got up closer, closer, closer, it just vanished. It was one of the old people, just looking after them. And that’s what he told me, he was—before he passed away.

Still, the anglophone usage of dreamtime tends to correspond to Gillen’s definition. Here is an example from a 1959 academic thesis:

According to the myth, the Wollunqua existed in the sacred time called the Wingara by Warramunga people. This seems to be equivalent to what the Arunta Tribe knew as the Alcheringa and what is sometimes translated the “Eternal Dreamtime” by writers dealing with the Australian aboriginal cultures. It is the time of creation, the realm of the spirit-people, and the home of the ancestors. It is also the place of dreams and visions.

So dreamtime is a good example of a word that has acquired a very different sense in translation than it had in the original.

Closely associated with the dreamtime is the concept of the songline, a set of traditional songs that describe one’s relationship to the land. Like the dreamtime, songlines relate to creation myths, but they are not just origin stories set in the distant past, having a relevance to the present and future and one’s positionality in the landscape. Here is a definition and description from a 1989 academic thesis:

The songlines: A song is both a map and direction-finder. Providing you know the song you can always find your way across the country. In theory, the whole of Australia can be read as a musical score. The Ancestors sang the world into existence. All their words for “country" are the same as the words for “line.” Aboriginals imagine their territory as an interlocking network of lines or ‘ways through.’ To feel “at home” in that contry [sic] depends upon on [sic] being able to leave it. Everyone hoped to have at least four “ways out,” along which he could travel in a crisis. The songlines do not have frontiers, only roads and “handover points.”

By spending his whole life walking and singing his Ancestor’s Songline, a man eventually became the track, the Ancestor and the song.

Both Dreamtime and Songline are good examples of terms that when translated into another language acquire a somewhat different meaning than how they are understood in the original culture.

Sources:

Atwater, Kathryn Kellogg. The Great Wollunqua: A Study of Primitive Ritual (MA thesis). University of Chicago, 1959, 55. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Collard, Glenys and Celeste Rodriguez Louro. “From Spark to Flame: Decolonising Linguistics and the Creation of First Nations Medial Media.” In Finex Ndhlovu and Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, eds. Language and Decolonisation: An Interdisciplinary Approach. London: Routledge, 2024, 207–21 at 211. DOI: 10.4324/9781003313618-14.

Gillen, Francis James. “Notes on Some Manners and Customs of the Aborigines of the McDonnell Ranges Belonging to the Arunta Tribe.” In Baldwin Spencer, ed. Report on the Work of the Horn Scientific Expedition to Central Australia, vol. 4—Anthropology. London: Dulau, 1896, 161–96 at 185. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Hilb, Vera. Travelling: The Rotational Experience of Becoming-Nomad (MA thesis). University of Toronto, 1989, 71. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, September 2011, s.v. song line, n.; September 2012, s.v. alcheringa, n.; June 2014, s.v. dreamtime, n.

Image credit: Photo by dun_deagh, 2012. Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license. Original artwork by Bessie Nakamarra Sims & Paddy Japaljarri Sims (Warlpirri People), 1992.