bible

Bible has several meanings in Present-Day English usage. Most commonly it refers to the Christian and Jewish scriptures, and when used this way it is generally capitalized. But bible can also be used in an extended sense to mean any authoritative book or collection of writings, in which case it is usually written in lower case. In the past, bible could also refer to any large book or tome.

The English word is borrowed from both the Old French bible and the medieval Latin biblia—the French word, of course, also comes from the Latin. The Latin biblia is a late addition to that language. For instance, it does not appear in Anglo-Latin sources until the close of the eleventh century. Jerome referred to his translation of the Christian scriptures as a bibliotheca, that is a library or collection of books. The Latin, in turn, is borrowed from the Greek βιβλία (biblia, books). The Greek word is the plural of βιβλίον (biblion), a diminutive of βίβλος (biblos), literally meaning the inner bark of papyrus and by extension a paper or scroll or, in later use, a codex or book.

One of the earliest uses of Bible is in the poem Cursor Mundi, written in the thirteenth century in a Northumbrian dialect, but with manuscripts dating to the late fourteenth. The passage in question recounts the tale of Noah and the flood:

Quen noe sagh and was parseueid

Þat þis rauen him had deceueid,

Lete vte a doue þat tok her flight

And fand na sted quare-on to light;

Sco com a gain wit-outen blin,

And noe ras and tok hur in;

Siþen abade he seuen dais,

Efter þat, þe bibul sais,

Þan he sent þe dofe eftsith;

Sco went forth and cam ful suith,

Son sco cam and duelld noght,

An oliue branche in moth sco broght.

(When Noah saw and had perceived

That the raven had him deceived,

[He] let out a dove that took to flight

And found no place whereon to light.

She returned without tarryin’;

Noah rose and took her in;

Then he abided for seven days,

After that, the Bible says,

Then he sent the dove again;

She went forth and returned very swiftly;

Soon she returned, delaying nought;

An olive branch in her mouth she brought.)

(Another manuscript, Oxford, Bodleian Library, Fairfax MS 14 written in a West Midland dialect and copied at roughly the same time, spells the word bible.)

By the late fifteenth century, bible had acquired other senses. It could refer to a large tome or book. This sense can be found in the poem Piers Plowman. In this passage, the character Anima is speaking to corrupt clergy:

For as it semeth ye forsaketh no mannes almesse—

Of usurers, of hoores, of avarouse chapmen—

And louten to thise lords that mowen lene yow nobles

Ayein youre rule and religion. I take record at Jesus,

That seide to hise disciples, “Ne sitis acceptors personarum.”

Of this matere I myghte make a muche bible.

(For as it seems you forsake no man’s alms—

Of usurers, of whores, of avaricious merchants—

And bow to these lords that might lend you coins

Contrary to your rule and religion. I witness what Jesus

Said to his disciples, “Do not be greedy people.”

About this matter I could write a long book.)

The Present-Day sense of an authoritative book dates to the early eighteenth century, if not earlier. Here is a use from the issue of the newspaper The Craftsman, dated 16 November 1728:

As a farther Proof of your Sincerity in the Love of your Country, be careful and diligent in the Use of all those Means, which your glorious Ancestors have afforded you for the right Understanding and Preservation of our happy Constitution; “particularly by reading Magna Charta, (the Englishman’s political Bible) and making it familiar to you.

Sources:

Cursor Mundi, Part 1 of 6. Richard Morris, ed. Early English Text Society O.S. 57. London: Oxford UP, London, 1961, 116, lines British Library, Cotton MS Vespasian A.iii. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

D'Anvers, Caleb. The Craftsman, No. 124, 16 November 1728. In The Craftsman, vol. 3. London: R. Francklin, 1731, 298. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources. R.E. Latham and D.R. Howlett, eds. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2018, s.v. biblia, n. Brepols: Database of Latin Dictionaries.

Langland, William. The Vision of Piers Plowman (B text), second edition. A.V.C. Schmidt, ed. London: J.M. Dent (Everyman), 1995, Passus 15, lines 84–89.

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. bible, n.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. Bible, n.

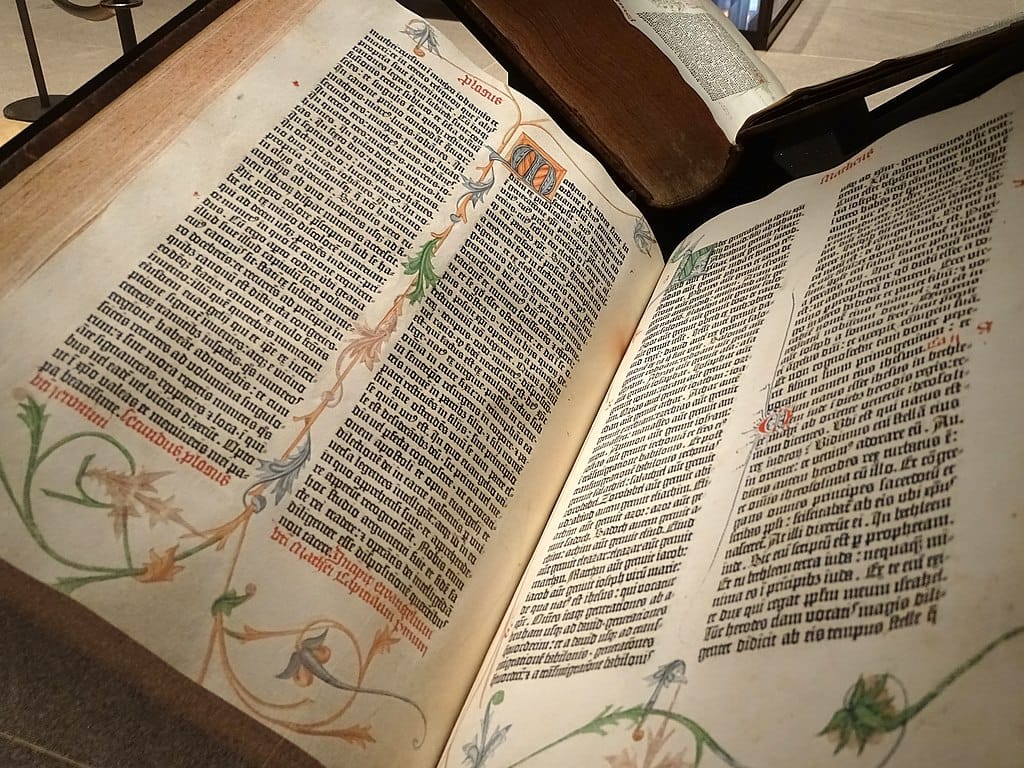

Photo credit: Adam Jones, 2018, Flickr.com. Wikimedia Commons. Used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.