America

The continents of North and South America are named for Amerigo Vespucci (1451–1512). Vespucci made at least two voyages to the New World, one in 1499–1500 and another in 1501–02. He is alleged to have made two others, one before and one after the known voyages, but evidence for his participation in those expeditions is lacking. In a letter dated 4 September 1504, published the following year, Vespucci was the first to claim that new continents had been discovered, and in the letter he coined the term Mundus Novus (New World). The published letter was widely read throughout Europe.

While Vespucci, or any other European for that matter, cannot be truly said to have “discovered” America (after all, the Indigenous people of the land were already there), he was the first European to have recognized the significance of Columbus’s “discovery.” So the naming of the continents after him is apt.

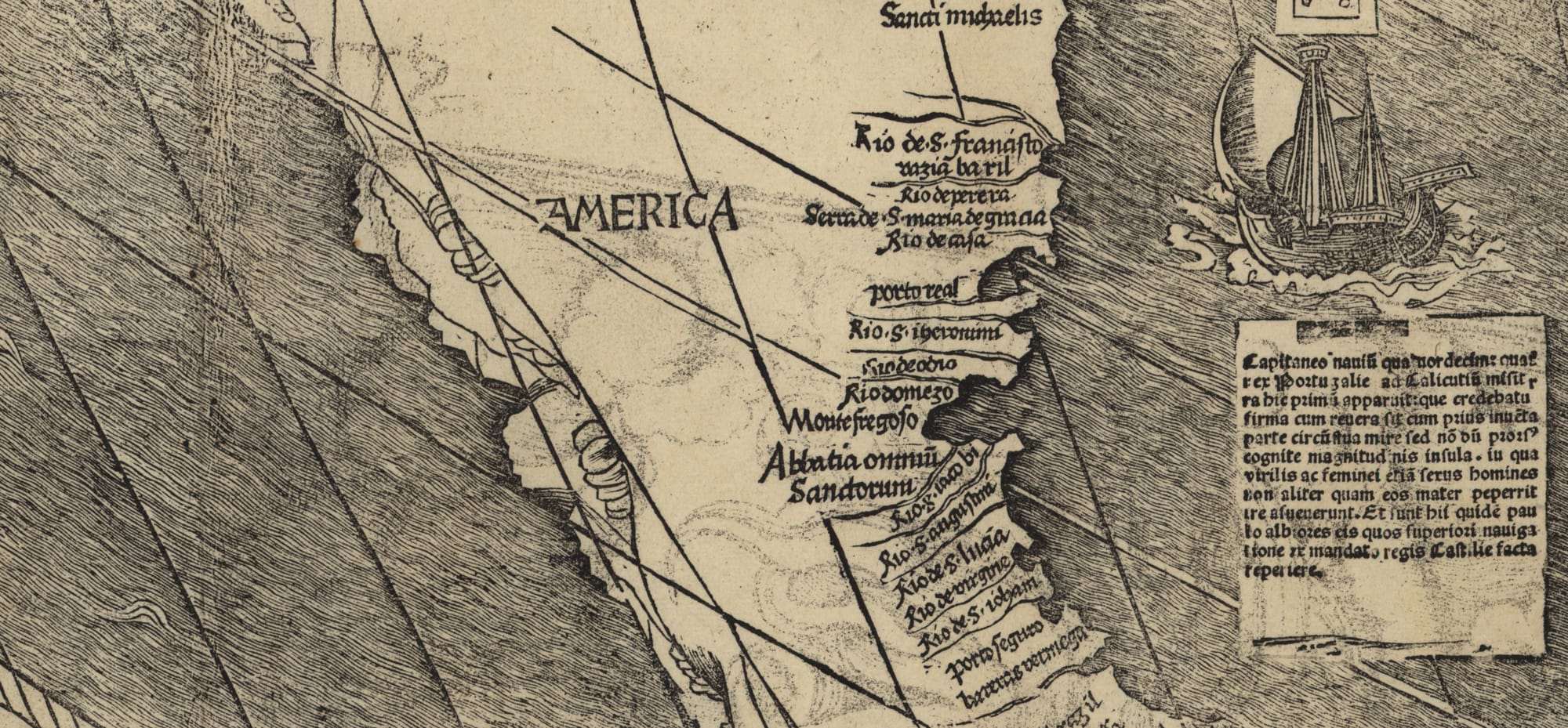

Cartographer Martin Waldseemüller was the first to apply the name America to the New World, specifically to what is now the continent of South America on the world map that accompanied his 1507 Cosmographiae introduction (Introduction to Cosmography). In that book Waldseemüller, or perhaps his collaborator Matthias Ringmann, justified the name and feminine form of America:

Nuc vo & he partes sunt latius lustratae /& alia quarta pars per Americu[m] Vesputiu[m] (ut in seqentibus audietur) inuenta est/qua non video cur quis iure vetet ab Americo inuentore sagacis ingenn viro Amerigen quasi Americi terra[m] / siue Americam dicenda[m]:cu & Europa & Asia a mulieribus sua for tita sint nomina.

(Now, these parts of the earth have been more extensively explored and a fourth part has been discovered by Amerigo Vespucci (as will be set forth in the following). Whereas both Europe and Asia received their names from women, I see no reason why anyone should justly object to calling this part America, as the land of Amerigo, after Amerigo, its discoverer, a man of great ability.)

Geradus Mercator was the first two apply the name America to what is now known as North America.

The name was in English usage by 1520, as evidenced by John Rastell’s poem A New Interlude of the year:

This sayde north p[ar]te is callyd europa

And this south p[ar]te callyd affrica

This eest p[ar]te is callyd ynde

But this newe land [i]s founde lately

Ben callyd america by cause only

Americus dyd furst them fynde.

The naming of America after Vespucci is widely accepted, but that has not stopped others from claiming alternative origins. These, however, uniformly lack any solid evidence.

There is a claim, promulgated in the twentieth century, that America is actually named after a fifteenth-century Bristol merchant named Richard Ameryk, who had some tenuous and vague connection with Cabot’s voyages of exploration (exactly what role he played is not known, but it was probably minor and connected with financing the voyages). While Ameryk did exist, the only evidence connecting him to the New World is a copy of the fifteenth century manuscript that says the continent was named for him. But the original manuscript was destroyed in an 1860 fire, and the passage in the copy is almost certainly a nineteenth-century interpolation. Fisherman from Bristol and other English ports did fish on the Grand Banks in the fifteenth century, prior to Columbus’s voyage, and it is plausible, and even likely, that they set up temporary camps on the coast of North America, but there is no evidence of them naming the place or otherwise recognizing it as a significant discovery.

Another alternative origin, more plausible than the Ameryk one but still lacking evidence, is that the name America derives from the Amerrisque mountain range in Nicaragua. This hypothesis has been circulating since the late nineteenth century. Amerrisque translates to “country of the wind” in Mayan, and the range is probably named for an Indigenous tribe of that name who once lived in the region. But no evidence from the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries of the existence of the name of the range, and the name could come from America, rather than vice versa, or the form of the name may have been altered under the influence of the term America. Any similarity between the Mayan name and America is almost certainly coincidence. The probability that some Indigenous term somewhere would resemble America is close to 100 percent, and this one would seem to be it.

Sources:

Everett-Heath, John. Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Place Names, sixth ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2020, s.v. America. Oxfordreference.com.

Hurlbut, George C. “The Origin of the Name ‘America.’” Journal of the American Geographical Society of New York, 20, 1888, 183–96. JSTOR. DOI: 10.2307/196759.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2002, s.v. America, n., American, n. and adj.; September 2003, s.v. New World, n. and adj.

Rastell, John. A New Iuterlude. London: 1520, sig. C.iii. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Waldseemüller, Martin. Cosmographiae introductio. Joseph Fischer, Franz von Wieser and Charles George Herbermann, eds. New York: United States Catholic Historical Society, 1907, 30. Gale Primary Sources: Sabin Americana.

Image credit: Waldseemüller, Martin. Universalis cosmographia secundum Ptholomaei traditionem et Americi Vespucii aliorumque lustrationes. Strasbourg, France?: 1507. Library of Congress. Public domain image.