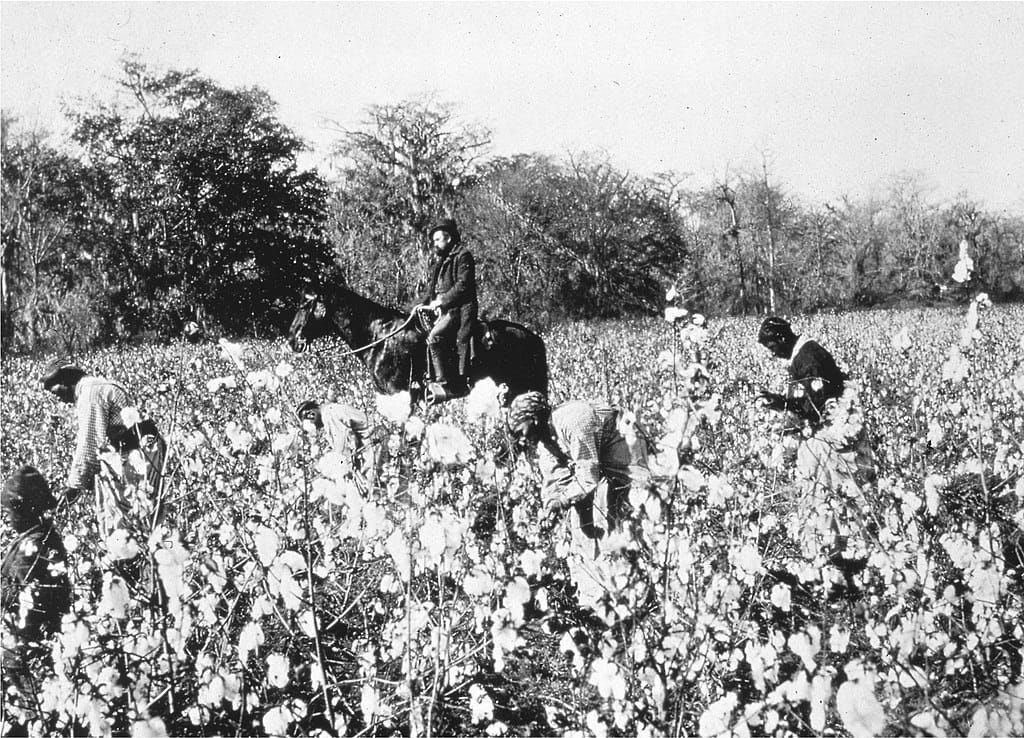

cotton-picking / cotton-picker

The adjective cotton-picking and the noun cotton-picker have as their origins a metaphor for slavery in the American South. While in today’s usage the racist intent has often been bleached away, the terms can still carry a racist connotation even if the speaker does not intend that sentiment.

The metaphor underlying the adjective is that of enslaved persons in the American South harvesting cotton. The Oxford English Dictionary records this literal sense of the noun cotton-picking as early as 1795 and cotton picker referring to machine that performs this task from 1833. Literal use of the terms in contexts clearly about harvesting cotton is rarely problematic. The problem comes in with the extended, figurative uses of the terms.

Figuratively, cotton-picking is used either as a general term of abuse for a person or as a euphemism for damned. One of the earliest uses, and it’s a transitional one that both literally refers to a enslaved person who picks cotton and is also used derogatorily, is from Solomon Northup’s 1853 autobiography Twelve Years a Slave, referring to a young black girl whose owner refuses to sell her along with her mother, thus separating them. He does this because the girl would be worth more in a few years:

“What is her price? Buy her?” was the responsive interrogatory of Theophilus Freeman. And instantly answering his own inquiry, he added, “I won’t sell her. She’s not for sale.[”]

The man remarked he was not in need of one so young—that would be of no profit to him, but since the mother was so fond of her, rather than see them separated, he would pay a reasonable price. But to this humane proposal Freeman was entirely deaf. He would not sell her then on any account whatever. There were heaps and piles of money to be made of her, he said, when she was a few years older. There were men enough in New Orleans who would give five thousand dollars for such an extra, handsome, fancy piece as Emily would be, rather than not get her. No, no, he would not sell her then. She was a beauty—a picture—a doll—one of the regular bloods—none of your thick-lipped, bullet-headed, cotton-picking n[——]rs—if she was might he be d—d.

Cotton-picking starts appearing regularly in print in the 1930s, often in non-racial contexts. Yet, these early extended uses are almost all from the American South, so the subtext is distinctly racist, even if the context is not. For instance there is this from Audie Murphy’s WWII memoir To Hell and Back, published in 1949. Murphy was a native of Texas:

Okay, gourd-head. Get that cotton-picking butt off the ground.

Here there is no overt racial context, it is one white soldier talking to another, but the underlying racist metaphor remains obvious.

The noun cotton-picker follows a similar pattern, although it has remained in use as a clear racial epithet. Extended use as a derogatory term for a Black person dates to at least 1880 in Elizabeth Avery Meriwether’s novel The Master of Red Leaf. The reference in that novel is to an enslaved woman who works as a nurse and thus is unlikely to be tasked with field work and is uttered by fellow enslaved women:

Her dress was less fashionable, was more rural, than the garments worn by the steamboat negresses. These latter quite looked down on Gilly, and one I heard call her a “Country Jake.”

“Yes, a regular cotton picker!” chimed in another.

“You may jes know,” said a third, “dis is de bery fust time in all her borned days she ever got outen sight o’ de cotton fiel’.”

Guy Williams’s 1930 Logger-Talk, a lexicon of lumberjacks in the Pacific Northwest defines cotton-picker as “a negro” in a list of ethnic epithets.

But in parallel with cotton-picking, the noun cotton-picker was also used, again starting in the American South, as a derogatory epithet for white people. But even though it is used for white people, the epithet is fundamentally racist, equating the person being insulted with blacks. From Jerome Harris’s 1919 Dizzed to a Million, a memoir about his WWI service in the field artillery:

What are these boys from the South? Are they cotton-pickers, corn-crackers, stump jumpers, ridge-runners or bog-leapers?

Some of the bleaching away of the racial connotations of these terms, so that present-day speakers use the term casually without racial intent, may stem from a 1953 Looney Tunes cartoon, Bully for Bugs, in which Bugs Bunny says:

Well, here I am. Hey, just a cotton-picking minute. This don't look like the Coachella Valley to me. [Looks at map] Hmm, I knew I should've taken that left turn at Albuquerque.

(The Historical Dictionary of American Slang gives a 1952 date for a Looney Tunes cartoon that uses “cotton-picking hooks,” referring to someone’s hands, but doesn’t identify the title. I’ve been unable to find it.)

Generations of kids have grown up watching this cartoon and hearing the term without realizing its racial connotations. Of course, these Looney Tunes cartoons, being products of their day, often contained racist content, with the more obvious bits edited out in later television broadcasts.

Sources:

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, accessed 27 July 2025, s.v. cotton-picking, adj., cotton-picker, n.

Lighter, J. E. Historical Dictionary of American Slang, vol. 1 of 2. New York: Random House, 1994, 491, 492, s.v. cottonpicker, n., cotton-picking, adj. & adv.

Maltese, Michael (writer) and Chuck Jones (director). Bully for Bugs (animated short film). Warner Brothers, 1953, timestamp 1:11. Dailymotion.com.

Meriwether, Elizabeth Avery. The Master of Red Leaf. New York: E. J. Hale and Son, 1880, 125. HathiTrust Digital Library.

Murphy, Audie. To Hell and Back. New York: Henry Holt, 1949, 41. Internet Archive.

Northup, Solomon. Twelve Years a Slave. Auburn: Derby and Miller, 1853, 85–86. HathiTrust Digital Library.

Oxford English Dictionary Online, 1972, s.v. cotton-picking, n. & adj.; 1893, cotton-picker, n.

Williams, Guy. Logger-Talk: Some Notes on the Jargon of the Pacific Northwest Woods. University of Washington Chapbooks 41. Seattle: University of Washington Book Store, 1930, 15. HathiTrust Digital Library.

Image credit: unknown photographer, 1850. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain photo.