cat's pajamas / whiskers / meow

The phrase the cat’s pajamas (also cat’s whiskers or cat’s meow), meaning something superlative or excellent, is indelibly associated with the 1920s and the jazz age. The phrase is often credited to cartoonist Thomas Aloysius “Tad” Dorgan, but while he did use the cat’s meow (and perhaps other variants), Dorgan was not the originator.

These three are only the most popular and long-lasting in a series of animal phrases constructed with the definite article the, such as the antelope’s tonsils, bullfrog’s beard, canary’s tusks, caterpillar’s camisole/kimono/spats, clam’s cuticle/garters, crocodile’s adenoids, duck’s quack, elephant’s tonsils, frog’s eyebrows, kipper’s knickers, kitten’s vest, lion’s bathrobe, oyster’s eyetooth, pig’s scream/whiskers, sandfly garters, snake’s eyebrows, and sparrow’s chirp. Not to mention other items belong to cats, such as cuffs, knee-knuckles, lingerie, nightgown, tonsillitis, and vest. And of course, there is the bee’s knees. It's easy to see how the idea of such rare or impossible things could give rise to a phrase denoting something that is exceptional or especially noteworthy.

The earliest use of the cat’s pajamas that I have found is in the unit newspaper of the US Army’s 21st General Hospital in Denver, Colorado of 17 July 1919. The phrase appears in an announcement that the army baseball team will play the team from the local Armour meat company:

“Say Medina,” said he, “this ball team of mine needs a lotta practice; so I’d like to have ’em come out here to the Coop every Thursday evening and stage a game with the soldiers boys. When we come out, we’ll bring something for the boys every time—some Armour food product you know. We’ll also bring along a couplea [sic] stoves on which we can cook the stuff and serve the hot wienies, fried ham sandwiches and such delectable food. Whad’ye say?”

Well, what else could O’Brien’s Helper say but that he thought it would be the cat’s pajamas to have feed like that dished up to the fellows every Thursday.

A year later in his syndicated column of 5 July 1920, Damon Runyan “records” this fictional conversation between two delegates to a political convention:

Second Delegate (angrily)—I tell you I ain’t been nowhere! I’m out here for business, and all I want now is to get somebody nominated, such as McAdoo, and go back to Springfield. I’m sick of this delay. It’s daffy people like you who are holding us back by runnin’ around town, and not being at the convention on time.

First Delegate (astounded)—Well, now, that’s sure the cats pajamas! Of course, I don’t get to the convention much, but everybody knows I’m for Jimmy Cox and they vote me that way whether I'm there or not.

This is passage is also notable in that it’s an early use of Springfield as a non-specific anytown, ala The Simpsons. (Contrary to popular belief, a town called Springfield does not exist in every state but only in thirty-four of them. Riverside, appearing in forty-six states, takes the prize.)

The cat’s pajamas also generated a short-lived dance of that name. From Kentucky’s Lexington Herald of 13 July 1921:

A couple of street dancers recently were arrested in Brooklyn for doing such vulgar steps as the “Frisco Dip” and “Elevated Swing.” Other interesting performances by the pair were the “Lame Dog” and the “Cat’s Pajamas.” Oh, Terpsichore, what outrages are committed in thy name!

And it was only a matter of time before the phrase appeared in that sub-genre of newspaper articles, those that pack an absurd amount of slang into a few column inches. Georgia’s Columbus Enquirer-Sun of 16 March 1922 has this fictional conversation:

Father—“Tell us all about the big city my lad.”

Only Son—“It’s the cat’s pajamas, dad, if you only have the boffos. What’s boffos? Why the berries, the jack, the kale. Of course, if you are a dad they give you the air. Get me mother!”

Mother—“I cannot say that I do my son.”

Unlike cat’s pajamas and the other animal phrases of its ilk, the cat’s meow and the cat’s whiskers have a different etiology, although they appear at about the same time. Cat’s whiskers and meows are common, and the sense of something exceptional arises out of the idea that these are things a cat is proud of.

The earliest such figurative use of the cat’s meow that I’m aware of is cited by the Oxford English Dictionary as coming from Pirate Piece of May 1921. Pirate Piece was the post-war unit newsletter of the 304th US Field Artillery Regiment, a “pirate piece” being a single gun detached from the unit to perform some mission or to go unnoticed by the enemy. I have been unable to find a copy, so I cannot verify the citation or provide it’s wider context:

A good letter, Quig, one like that every month would be the “cat's meow.”

The earliest use that I have verified is from a few months later, in an 11 September 1921 article in Baton Rouge, Louisiana’s State Times about movie stars and Hollywood power couple Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford:

Douglas looked like the cat’s meow, all dolled up in a nice gray flannel yachting suit and everything, and Mary, with a half-Nelson on his right forearm, in a blue silk suit lined with red silk and wearing shoes and stockings and a hat and white kid gloves and smiling like a May morning.

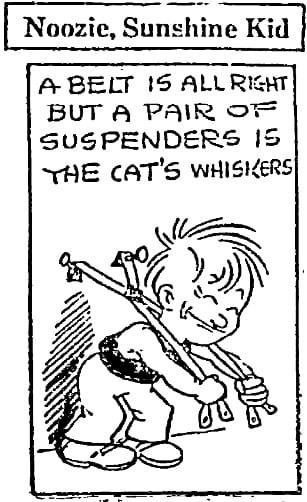

The cat’s whiskers makes its print debut, as far as I can tell, in a cartoon, Noozie, Sunshine Kid, appearing in Gulfport, Mississippi’s Daily Herald of 12 April 1922:

A belt is all right but a pair of suspenders is the cat’s whiskers

And three days later it appears in Omaha’s Sunday World-Herald of 15 April 1922 in an article about nine residents of the city:

Mr. Black was wearing a $10 derby at the time, and while in the midst of a sentence a gust of wind came along and blew it into the street. The brewer’s big horses coming down the road, stepped with great accuracy on the crown. Mr. Black cursed drink and all that goes with it and hen decided a $2 hat store would be the “cat’s whiskers” as it were. For sixteen years he covered the blocks of Omaha’s best citizens selling hats first from Sixteenth street near Dodge and then from the old Pease store near Fifteenth and Farnum.

There may, of course, be earlier instances of any of these yet to be found, especially of the cat’s meow or the cat’s whiskers, as literal uses of these phrases abound and it’s difficult to sift the wheat from the chaff.

Sources:

Carroll, Ramond G. “Women Who Refuse to Bear the Names of the Men They Marry.” Columbus Enquirer-Sun (Georgia), 16 March 1922, 7/4. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Doug and Mary in Living Picture, ‘Guests of Boy Scouts,’ Make Hit” (11 September 1921). State Times (Baton Rouge, Louisiana), 27 September 1921, 7/3. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Estes. “Sports Chat.” Lexington Herald (Kentucky), 13 July 1921, 6/4. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, n.d., s.v. cat’s pyjamas, n., cat’s meow, n., cat’s whiskers, n.

Griswold, Gerard Coburn. “What Nine Omahans Were Doing at 25.” Sunday World-Herald (Omaha, Nebraska), 15 April 1922, Magazine 3 and 11 at 11/2–3. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Noozie, Sunshine Kind (cartoon). Daily Herald (Gulfport, Mississippi), 12 April 1922, 1/1. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. cat, n.1.

Runyan, Damon. “Two Delegates Talk.” Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee), 5 July 1920, 4/5. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Wieners, Fried Bacon, Salisbury Steaks for Loyal Rooters.” ’Tenshun, 21! (US Army General Hospital 21, Denver, Colorado), 17 July 1919, 1/6. ProQuest Magazines.

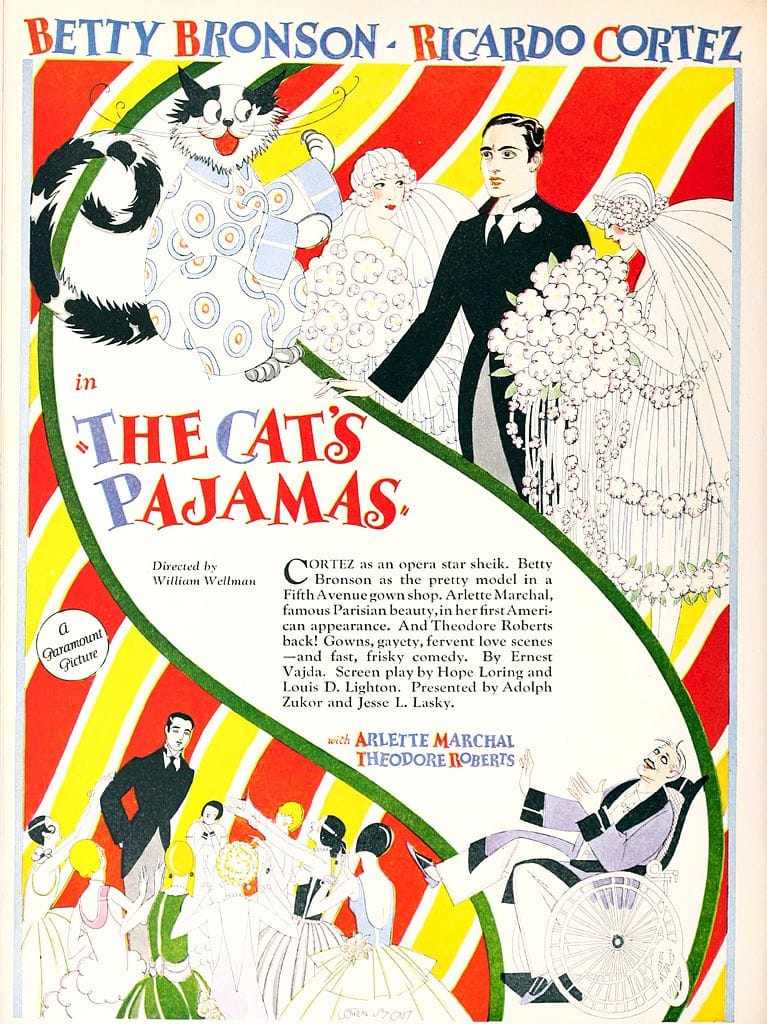

Image credits: The Cat’s Pajamas (advertisement), Paramount Pictures, 1926. Public domain image; Noozie, Sunshine Kid, unknown artist, 1922. Public domain image.