bachelor

This word for an unmarried man has had several meanings over the centuries. Bachelor is borrowed from Anglo-Norman bacheler, which is presumably from the Latin baccalaria, a division of land. The normal sound changes would lead us to conclude that the French is from the form baccalaris, but that form is rare and not attested to until the medieval period, and those instances may be borrowings from one or more of the Romance languages that had by then split from their Latin ancestor. The adjectives baccalarius and baccalaria appear in the eighth century, applied to male and female farm workers, so bachelor may have originally referred to a man who worked on a farm.

By the turn of the fourteenth century we see bachelor appear in English, and here it had the meaning of a squire or young knight. We see it in the life of St. John the Evangelist in the Early South English Legendary. The story is of St. John turning ordinary items into precious metals and gems for two dissolute and penniless young knights:

Seint Iohan tornede þis ȝeordene sone : in-to puyr gold and cler, And þe stones to ȝimmes preciouse : þoruȝh ore louerdes pouwer, And þis twei wilde Bachilers : he ȝaf it euer-ech del.

(Saint John soon turned these arrows into pure and bright gold and the stones to precious gems through our Lord’s power, and these two impetuous bachelors he gave each one a portion.)

By the end of the that century the word added two new senses, that of a university graduate and the one most familiar to us today, that of an unmarried man. Both of these senses appear in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. The first, that of a university graduate is in The Franklin’s Tale:

He hym remembred that, upon a day,

At Orliens in studie a book he say

Of magyk natureel, which his felawe,

That was that tyme a bacheler of lawe,

Al were he ther to lerne another craft,

Hadde prively upon his desk ylaft;

(He remembered that one day in Orleans, in a study, he had seen a book of natural magic, which his fellow who has at that time a bachelor of law, although he was there to learn another craft, had covertly left upon his desk.)

And the second, that of an unmarried man, is found in the Merchant’s Tale:

And trewely it sit wel to be so,

hat bacheleris have often peyne and wo;

On brotel ground they buylde, and brotelnesse

They fynde whan they wene sikernesse.

They lyve but as a bryd or as a beest,

In libertee and under noon arreest,

Ther as a wedded man in his estaat

Lyveth a lyf blisful and ordinaat

Under this yok of mariage ybounde.

(And truly it is well to be so that bachelors often have pain and woe. They build on brittle ground, and they find mutability when they expect security. They live as but a bird or as a beast, in liberty and under no restraint, whereas a wedded man in his estate lives a blissful and orderly life bound under this yoke of marriage.)

These two senses are the most common today.

But there are other senses of the word. In Canada and South Africa, a bachelor apartment is a single room with attached bathroom, what in the United States is termed a studio apartment. From a classified advertisement in Toronto’s Globe and Mail from 27 November 1945:

BACHELOR

Apartment wanted by demobilized naval officer returned from five years overseas. Bank references. Apply Box 341, Globe and Mail.

By 1963 the phrase bachelor apartment was being clipped to simply bachelor.

Sources:

Anglo-Norman Dictionary, 2007, s.v. bacheler, n.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. “The Franklin’s Tale.” The Canterbury Tales, lines 5.1123–28. Harvard’s Geoffrey Chaucer Website.

———. “The Merchant’s Tale.” The Canterbury Tales, lines 1277–85. Harvard’s Geoffrey Chaucer Website.

Classified advertisement. Globe and Mail (Toronto), 27 November 1945, 25/1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles (DCHP-2), second edition, 2017, s.v. bachelor apartment, n.

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. bacheler, n.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. bachelor, n.

“Saint John the Evangelist.” The Early South English Legendary. Carl Horstmann, ed. London: N. Trübner, 1887, 410, lines 263–65. Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Laud 108, fol. 171v.

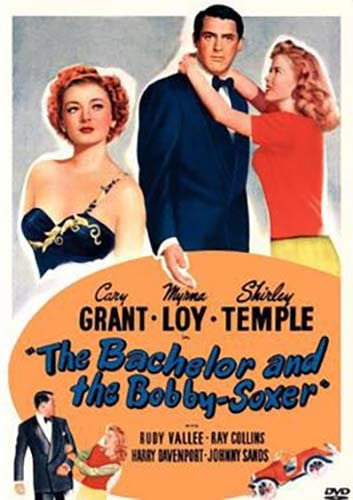

Image credit: 1947, RKO Radio Pictures. Wikipedia. Fair use of a low-resolution copy of a copyrighted work to illustrate the topic under discuassion.