bee's knees

Most people associate the bee’s knees, meaning something that is excellent or otherwise superlative, with the Roaring ’20s and the Jazz Age. But while the phrase did come into its present-day meaning shortly before and experienced a rise in popularity during that era, it has precursor meanings that predate it by a considerable number of years. And while it is popularly considered to be an Americanism, early uses can be found in Australia, Ireland, and Britain, making the region of origin difficult to pin down. The phrase is often attributed to cartoonist Thomas Aloysius “Tad” Dorgan, but while he may have used the phrase, he did not coin it.

The phrase is first attested to the late eighteenth century in the sense of something very small. Then, at the turn of the twentieth century, it came to refer to some nonsense thing, and a decade or so later the present-day sense of something excellent appeared. There is some evidence that this sense of bee’s knees was popular among American doughboys during the First World War, and that sense ballooned among the general public in the post-war years, as the soldiers returned from service.

The bee’s knees is only the one of the more popular and long-lasting in a series of animal phrases constructed with the definite article the, such as cat's pajamas. Other include the antelope’s tonsils, bullfrog’s beard, canary’s tusks, caterpillar’s camisole / kimono / spats, cat’s cuffs / kneeknuckles / lingerie / nightgown / tonsilitis / vest, clam’s cuticle / garters, crocodile’s adenoids, duck’s quack, elephant’s tonsils, frog’s eyebrows, kipper’s knickers, kitten’s vest, lion’s bathrobe, oyster’s eyetooth, pig’s scream / whiskers, sandfly garters, snake’s eyebrows, and sparrow’s chirp. It's easy to see how the idea of such rare or impossible things could give rise to a phrase denoting something that is exceptional or especially noteworthy.

The earliest use of bee’s knees, actually a reference to it being used, that I’m aware of is in an 1896 issue of the British journal Notes and Queries. The writer is citing a letter written to his grandmother, dated 27 June 1797:

A ”Bee’s Knee” (8th S. x. 92, 199).—I find the phrase “As big as a bee’s knee” in a letter from Mrs. Townley Ward to her sister, my grandmother, dated 27 June, 1797: “It cannot be as big as a bee’s knee.”

Notes and Queries is a long-running (since 1849) scholarly journal that publishes informal notes and questions about language, literature, and history to which other readers respond. It is, essentially, the print precursor of an internet message board or social media site. It’s still being published, although the internet has short-circuited its utility as a research tool.

This use of bee’s knee (it is usually in the singular in this sense) as a comparison to something very small would continue through to the twentieth century. I have an American usage from Philadelphia’s Atkinson’s Saturday Evening Post of 12 November 1831:

Waiter; walk a kidney three times before the fire, and bring it me with a shallot as hot as the first broadside; and, d’ye hear, put a bite of butter not bigger than a bee’s knee on the bilge of it; mind that!

And there is this from The Great Metropolis, published in New York City in 1837, but the account is about London, and this is probably an American reprint of an originally British book:

“Ned, my jolly old fellow,” said one cartman to another, as they both sat quaffing a pot of porter in the tap-room—“Ned, von’t [sic] you have a slice of this here loaf?

“I’m not a bit hungry,” said Ned.

“Take a slice; there’s a good fellow.”

“Well, if I do,” said Ned, “let it be only the bigness of a bee’s knee.”

But at the turn of twentieth century the plural bee’s knees began to be used to refer to some fantastic or fanciful object, often a jocular stand-in for some exotic and foreign foodstuff. This new sense would seem to be a generalization of something absurdly small to something just absurd, often some exotic foodstuff. The earliest use of this sense that I’m aware of is from the Daily Globe of Fall River, Massachusetts of 5 September 1901:

A large plate glass window in Holden & Hindle’s store was broken about 11.15 o’clock last night. George Borden, of Westport, vender of watercress, bee’s knees, clam’s ankles, etc., did the trick, but he claims it was purely accidental.

And the next year there is this in the 27 October 1902 issue of the Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle:

In another of the dozen or so artictles [sic] about the Eagle in Saturday morning’s paper, Mr. Hinkley states that he will pave between the tracks IF Mr. Butts is elected. If we thought for a single minute that this would be done, hand if we wouldn’t vote for Allison. Such a proposition is about as safe as the man who went into a restaurant and offered $100 for some fried bee’s knees.

And writer Zane Grey used the phrase in his 1909 short story The Short Stop. Grey was chiefly known for his novels about the American West, but he had played baseball for the University of Pennsylvania and for several years in the minor leagues, and this story is about the sport, although the passage in question has nothing to do with baseball:

“Wall, how's things? Ploughin’ all done? You don’t say. An’ corn all planted? Do tell! An’ the ham-trees growing all right?

“Whet?” questioned the farmer, plainly mystified, leaning forward.

“How’s yer ham-trees?”

“Never heard of sich.”

“Wall, don-gone me! Why over in Indianer our ham-trees is sproutin’ powerful. An’ how about bee’s knees? Got any bee’s knees this spring?”

On the other end of the literary spectrum we find this in the 1 September 1910 issue of the Mirror, the newspaper of the prison in Stillwater, Minnesota:

Oliver Twist of the Steward’s department informed us that he will tender a banquet to The Mirror Sporting Writers’ Association and forwards a copy of the menu which we publish below:

Mock Duck Soup.

Young Onion Tops (decapitated)

Spinach a la Si Haskell

Seedless Orange Seeds Stewed

Broiled Bees’ Knees

Fried Ice Cream

New Potato Peelings a la Olive

Rimless Doughnuts

Distilled Water

And there is this that appeared in Nevada’s Tonopah Daily Bonanza of 14 August 1912. The article is an opinion piece supporting Clarance Darrow’s defense of the McNamara brothers, labor unionists who detonated a bomb at the Los Angeles Times newspaper in 1910, killing twenty-one people. Darrow managed to get them a plea deal that spared them from the death penalty:

I do not favor violence. I have fought labor unions all my life. I drew up the famous anti-picketing ordinance, yet I had walked the streets all day trying to sell my labor to feed my hungry and crying babies, and couldn’t get work, while others were living on bees’ knees, humming bird’s tongues and giving monkey dinners. I would commit violence. I would tear the front off the first national bank with my finger nails.

A few years earlier, starting in 1905, we get a series of Australian uses of the phrase. The first, and most interesting, is in a 3 March 1905 letter by folk-singer Harold Percival “Duke” Tritton. The letter, which is filled with slang, was found among his papers following his death in 1965 and mined by lexicographers for the verbal treasures it contains:

And I am popular with the family, and the neighbours. So everything is Jakalorum. I’m teaching Mary and all the tin lids in the district to dark an’ dim, and they reckon I’m the bees knees, ants pants and nits tits all rolled into one.

Tritton seems to be using bee’s knees in the superlative sense, which would make it, by several years, the earliest such use. But it also refers to the earlier sense of size with its association with ants pants and nits tits. That would make it something of a transitional use between the two senses, but its appearance in Australia is puzzling. Did the later sense develop there first? Or was the superlative sense in use on several continents before it started appearing in print?

A few months later we get another Australian sense, but this one seems to be a nonce use, a confusion with another term. The music column of Adelaide’s Evening Journal of 19 August 1905 has this:

However, among the characteristic features of a Stradivarius violin are the bees knees of the pfurling [sic], which are kept closer to the inner corners than in most instruments, and hence display a greater margin of wood on the outer edges of the corners.

Purfling are the thin, inlaid strips of wood running on the edges and backs of stringed instruments. The purfling is not merely decorative, but also protects the wood from cracks as it ages and may have an effect on the tone of the instrument. The pointed edges of the instruments where the two ends of the purfling connect, usually known as the mitre, is also commonly called the bee sting. The use of bees knees in this article would appear to be an error for bee sting. I know of no other uses of bees knees in this musical sense.

After that false alarm, we get another anomalous use in Perth’s Truth of 20 January 1906. A reader replies to another reader’s request for information with this:

“Inquirer” (Kalgoorlie): 1. Yes; bee’s knees are the latest. 2. Mr. G. Thyne, of Messrs. D. and W. Murray, Kalgoorlie, should be able to advise you on the subject.

This newspaper column is analogous to Notes and Queries, with readers asking questions and getting responses from others. Unfortunately, I cannot locate the original question from the Inquirer in Kalgoorlie, so what is meant by bee’s knees here is, for the moment at least, unknown.

Another anomalous use is in a series of classified ads in Victoria’s Bendigo Advertiser starting on 27 September 1910 that ran for several months. The ad is for a clothing store, but what exactly is meant by the phrase isn’t clear from the available context:

BEES Knees to You I’m off to Wilkins and Jones’s for my Summer Suit Busy B. Charing X.

Duke Tritton’s 1905 use of the phrase might be the earliest in the superlative sense, but the first unambiguous use in that sense actually comes from England. It appears in a short piece about a local bakery in the Woolwich Gazette and Plumstead News of 5 July 1910:

Genuine Scotch shortbread is difficult to obtain in this district. Lots of substitutes are passed off on the too readily believing public, but poor stuff they are at the best. However, there is one place, at any rate, where this delicious edible can be had in its proper crispness and flavour. Mr. George Paterson’s 13, Eton Road, Plumstead. The real “bee’s knee” it is. Besides shortbread Mr. Paterson—who, by the by, was manager of the Royal Arsenal Co-operative bakery for we don’t know how many years—makes specialities of wedding, birthday, and christening cakes, breakfast scones and rolls, and Scotch hot pies.

Since it’s a reference to food, it may be a transitional use from the sense of an exotic foodstuff, although how exotic Scottish shortbread would be to 1910 Londoners is open to question. But in any case, this use in a local London paper, along with Tritton’s use five years earlier in Australia, throws a monkey wrench into the idea of the phrase being an Americanism.

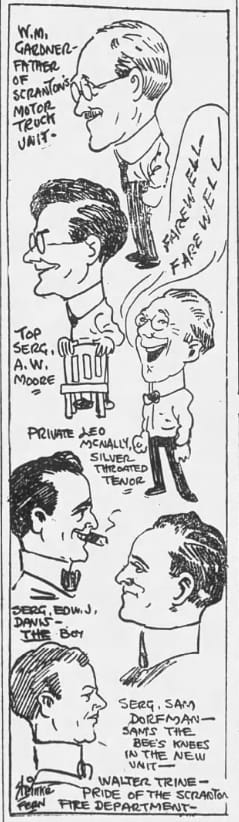

The first American use of bee’s knees in the superlative sense that I’ve found is in a cartoon in Pennsylvania’s Scranton Republican of 15 August 1917. The cartoon depicts several members of a newly formed US Army unit from Scranton and describes one man as the “bee’s knees of the new unit.” It is also the first one associated with World War I.

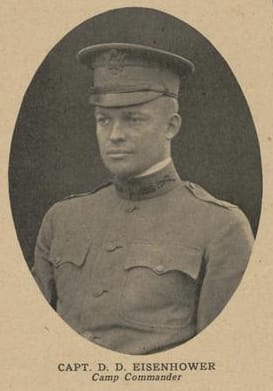

Another First World War usage is found in the January 1918 issue of Treat ’Em Rough, the unit magazine of the US Army Tank Corps training facility in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. A unit that, incidentally, was commanded by Captain Dwight D. Eisenhower:

Lieut. McNamara is the bee’s knees when it comes to drilling. 1-2-3-4, hep, hep, tell the sergeant to get in step. What he don’t know about drilling isn’t worth knowing.

The use of the phrase would explode over the coming decade as the soldiers came home from the war. Damon Runyan penned this fictional conversation between two delegates to a political convention in his 5 July 1920 syndicated column:

Second Delegate—"There’s plenty doing in Springfield for me. I’m sick and tired of staying around here. You must be nutty to want to stay.”

First Delegate—"Well, now, ain’t that the bee’s knees! Of course, I don’t get to the convention much, but everybody knows I’m for Jimmy Cox and they vote me that way whether I'm there or not. Why I’m having a swell time here.”

Runyan wasn’t the first to use phrase, nor was he the only major writer of the era to use the new superlative sense of bee’s knees, but his column was printed in papers across the United States and marked the sense’s entry into print discourse and eventually an indelible association with the Jazz Age.

Sources:

“304 Battalion. Co. B.” 37/1. Treat ’Em Rough (US Army Tank Corps, Camp Colt, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania), January 1918, 37/1. ProQuest Magazines.

“Among the Politicians.” Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle (New York), 27 October 1902, 5/4. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

“Bobbles.” Mirror (Stillwater, Minnesota), 1 September 1910, 4/3. Newspaper Archive.com.

“Chapter VII: Metropolitan Society—The Lower Class.” The Great Metropolis. New York: Theodore Foster, 1837 161. In Foster’s Cabinet Miscellany, vol. 5. Gale Primary Sources: American Historical Periodicals from the American Antiquarian Society. (The dates are a bit confused here. The book has a title page with the 1837 date, but volume of Foster’s Cabinet Miscellany in which it is enclosed bears a date of 1836.)

Classified advertisement. Bendigo Advertiser (Victoria), 27 September 1910, 6/3. NewspaperArchive.com.

“Declares Darrow Did Remarkable Thing in Saving Lives of the M’Namara Brothers.” Tonopah Daily Bonanza (Nevada), 14 August 1912, 1/2. NewspaperArchive.com.

“East End Echoes.” Daily Globe (Fall River, Massachusetts), 5 September 1901, 7/1. Newspapers.com.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, n.d., s.v. bee’s knees, n.

Grey, Zane. “The Short Stop.” Pittsburg Press (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), 11 October 1909, 6/6. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

“Motor Truck Unit Enjoys Jolly Time.” Scranton Republican (Pennsylvania), 15 August 1917, 4/6. Newspapers.com.

“Musical Notes.” Evening Journal (Adelaide, South Australia), 19 August 1905, 6/4. NewspaperArchive.com.

“Our Letter-box. Answers to Correspondents.” Truth (Perth, Western Australia), 20 January 1906, 3/4. NewspaperArchive.com.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. bee, n.1.

“Replies.” Notes and Queries, 8.248. 26 September 1896, 260. Gale Primary Sources: American Historical Periodicals from the American Antiquarian Society.

Runyan, Damon. “Two Delegates Talk” (4 July 1920). Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee), 5 July 1920, 4/5. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Seen and Heard.” Prahran Telegraph (Melbourne, Victoria), 24 April 1909, 5/1. NewspaperArchive.com.

“Tol Lol Penny.” Atkinson’s Saturday Evening Post (Philadelphia), 12 November 1831, 4/2. ProQuest Magazines.

“Trade Touches.” Woolwich Gazette and Plumstead News (England), 5 July 1910, 4/7. British Newspaper Archive.

Tritton, Harold Percival “Duke.” Letter, 3 March 1905. In John Meredith, Dinkum Aussie Slang: A Handbook of Australian Rhyming Slang (1984), Kenthurst, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press, 1993, 12–15 at 15. Archive.org. https://archive.org/details/dinkumaussieslan0000mere/page/15/mode/1up

Image credits: Honey bee: Charles J. Sharp, 2014. Wikimedia Commons. Used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Violin: Rocket12793, 2019, Wikimedia Commons, used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Scranton Republican (Pennsylvania), 15 August 1917. Public domain image.

Eisenhower: Treat ’Em Rough, 1 January 1918, 3. Public domain image.