chauvinism

Today we usually associate chauvinism with sexism, the belief that men are superior to women, but this is a relatively recent development in the word’s history. The original sense of the word was jingoism or superpatriotism, the blind, bellicose, and unswerving belief that one’s country is always in the right.

Chauvinism is an eponym, or a word formed from a person’s name, in this case Nicholas Chauvin. It is a near certainty that Chauvin never actually existed. He is a fictional character created to lampoon jingoistic patriots. The tales would have it that he was born in 1780 in Rochefort, France and served ably and well in Napoleon’s army, even being promoted to general, decorated, and granted a pension by the emperor himself.

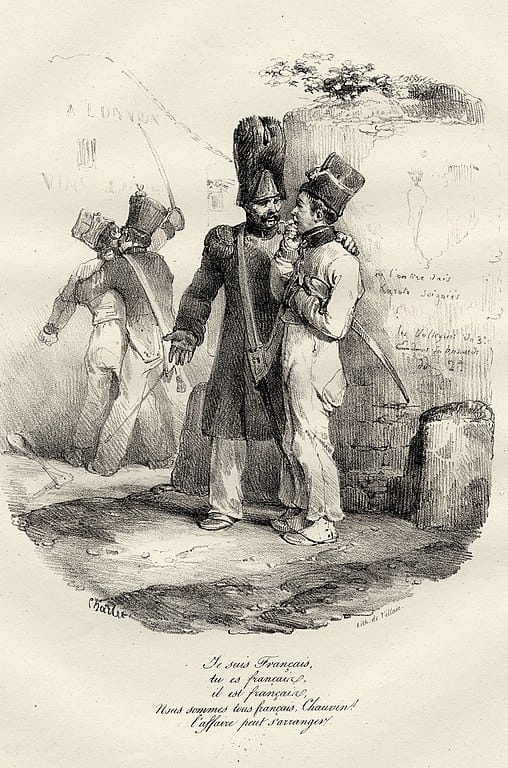

That was fiction. What is factual is that after the Napoleon’s exile to St. Helena in 1815 the name Chauvin began to be applied to those soldiers who idolized the former emperor and expressed a desire to return to the good old days of the empire. Most famously, the name was given to a ridiculous character in the Cogniard brothers’ 1831 play La Cocarde Tricolore (The Tricolor Cockade), who uttered the line, “je suis français, je suis Chauvin” (“I am French, I am Chauvin”).

Chauvinism and chauvinist soon crossed the channel and began to be used in English by the mid nineteenth century. The following appeared in the 17 May 1851 issue of Littell’s Living Age, a Boston periodical that reprinted items from other American and British newspapers and magazines:

Between the saying of Anteroches and that of Cambronne there is a great gap; we find that the revolution has passed through it. The gentleman, refined even to exaggeration, has disappeared, and we have instead the rude language of democracy—“La garde meurt et ne se rend pas”—this is heroism, no doubt, but heroism of another sort. Never did the chauvinism of this present time light upon a more cornelian device, but do you not see in it the theatrical affectation, the melo-dramatic emphasis of another race?

The quotation “la garde meurt et ne se rend pas” (the guard dies and does not surrender) is attributed to Pierre Cambronne, a general in Napoleon’s Imperial Guard who allegedly uttered the line when the British demanded his surrender at Waterloo. The line was almost certainly invented after the fact—especially given that Cambronne did indeed surrender and lived for another twenty-seven years. An alternative, and more plausible, version of what he said is simply, “Merde!”

But quickly the term began to be applied to superpatriots from other countries, not just France. The following item about Romania appeared in London’s The Examiner on 6 June 1868:

It is this nucleus of a party of parliamentary self-government which the Bratiano Government now endeavours to destroy by rousing a kind of Rouman “Chauvinism.” The cry at Bucharest, among the adherents of the Cabinet, is for the enlargement of the frontiers of the new State—even if it has to be done with Russian aid!

The association with sexism would not appear until the twentieth century. The phrase “Male Chauvinism” appears as a section header in an article in New York’s Daily Worker of 5 March 1932. And both male chauvinism and female chauvinism appear in the Christian Science Monitor of 7 August 1935:

William H. Adler, we find, is apparently wrong for the first time … Of our suggestion that a Woman’s Who’s Who smacks of female chauvinism, he says: “This means the reviewer considers the female cause a lost one … or does it?” No, it doesn’t … Both Webster and Oxford define chauvinism as jingoism, and mention no connotation of hopelessness … Perhaps the change of scene has affected Mr. Adler’s etymological sensibility … He has lately removed, temporarily, from Shanghai to London … We hope he goes back by way of Boston.

Another correspondent objected to this same comment … She inquired pointedly if in reviewing “America’s Young Men” we had suggested that it smacked of male chauvinism … She had us there—we hadn’t … Still, we believe our main point stands—that men and women should receive recognition without discrimination.

But male chauvinist may be a decade or more older, just unrecorded. There is this story from the New Yorker of 13 April 1940 that refers to an event that had allegedly occurred some fifteen years earlier in McSorley’s Ale House:

One night in the winter of 1924 a feminist from Greenwich Village put on trousers, a man’s topcoat, and a cap, stuck a cigar into her mouth, and entered McSorley’s. She bought an ale, drank it, removed her cap, and shook her long hair down on her shoulders. Then she called Bill a male chauvinist, yelled something about the equality of the sexes, and ran out.

While there is no particular reason to doubt that the incident happened, whether or not the phrase male chauvinist was uttered is in question.

While there are these older uses, male chauvinism came to the fore with second-wave feminism of the 1960s and 70s, often with the added epithet of pig. Here is the earliest example of male chauvinist pig that I have found. From an article about political protests in Canada that appeared in the Kitchener-Waterloo Record of 9 August 1969:

The placards represented various views. One read “Keep the state out of the nations bedrooms—allow abortions.” Another was “OUR PET is a male chauvinist pig.”

This association with sexism became so strong that often the male is simply dropped.

But chauvinism is not exclusively applied to sexists. It is also used in other contexts, but almost always with a modifier. In April 1955 an article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists decried the attitudes of those who professed a belief that their nation was superior to others in the field of science:

Even though scientists did not go as far as to confuse scientific knowledge with national ideological doctrine, they did, nonetheless, often make it a point of patriotic honor to practice a certain kind of scientific nationalism and almost indeed a scientific chauvinism.

And in his 1973 book The Cosmic Connection, astronomer Carl Sagan referred to oxygen chauvinism in our perceptions of what extraterrestrial life might look like

Oxygen chauvinism is common. If a planet has no oxygen, it is alleged to be uninhabitable. This view ignores the fact that life arose on Earth in the absence of oxygen. In fact, oxygen chauvinism, if accepted, logically demonstrates that life anywhere is impossible.

(The Oxford English Dictionary has a citation of Sagan using the phrase human chauvinism in this book, but I cannot find that phrase, or even the page number on which it allegedly appears, in any edition of the book I have access to.)

All in all, chauvinism is a pretty successful eponym, considering it’s named after someone who never lived.

Discuss this post

Sources:

Carney, Tom. “Pelted with Paper and Banana Peel.” Kitchener-Waterloo Record (Ontario), 9 August 1969, 2/2. ProQuest Newspapers.

Dubarle, Daniel. “Observations in the Relations between Science and the State.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 11.4, April 1955, 141–44 at 142/3. Google Books.

Hutchins, Grace. “11 Million Women Are a Big Factor in the Struggle of Toilers Against Bosses.” Daily Worker (New York), 5 March 1932, 4/7. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Mitchell, Joseph. “Profiles: The Old House at Home.” New Yorker, 13 April 1940, 23/3. New Yorker Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2000, s.v. male chauvinism, n.; second edition, 1989, s.v. chauvinism, n.

“The Political Examiner.” The Examiner (London), 6 June 1868, 1/2. Gale Primary Sources: British Library Newspapers.

Sagan Carl. The Cosmic Connection: An Extraterrestrial Perspective. New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1973, 44. Archive.org.

Sloper, L.A. “Bookman’s Holiday.” Christian Science Monitor (Boston, Massachusetts), 7 August 1935, Magazine Section 11/1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

“A Wreck of the Old French Aristocracy.” Littell’s Living Age (Boston, Massachusetts), 17 May 1851, 308–11 at 310. Gale Primary Sources: American Historical Periodicals from the American Antiquarian Society

Image credit: Nicolas Toussaint Charlet, c. 1825. British Museum. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.