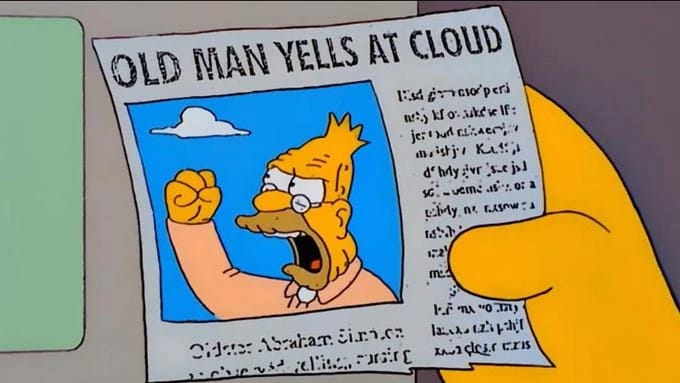

curmudgeon

A curmudgeon is an ill-tempered person, usually used in reference to an old man. The origin of curmudgeon is not known for certain, although etymologist Anatoly Liberman provides a reasonable explanation. What we do know for certain is that the earliest known use of the word can be found in Richard Stanyhurst’s history of Ireland, which appears in the 1577 edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles. (The OED cites the second, 1587, edition, but it also appears in the earlier one). The passage in question describes how, in 1537. Eleanor McCarthy accepted an offer of marriage to Manus O’Donnell, the curmudgeon in question, in order to guarantee the safety of her nephew, Conn O’Neill, but once his safety was guaranteed she did not go through with the marriage:

The Ladie Elenore hauing this, to hir contentation bestowed hir nephew, she expostulated verie sharpely with Odoneyle as touching hys villanie, protesting that the onely cause of hir match with him proceeded of an especiall care to haue hir nephew countenanced: and now that he was out of his lashe, that mynded to haue betrayed him, he should well vnderstande, that as the feare of his daunger mooued hir to annere to such a clownish Curmudgen, so the assuraunce of his safetie, should cause hir to sequester hirselfe from so butcherly a cuttbrote, that would be like a pelting mercenarie patche hyred, to sell or betray the innocent bloud of his nephew by affinitie, and hirs by consanguinitie. And in thys wise trussing vp bag and baggage, she forsooke Odoneyle, and returned to hir countrey.

Liberman suggests a Gaelic etymology, from muigean, “a churlish, disagreeable person,” plus car-, literally meaning “twist, bend” but when used as a prefix can have an intensifying effect, the Gaelic equivalent of the Latin dis-. Liberman’s etymology is not only linguistically plausible, but Stanyhurst was Irish and writing in an Irish context, so the Gaelic connection is a reasonable surmise.

Other suggested etymologies are more likely to be found but are not supported by evidence. One such is that it is a variation on cornmudgin. The Middle English muchen means to hoard. So a cornmudgin is someone who hoards grain. The problem with this explanation is the only known use of cornmudgin is from Philemon Holland’s 1600 translation of Livy’s Romane Historie, where the word appears twice. The first instance describes how, during a famine in 439 BCE, Spurius Melius, a wealthy grain merchant attempted to sell his grain at a low price in order to win the affection of the people and be crowned king:

Howbeit, the Claudij and Cassis, by reason of the Consulships and Decemvirships of their own, by reason of the honourable estate and reputation of their auncestors, & the worship and glory of their linage, tooke upon them, became hautie and proud, and aspired to that, wherunto Sp. Melius had no such meanes to induce him : who might have sit him downe, well enough, and rather wished and praied to God, than hoped once for so much, as a Tribuneship of the Commons. And supposed he, being but a rich corne-mudgin, that with a quart (or measure of come of two pounds) hee had bought the freedome of his fellow cittizens?

And the later appearance mentions fines for hoarding grain:

Also P. Claudius and Serv. Sulpitius Galbe, Ædiles Curule, hung up twelve brasen shields, made of the fines that certeine commudgins paid, for hourding up and keeping in their graine.

Since curmudgeon is older than this, it is more likely that Holland’s cornmudgin is a one-off pun, playing on curmudgeon, especially given Holland’s affinity for colloquial speech and how he “framed [his] pen, not to any affected phrase, but to a meane and popular stile.”

Another unsupported etymology is from Samuel Johnson’s 1755 dictionary:

CURMU´DGEON. n.s. [It is a vitious manner of pronouncing coeur mechant, Fr. an unknown correspondent.]

Coeur mechant means bitter or evil heart in French. Johnson’s dictionary is a landmark lexicographic achievement, but he got a lot wrong, and his etymologies are often particularly suspect. This one that Johnson received from the unknown correspondent is one such case. It’s not a bad off-the-cuff guess, but it’s not supported by any evidence.

Johnson’s etymology has also given rise to one of the worst lexicographic howlers in history when in 1775 lexicographer John Ash misread Johnson’s entry and gave the etymology as:

CURMUDG´EON (s. from the French cœur, unknown, and mechant, a correspondent).

Other suggestions made over the centuries are that it comes from a supposed Old English word *ceorlmodigan (churlish minded); from the medieval Latin corimedis (one who is liable to pay tax); or somehow related to dog/cur in the manger. None of these are supported by any evidence.

Sources:

Ash, John. The New and Complete Dictionary of the English Language, vol. 1 of 2. London: Edward and Charles Dilly and R. Baldwin, 1775, s.v curmudgeon. Archive.org.

Johnson, Samuel. A Dictionary of the English Language. 1755, 1773, s.v. curmudgeon. Edited by Beth Rapp Young, Jack Lynch, William Dorner, Amy Larner Giroux, Carmen Faye Mathes, and Abigail Moreshead. 2021. Johnson’s Dictionary Online.

Liberman, Anatoly, An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology, University of Minnesota Press, 2008, s. v. mooch, 162–65.

Livy. The Romane Historie. Philemon Holland, trans. London: Adam Islip, 1600, 4:150, 38:1004, and sig. A.vi–vii. ProQuest: Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s. v. curmudgeon, n.

Stanyhurst, Richard. “The Thirde Book of the Historie of Ireland, Comprising the Raigne of Henry the Eyght.” In The Historie of Ireland, Raphaell Holinshed, ed. London: John Hunne, 1577, 102. Archive.org.

Image credit: “The Old Man and the Key,” Lance Kramer, director; John Vitti, writer; Matt Groening, creator. The Simpsons, 13.13, broadcast 10 March 2002. Fair use of a single frame to illustrate the topic under discussion.